It’s alive!

The first paper published on the scientific results from July’s flyby of Pluto concludes that a variety of atmospheric and geological processes continue to reshape the planet — 4.5 billion years after its birth.

“Pluto’s engine is still running,” said Alan Stern, the Southwest Research Institute scientist who conceived and led NASA’s New Horizons mission to Pluto.

The paper, published today in the journal Science, reports that “some of the processes operating on Pluto appear to have operated geologically recently.”

“This raises questions of how such processes were powered so long after the formation of the Pluto system.”

The source of Pluto’s reshaping, evidenced in its plains of frozen ices and towering ice mountains, is a mystery awaiting solution.

More questions — and some answers — will come from data still aboard New Horizons, now 70 million miles beyond Pluto and headed toward other targets in the vast Kuiper Belt of icy comets and dwarf planets beyond Neptune.

New Horizons data, saved on two hard drives with less storage than the phone you have in your pocket, is dribbling results back to Earth at speeds lower than your home computer connection.

Stern, reached by phone at the Minneapolis airport Tuesday, said 85 percent of the data gathered on the flyby has yet to be transmitted to Earth.

Some things will remain a mystery. There is just not enough data in this one brief flyby to make conclusions about what lies beneath Pluto’s surface.

Stern said the data will answer some of the questions raised in this initial paper. “All the best spectroscopy and high-resolution mapping data, that’s still up there and will shed of lot of light.”

It should all be in hand by this time next year, he said, and analysis of it by planetary scientists will no doubt raise even more questions.

“When we get done, there will be people clamoring for an orbiter to Pluto. I may be one of them,” Stern said.

Some of the article’s conclusions have already been overshadowed by more recent revelations from NASA. The paper infers, for example, that Pluto’s mountains, rising to 11,000 feet, are water ice, hardened to rocklike permanence in the dim sunlight and freezing temperatures.

Last week, NASA announced that spectrographic data had identified water ice in some of the planet’s mountainous regions. Inference is no longer needed.

But that still leaves the question of what is pushing them up from the surface of the planet.

“We still don’t understand it all, I’m afraid, and that’s fantastic,” said Veronica Bray of the University of Arizona Lunar and Planetary Laboratory.

“It’s really nice to have a couple of big questions to be scratching our heads about,” said Bray, whose expertise is in comparative planetary surfaces. She is one of more than 150 authors of the Science paper.

The biggest question is related to the surprising surface features of the dwarf planet. Most scientists had expected Pluto to be something of a frozen wasteland of rock and ice, pocked by craters — more lunar in appearance than planetary.

It has, after all, been a sitting duck for 4.5 billion years in a belt crowded with billions of other icy rocks.

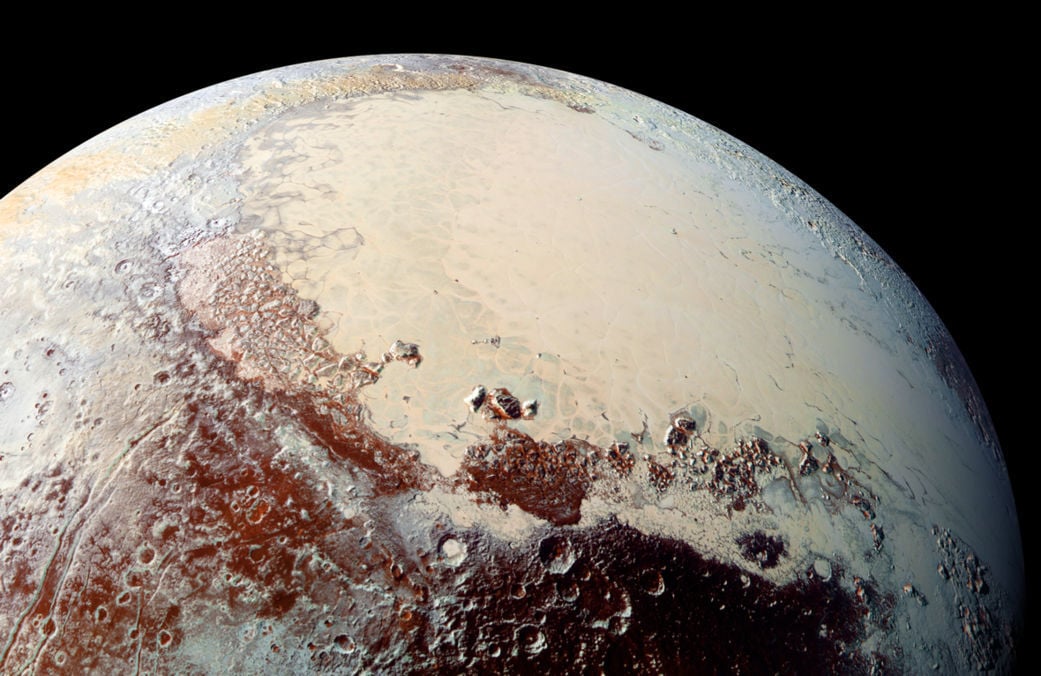

Instead, the New Horizons flyby revealed regions of smooth plains and ice mountains where any evidence of bombardment has been erased — pointing to recent geological and atmospheric activity.

The signature surface feature of the face of Pluto is that white, heart-shaped plain that the team tentatively named Tombaugh Regio, in honor of Clyde Tombaugh, the Lowell Observatory astronomer who discovered the planet in 1930. It, and the mountains that border it, require some reshaping force, the paper notes:

“For Pluto, the rugged mountains and undulating terrain in and around TR (Tombaugh regio) require geological processes to have deformed and disrupted Pluto’s water ice–rich bedrock.

“Some of the processes operating on Pluto appear to have operated geologically recently, including those that involve the water ice–rich bedrock as well as the more volatile, and presumably more easily mobilized, ices of SP (Sputnik planum) and elsewhere. This raises questions of how such processes were powered so long after the formation of the Pluto system.

“The New Horizons encounter with the Pluto system revealed a wide variety of geological activity — broadly taken to include glaciological and surface-atmosphere interactions as well as impact, tectonic, cryovolcanic and mass-wasting processes — on both the planet and its large satellite Charon.”

This is where the head scratching comes in.

What is driving that geological activity?

On Earth, we know the answer. Decay of radioactive materials in its core supplies the energy. Pluto, with a mass that is 0.2 percent of Earth’s, should have lost its radioactive heat by now, said Bray.

Will Grundy of Lowell Observatory said Pluto has enough rock to retain radioactivity from the decay of elements such as uranium and thorium.

“The amount of heat you get is puny, but it’s not zero,” he said.

Grundy, who heads the surface composition team for New Horizons, said it doesn’t take much heat to account for the glacial motion of the abundant frozen gases — methane, nitrogen and carbon monoxide — on Pluto’s surface.

Those gases don’t exist in frozen state on Earth, but on Pluto, with a surface temperature of minus-375 degrees Fahrenheit, they cover much of the planet.

“All of these complicated mixed ices have material properties we don’t yet understand,” said Grundy. “They essentially make alloys. Their behavior depends on their thermal history, and they have a huge richness of mechanical and material properties.”

Grundy has worked with such frozen gases on a small scale for much of his career. He said he made his first laboratory batch of methane ice while studying at the UA’s Lunar and Planetary Lab in 1988.

More recently, he has worked with colleagues at Northern Arizona University to grow ices in the compositions he knew he would encounter on Pluto.

He is now awaiting the stored spectroscopy data from New Horizons for comparison.

Revelations await, he said.

“That tiny, tiny little taste we got in this first paper is like the hors d’oeuvres at dinner. It shows you what the kitchen is capable of and gets your salivary glands going.”

Mark Sykes, one of four unaffiliated “referees” of the Science paper, said his review of these first results confirmed his amazement at what is being discovered.

“It just never ceases to amaze me, when I look at this stuff, how dynamic Pluto and Charon are. It has dunes, for crying out loud, dunes, and these mountains and glaciation.

“The main takeaway is that Pluto is an active world. It’s got energy in its interior, which is driving geology to its surface today — not 4 billion years ago — today.”

Sykes, director and CEO of the Tucson-based Planetary Science Institute, said the paper contains “far more questions than you get answers. But the range of geology that this paper reveals is beyond surprising.”