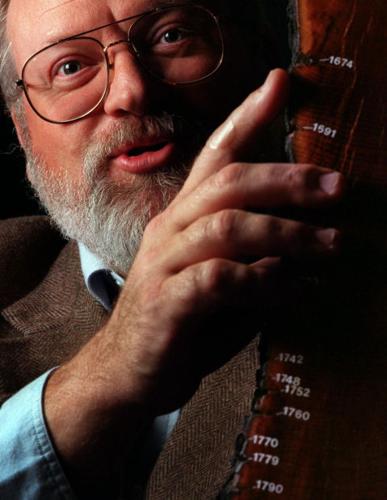

Tom Swetnam grew up among the trees he would later study intently.

Swetnam roamed the national forests of New Mexico as a child, living in Jemez Springs where his father, Fred, was the district ranger for that part of the Santa Fe National Forest.

After earning an undergraduate degree in biology and chemistry from the University of New Mexico, Swetnam worked as a seasonal firefighter in the Gila Wilderness of western New Mexico on a helicopter team that got dropped into burning forest for initial attack.

In those days and in that place, it was usually pretty calm.

“We’d end up landing on some ridge in the middle of nowhere. There would be one tree burning. First thing we’d do is get out the coffee pot.”

The crew would then secure the site to make sure the fire couldn’t grow, then hike on out, sometimes over 30 miles of trail-less wilderness.

It seems an unlikely beginning for an academic researcher, but Swetnam parlayed his wilderness skills into a Ph.D. and a career at the University of Arizona that led to directorship of a renowned research lab, appointments as Regents’ Professor and, most recently, as a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

He gained a reputation as the go-to guy for historical reconstruction of fire history in forests from the Southwest to Siberia.

“He is one of the premier dendroecologists in the world,” said Steve Leavitt, who took over as acting director of UA’s Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research when Swetnam submitted his resignation as director in the fall.

The College of Science is searching for Swetnam’s successor and he and his wife, Suzanne, have moved to a home in the forests of New Mexico, not far from where he grew up.

an outdoor education

Swetnam was still working summers for the Forest Service when he was picked to accompany a scientist from the Rocky Mountain Research Station on a 10-day pack trip in the Gila.

The researcher, Jack Dieterich, told him he should go study tree rings and do a fire history of the Gila.

He enrolled in the doctoral program at UA and spent much of his graduate program back in the Gila, doing just that.

His wilderness skills aided his research. He felled trees and cut sections with a crosscut saw. He packed samples out by mule.

Fire histories became a “cottage industry” for him, he said.

“There was some tree-ring work done on reconstructing the history of fire in the northern Rockies. It hadn’t been really systematically approached and nobody had worked on the climate aspect of fire — not much anyhow.”

His fire history of the Gila, done with Dieterich, became his master’s thesis. “By the time I finished my Ph.D., I had done 15-to-20 studies.”

Malcolm Hughes was director of the tree-ring lab back then. He said Swetnam was “a pain in the neck for us” — administratively.

“He had this vision of putting together the history of fire in the Southwest and there wasn’t an easy, single source of funding for it and Tom managed to put together a whole set of $5,000 funding from various national forests and parks.”

Overall, Swetnam’s arrival at the lab was a plus, said Hughes.

“Here’s this very smart guy, way smarter than he cracked on to anybody, with very good technical and analytical skills. On the other hand, he was very much a son of the Southwest.”

Physically imposing and soft-spoken, Swetnam related easily to the forest and park rangers he dealt with in the field, said Hughes.

“Within minutes Tom would have them eating out of his hand,” he said.

“His talent was both who he was and the fact that he had this big question, this big picture. That’s the fertile ground from which all of his work grew.

“It was a wonderful example of real science done out of curiosity, but of enormous value to society.”

a changing landscape

What Swetnam documented in his studies of fire scars in the Gila and elsewhere was that smaller and less frequent fires were the norm after “settlement” in the early 1900s.

A paper he and Dieterich presented in 1983 listed three factors for the dearth of ground-clearing fires in the ponderosa pine forests of the Gila — relocation of the native populations, grazing of sheep and cattle, and fire suppression.

The Gila became the nation’s first officially designated wilderness in 1924, and its managers were beginning to reintroduce a more historically normal fire regime when Swetnam studied the area in the 1980s. “The Gila was really progressive in understanding that fire is a natural part of the ecosystem,” Swetnam said.

He became a proponent of returning landscape-scale fire to the forests — a philosophy now embraced by most forest managers. It remains a difficult thing to enact — mainly because of fear those fires will spread to developed areas within or bordering the forests.

They call such places the Wildland-Urban Interface, and Swetnam’s retirement home is now set within one.

“I guess I’ve become part of the problem,” he said recently in a phone interview from his cabin, on a ridge above San Diego Canyon near the Valles Caldera National Preserve.

The previous owner did a good job of making the home fire-safe and keeping the adjoining acreage thinned, but Swetnam has seen enough wildland fire to know there are no guarantees.

“I can make this place as good as can be and it may not matter if a fire starts a couple miles away and there is wind driving it,” he said.

Fire behavior has changed radically since Swetnam’s fire-fighting days. Since the mid 1980s, wind-driven blazes have decimated large swaths of drought-stressed Western forests.

The evidence is nearby. Stand-clearing fires ravaged some of Swetnam’s favorite places in the mountains of northern New Mexico in recent years — Cerro Grande in 2000 and Las Conchas in 2011.

A study he published in 2010 with A. Park Williams and other researchers concluded that 18 percent of the Southwest’s high-altitude forests had succumbed to insects, disease and fire, possibly for good.

Then came the wildfire year of 2011. Swetnam said the estimate is now over 20 percent.

The outlook is grim.

By 2050, the average measures of “forest drought stress” will be as extreme as those of the worst drought period of the past 1,000 years, Swetnam and other researchers concluded. The 2012 study was based on a 1,000-year history of climate, gleaned from a data set mostly compiled over the years by Swetnam, his students and his colleagues.

He is still an advocate of thinning and burning the forests, though he now recognizes that it won’t stop the ecosystem changes.

“We still need to have landscape fire, but that’s not going to save us from the warming. If we just let it rip, we’re going to lose too much of what’s valuable,” he said.

leaving his mark

Swetnam’s legacy at the University of Arizona is both physical and programmatic, said Hughes.

“Tom has presided over a number of major and positive shifts,” said Hughes, who handed the reins to Swetnam in 2000.

The most obvious shift is the lab’s new $12 million building. Swetnam guided that process through a time of severely limited budgets, securing a donation from the late Agnese Haury.

Another part of the legacy is personal. His son, Tyson, trained as a dendrochronologist. He recently earned his Ph.D. from the UA in natural resources and is working as a research scientist in geosciences.

“I don’t know if I really had a choice,” said Tyson. “I got to college and he was all over me about what I was going to do for my major. Fortunately, I liked ecology and wanted to do science.”

“Now that I’m a Ph.D. it’s like, ‘Hey, aren’t we going to do some projects together?’”

While they’ve had no official collaborations, their work has already overlapped. Tyson works with the UA’s Critical Zone Observatory, using remote sensing to uncover the effects of fire in the Jemez River Basin. This past summer, he uncovered what appeared to be ancient agricultural fields.

He told his father, who is working on a National Science Foundation project, to explore the connections between climate, fire and human habitation in the region.

“He went out and ground-truthed it,” Tyson said.

Tom Swetnam took some archaeologists out to the site and confirmed the presence of 400-year-old farm fields. “Have you seen Tyson’s images?” Swetnam asked. “They are really good.”

There will be more collaborations, Tom Swetnam said. He intends to retire his faculty position, but continue working with his colleagues and his son as an emeritus professor.

His decision to retire at age 59 after 14 years as director came partly in response to some new directions at the lab, he said, but was mostly triggered by his love of the land.

When he returned to New Mexico to do research on the NSF grant, he and his wife started looking for a home.

“I said ‘This is where I want to be.’”