Tucsonans in the early 1900s thought Sentinel Peak belonged to all of them — especially after University of Arizona students painted it with a giant white “A” in 1916.

Then a local real estate man and his wife acquired the land with plans to build a subdivision on it.

James R. "Jim" Dodson, who was born in Missouri in 1883, was the youngest of six children born to Benjamin C. and Maggie (Linder) Dodson, on Sept. 17, 1883 near Kirksville, Benton Township, Missouri.

By 1910, Jim and his brother John were salesmen for a medical implement company in or near Oakland, California.

On Dec. 23, 1917, Jim Dodson married Christine Gaustad, likely in Oakland, and a couple of years later they had their only child, Fernell. By 1918, Dodson was living in the Menlo Park area of Tucson and working in real estate with an office on Congress Street. Around this time he started considering the possibilities of a subdivision on Sentinel Peak, then just starting to be known as "A" Mountain.

Soon after, he met real estate agent F. O. Benedict and joined his new Benedict Realty Co., as secretary. The firm entered into an agreement with Benedict's old boss, H.E. Schwalen, and his Pima Realty Co., which controlled the Menlo Park development. Benedict Realty took over improvements and sales in the subdivision.

Around 1920, Dodson's brother Coston arrived in Tucson to work at Benedict Realty. Coston’s son Bob Dodson had traveled back and forth from California from as early as 1918 to assist Jim as a bookkeeper.

In 1922, Jim’s curiosity about the possibilities of Sentinel Peak turned to action when he filed a stone-and-timber claim — a cheap way to acquire land deemed unfit for farming — on 160 acres. The following year his wife filed her own claim on 40 acres, which included the "A" built by students of the university and completed in 1916. Both claims were approved by the state land office in 1924, and much of "A" Mountain fell into the hands of private owners — although almost no Tucsonans knew it. In the end, the couple owned 200 of the 272 acres that comprise the current Sentinel Peak Park.

The deal likely would never have been widely known but for a chance meeting between University of Arizona Professor G.E.P. Smith and a Mr. Murphy of the United States General Land Office. Within days of the meeting, at the San Carlos Hotel in Casa Grande, Smith had informed pioneer George J. Roskruge (namesake of Roskruge School) and word soon spread.

At the time, with Tucson facing the loss of one of its most important landmarks, many pioneers began to reminisce about its history and importance. Mose Drachman, who was born in Tucson in 1870 and became one of its leading citizens, recalled hearing tales of the days when Sentinel Peak — sometimes referred to as Picket Post Butte — served as a natural watch tower where townsfolk kept watch against Apache Indian raids. He also remembered what he called “the old stone fort” that still stood at the top of Sentinel Peak when he was a boy.

The “fort,” likely small fortifications used for lookouts, was also called sentinel station and was built in Tucson’s early days. The name Sentinel Peak comes from the sentinel station and the sentinel stationed there. During the U.S. Civil War, soldiers were posted at the sentinel station to warn of approaching enemies. A canvas stretched over the top to keep the sun off.

By 1883, only remains of the sentinel station existed. A circular wall, about 3 feet thick and made of boulders, enclosed an area about 8 feet in diameter. North of the circular structure was a small wall, roughly two feet high and about 10 feet long. To the east were traces of another, smaller circular wall.

As time passed, outrage over the Dodson’s land deal grew. Pioneers pushed civic organizations such as the Tucson Chamber of Commerce, University of Arizona, Women's Club of Tucson and the Tucson Kiwanis Club to action. They asked the General Land Office that ownership of Sentinel Peak be turned over to the City of Tucson. They argued that the mountain belonged to Tucson, but legally they had no ground to stand on. In 1872, when the Village of Tucson was surveyed by S.W. Foreman, its boundaries didn't include Sentinel Peak; ownership was left to the federal government.

On Jan. 16, 1925, the Register and the Receiver of the U.S. Land Office in Phoenix determined that the civic organizations had no legal claim against the Dodsons for ownership of a large part of Sentinel Peak, which the city wanted to turn into a large park. After the decision, Dodson's attorney said the couple was willing to donate 20 acres they had obtained under the Timber and Stone Act for a city park. This was in addition to 5 acres they had offered the university for land covered by the large "A".

In reaction to the adverse decision by the U.S. General Land Office, many civic groups petitioned the Mayor and City Council to appeal to the U.S. Land Office of the U.S. Department of the Interior.

To complicate legal matters, attorney Ben C. Hill, who had represented Dodson for many years, also was Tucson’s City Attorney. Due to the conflict of interest, the city retained Phoenix land attorneys John H. Page & Co.

In March 1925, Mayor John E. White signed a document saying the Dodsons’ claim was improperly made, and his homestead entry should be annulled. But legal proceedings didn’t take place until Oct. 9.

Four months later, a newspaper report said that "Dodson is absent from the city and his whereabouts are unknown...," It was learned later that he was in California.

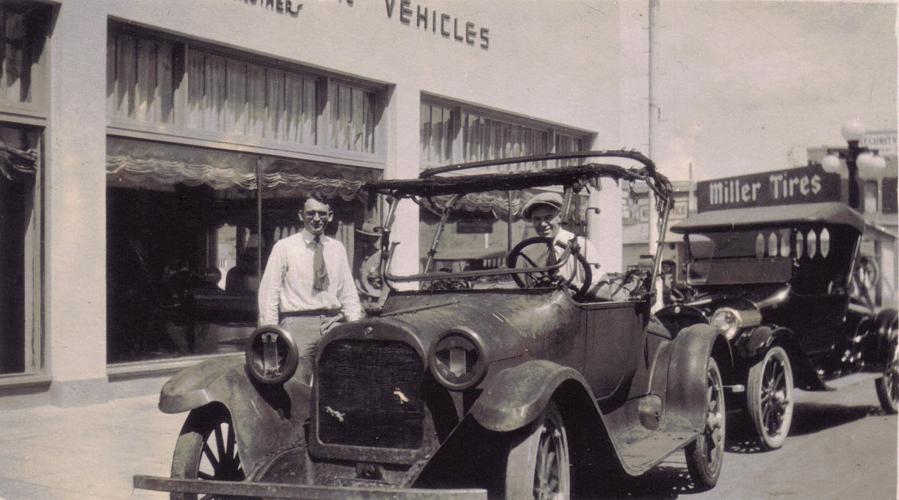

On Aug. 22, 1925, Dodson — along with his nephew Bob and fellow real estate agent Russell E. Cloud — were in front of the Benedict Realty Co. office at 136 E. Congress St. Suddenly a car pulled up and Alfred S. Shackleford, Dodson's neighbor and former friend, jumped out. Dodson and Cloud ran inside, chased by Shackelford, who unloaded three bullets into Dodson’s head and body. Shackleford then turned himself into the police, admitting he had shot, "that guy Dodson, the man who broke up my home."

The Dodson murder was reported to have been related to an alleged affair he had with Shackleford’s wife, Agnes. The sensational case was the talk of Tucson and drew huge crowds in the courtroom. During the court proceedings, the prosecution and defense presented a mountain of conflicting evidence. Had an affair taken place? If so, did Dodson or Agnes Shackleford instigate it — and if it was at Dodson's idea, as the Shacklefords said, why did he take out insurance with Agnes as the beneficiary? Was Shackleford temporarily insane when he murdered Dodson? Or, although the question was never asked during the trial, had someone else orchestrated a murder plot to eliminate Dodson from the Sentinel Peak court case, which was to begin soon?

In the end, the defense convinced the jury that Shackleford had suffered extreme mental suffering due to Dodson's affair with his wife. He was found not guilty. The Shacklefords walked out of the courtroom arm in arm, amid applause from the audience in the courtroom. The insurance money, which amounted to $7,500, was given to Dodson's wife instead of Agnes Shackleford.

On Oct. 8, 1925, with the Shackleford case still in session, and the day before the first of two hearings with the land office, land attorney D.B. Morgan said, "The city has but to prove that Sentinel Peak has been in use as a public recreational ground in order to have the claim of the Dodsons...cancelled."

The following day, he did that and more, telling of the "ancient Indian fortification on Sentinel Peak" and of Sentinel Peak’s "general use by university students, children and citizens."

"We made an examination of the peak today and can observe the fortifications are still there. The policy of the government in the past has been to withhold from private owners, historic monuments such as those fortifications,” he said. "The law has been repeatedly construed by the Secretary of the Interior and it has been uniformly held that the land must be unoccupied before a timber and stone filing will be allowed, and the department has gone so far as to hold that even where the occupancy operates as a trespass against the government, that fact is immaterial."

As the case continued, numerous pioneers testified that “A” Mountain had long been used for family picnics, sunset religious services and enjoying the city views. Herbert Drachman (namesake of Herbert Avenue), who was born in Tucson in 1876, remembered Sentinel Peak "as a place where kids played," and of "the old graves that had been located there."

City attorneys also showed that the rock was not valuable for building, as Dodson had asserted. They argued that his real intention was to build a subdivision. David S. Cochran, a builder for 29 years in town, testified that, "...the peak was not valuable for its rock, as "crushed rock could be obtained easier and cheaper at the quarry." Frank H. Hereford said he was a part owner of the Welch quarry at the base of “A” Mountain, which proved a failure since there wasn't enough demand for rock to support two quarries.

Also at the trial, A.M Franklin testified of the city’s interest in 1905 to build a hotel on top of the mountain because of "its commanding site and majestic view." University of Arizona football coach J.F. "Pop" McKale (namesake of McKale Center) said no university athletic events had taken place on the mountain but did talk of the annual university "A" Day celebrations.

By July 1926, both land claims had been voided by the Commissioner of the General Land Office with the final option to appeal to the Secretary of the Interior. The following February, the Secretary of the Interior upheld the decision and the two claims comprising 200 acres of Sentinel Peak and land around it were void forever, although it doesn't appear the city got the land until late 1928.

By 1929, talk of building a road to the top of “A” Mountain was becoming common as this was one of the federal government’s stipulations for the city to keep the 200 acres. The following year, a survey was done for Sentinel Peak Road, likely following a dirt path up the mountain that had been there since at least the late 1800s.

In 1931, Solot & Dowling, a real estate firm that at that point owned the very top of “A” Mountain, offered to give that piece of land to the city as an incentive to build the road. That may have been the impetus that got the heavy graders rolling.

In 1933, with the road built and the park in the hands of the people of Tucson, a ceremony was held and an historic marker, donated by the Daughter of the American Revolution, was placed on Sentinel Peak. UA President Byron Cummings spoke to the crowd of several hundred.

"On this lofty outlook we get a perspective which is missed by most men in the valley below,” he said. “Upon it have stood the best of men of the generations that have gone. From it, have sounded the messages of good cheer and warnings of danger through the centuries. It is fitting that we place here our offering to their memory, a monument to the preservation of the home."