In 1920, a small sanitarium was opened for tuberculosis patients in an old saloon and dance hall at Pastime Park. It was the precursor to the Veterans Hospital we now have in Tucson.

The Star ran a story about it's beginnings as the VA marked an anniversary.

From the Arizona Daily Star, July 24, 1960:

It's Come a Long Way Since 1920

VA Hospital Marks Birthday

After World War I

TB Filled Wards

By DON ROBINSON

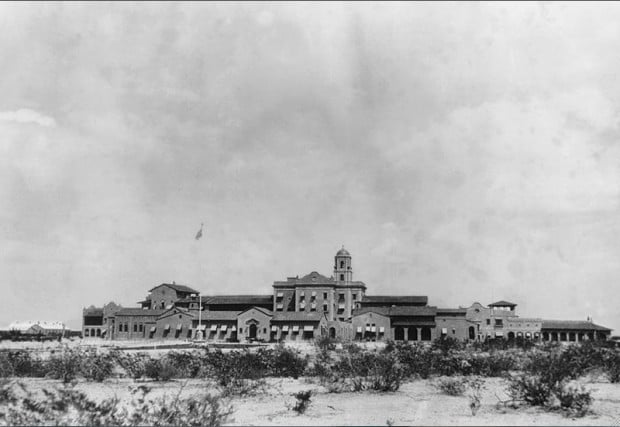

Large bronze plaques on either side of the main entrance identify the place as a U.S. Veterans Hospital.

Beyond the perpetually open wrought-iron gates stretches a narrow drive flanked by huge palm trees and carpet-like lawns.

At the end of the drive, stucco, pink-tinted. Spanish-style buildings seem to sprawl in all directions through tree-shaded grounds. It's more like the approach to a swank resort than to a hospital.

Parking your car, you walk up the steps of the administration building, through the lobby, then out into a huge patio trimmed with flower beds and edged by concrete walks.

Along the right side of the patio are the kitchens, dietary offices and a spacious dining room filled with white-clothed tables where ambulatory patients, visitors and staff have their meals.

On the opposite side of the patio is a well-stocked, cheerfully decorated canteen complete with fountain and sandwich grill. Further on is a large auditorium with a curtain-draped stage.

Next to the auditorium is an 8,000-volume library with books that range from Zane Grey to Dickens. You can read the latest mail edition of The New York Times or the Christian Science Monitor. Magazines run from pulp detective to Harpers Weekly.

On past all of these are the somehow forbidding wooden doors of the main building. Inside, a white-jacketed nurse's aide brushes by pushing a seemingly disinterested, green-jacketed patient on some routine laboratory mission.

Drab colored halls reach out on either side of the lobby and the three floors above it. In the pale green rooms men with bored and frustrated expressions of hospital patients the world over lie in high beds. They read, talk, stare blankly at the walls and ceiling, tell stories of a fabulous and healthy past, or just sleep.

The sunlight, the green lawns, the palm trees and flowers, seem miles away.

Dropping into rooms along one of the T.B. wards you visit briefly with the patients. "The chow is good," a middle-aged veteran of World War II said. "It gets tiresome like anywhere else. But it's good."

Across the room a gray-haired veteran of the Argonne grinned wisely. "A feller's apt to complain about the chow soon's he gets the wrinkles out of his belly."

Moving along you ask more questions, and learn that movies are shown regularly on the wards. A library cart and a small mobile canteen make scheduled visits to each room. More than 300 volunteer workers from 28 orgainzations provide everything from free cigarettes and candy to entertainment and occupational therapy.

A man who had been in and out of Veterans Hospitals more times than he can remember in the last 30 years looked back on his TB-plagued life and remarked: "I don't know what the hell we would have done if they didn't have places like this."

There was a time when there were no places like this.

Old timers in Tucson can remember the pathetic hundreds of coughing, blood-spitting victims of German gas, cold muddy trenches and unfortunate trysts with pretty but tubercular French girls who poured into Tucson after World War I.

A shocked population watched them come and for a while helplessly watched them die, because it takes a lot more than the hot dry climate they had sought to cure TB. It takes rest, security and good medical attention.

And the people of Tucson were not loing in coming to the aid of their over-burdened climate in these respects.

Led by the late Dr. Neal D. McArtan, himself a tubercular, the Chamber of Commerce, the Red Cross and veterans orgainzations, enough attention was focused on the problem so that in 1920 the Public Health Service opened a small sanitarium in an old saloon and dance hall at Pastime Park. The dance hall was converted into a ward, the bar was turned into a kitchen and mess. Overflow patients were put into tents.

There were more than 200 patients. The overworked staff consisted of Dr. McArtan, three nurses and three administrative assistants.

Along with the fighting spirit of the place there was the glorious legend that somewhere beneath the dusty grounds old Charlie Loeb, former owner of the saloon, had buried his stock of liquors when prohibition had seemed near in 1916.

Charlie was killed by two hold-up men for 80 cents in 1917. And he had never told anyhone where all that booze was buried. If an enterprising patient ever discovered the magnificent mother-lode, he kept it to himself.

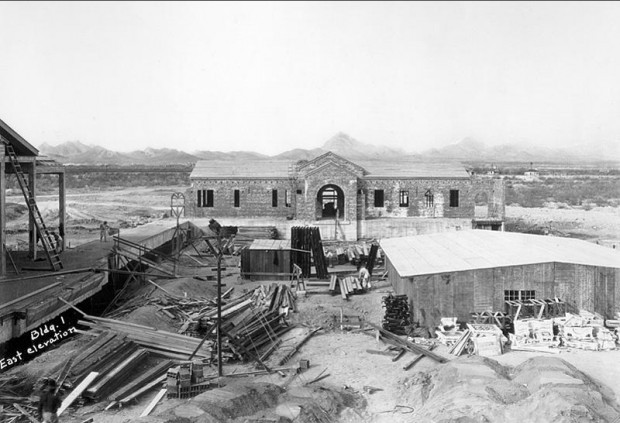

On May 1, 1922, Pastime Park was taken over by a recently formed Veterans Bureau. More doctors and other personnel were assigned. Fifty four-man cottages were built to take the place of the tents. But it still was rather crude.

Judge Lee Garrett, who was a patient at Pastime Park from the fall of 1921 until mid-summer 1927, remembers vividly his life there.

"The buildings were all wood frame," Judge Garrett said. "They had screened sides with canvas flaps that could be lowered during dust and rain storms. We had little pot-bellied coal heaters and we built and kept up the fires ourselves. There was a big latrine out back and it wasn't a pleasant trip late at night or when it was rainy or cold."

The judge remembers that the food was good and that the staff was dedicated. "We had a library, movies and a rehabilitation program."

He can name many of today's prominent citizens in Tucson and elsewhere who once "battled the bug" in Pastime Park.

Pastime Park grew from three to 86 buildings in its 9 1/2 years of existence. A total of 3,583 veterans of World War I, the Spanish American and Civil Wars were admitted.

Then in 1928 the present hospital on S. 6th Ave. was formally opened. The patients still were mostly tuberculars.

In 1930 the Veterans Bureau was changed to the Veterans Administration. Gigantic research programs were begun. New drugs were developed.

Last week the hospital announced that of its 400 beds, the number assigned to TB patients had dropped from 234 in 1956 to only 90. It is estimated that eight times the number of TB patients can be treated with the same number of beds as before.

Today the hospital's staff comes to about 500 persons, including 21 doctors and three dentists. Another 28 doctors are available on a consultant basis.

Of course, the "today" that reporter mentions happened in 1960.

According to the website of the Southern Arizona VA Health Care System at www.tucson.va.gov , it now serves more than 170,000 veterans in eight counties in Southern Arizona. The hospital has 285 beds. It employes more than 2,100 health-care professionals and support staff.