Bashar Rizk doesn’t just suspect we will find life on Jupiter’s moon Europa; he’s certain it’s the best place in the solar system to look for it.

“I think there is a better than even chance there is life on Europa,” he said.

Rizk, a senior staff scientist at the University of Arizona’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, leads a team proposing a suite of cameras for a NASA mission to help discover whether life might have developed in the liquid ocean beneath Europa’s frozen crust.

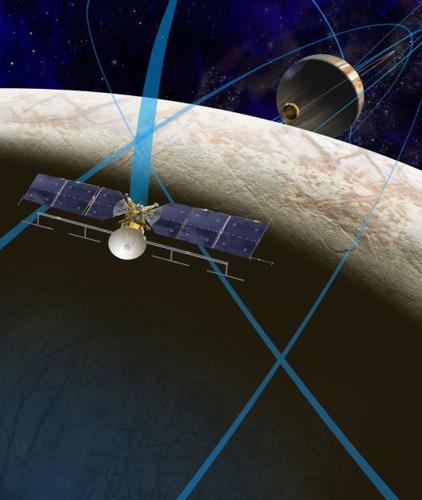

For years, the accepted theory was that the ocean was buried under impenetrable ice. Now most planetary scientists agree that it contains fractures where that water meets the atmosphere.

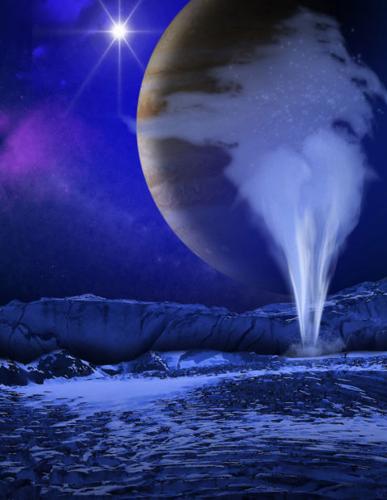

Four teams from the Lunar and Planetary Lab are vying to build instruments for a Europa Clipper, proposed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, or for some variation of that mission.

Startup funds for the project are contained in NASA’s proposed budget for next year — a $30 million down payment on what could be a $2 billion mission.

Richard Greenberg, who is on the science team for Rizk’s camera proposal, first made the case for a connection between Europa’s ocean and its atmosphere 18 years ago.

Greenberg, a professor in the UA Department of Planetary Sciences, was on the imaging team for NASA’s Galileo mission to Jupiter’s moons. He and his students theorized that Europa’s surface features provided evidence of surface contact.

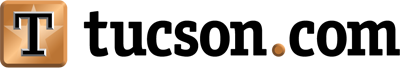

He said the current buzz about Europa, heated by the announcement in 2013 that the Hubble Space Telescope saw evidence of erupting water geysers at Europa’s south pole, is “exciting. My book sales have just jumped up.”

Greenberg wrote two books about Europa, including one for the general public in 2008, called “Unmasking Europa: The Search for Life on Jupiter’s Ocean Moon.”

For years, the “thick-ice people” dominated the discussion. “The thick-ice people said it was greater than 20 kilometers. People are now settling on 5 to 7 kilometers,” he said. (A kilometer is about two-thirds of a mile.)

The ice is “permeable,” he said, with plenty of chaotic terrain and features that look like earthquake faults, with double ridges of refrozen slushy material that have always indicated to him a connection.

Europa is far from the sun — five times Earth’s distance — but it is heated by the tremendous tidal influence of Jupiter, which is 300 times more massive than Earth.

Liquid water, a connection to a surface seeded by asteroids and comets with the building blocks of life, and possible thermal venting at its rocky undersea core could supply all the ingredients needed for biogenesis.

Timothy Swindle, director of the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, said LPL scientists are proposing a variety of cameras for whatever mission is mounted.

He said Alfred McEwen, who heads up the HiRISE camera team that has been mapping the surface of Mars from NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, has two proposals.

One is a camera for a Europa mission, in conjunction with a colleague at Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Lab — UA alumna Elizabeth Turtle. The other is a Discovery mission to Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io that could also image Europa from its orbit around Jupiter.

The Europa Clipper proposal orbits Jupiter rather than Europa to keep the spacecraft out of the intense radiation environment created by the giant planet’s electromagnetic field.

Walter Harris, a UA associate professor of planetary atmospheres, is proposing a camera that will do its work when the spacecraft is far away from that crazy radiation.

He is working with JPL on an ultraviolet imaging spectrometer that would focus exclusively on finding hydrogen and oxygen, evidence of water escaping from Europa.

His camera would begin working long before the close approach, he said — ensuring that at least some data are gathered.

“The environment is bad enough that you never know what’s going to happen to your spacecraft,” he said.

It could observe from 1 million to 3 million kilometers out, as the spacecraft inserts into an orbit, Harris said.

If his instrument sees evidence of plumes, the cameras designed to observe close-ups with greater resolution can target those areas.

It’s not unusual for LPL to submit numerous proposals, some of which appear to be competitive, Director Swindle said.

“In the early part of the last decade, there was a call for ideas for Mars proposals. Of the 10 selected for further study, Peter Smith’s name was on half of them.”

Smith ended up being the lead on NASA’s Phoenix Mars Lander, the first NASA mission run by the University of Arizona.

LPL is now preparing to lead its second NASA mission.

OSIRIS-REx, scheduled to launch in September of 2016, will attempt to collect a sample of pristine asteroid material and return it to Earth.

Rizk’s cameras for that mission are the prototype for his Europa proposal.

OSIRIS-REx will have a low-, medium- and high-resolution camera on board.

For Europa, Rizk and his team are proposing one high-resolution camera, capable of zooming in on areas identified by two lower-resolution cameras that would map Europa’s surface in stereo, providing depth to the image, similar to the way human eyes operate in tandem.

“That gives us a stereo capability to understand the topography and geological history,” Rizk said.