A photo of a shipwreck, buried in silt for centuries and containing cargo in unbroken ceramic vessels, drew the only gasps at a recent seminar on the archaeology of the Mediterranean at the University of Arizona.

The archaeological dig at Yenikapi, a port and quarter in modern-day Istanbul, has been “a gold mine,” said dendroarchaeologist Charlotte Pearson. The ships are so well-preserved “you can smell the resin,” she said. The vessels, called “amphorae,” contain all manner of preserved cargo.

It wasn’t the cargo she coveted.

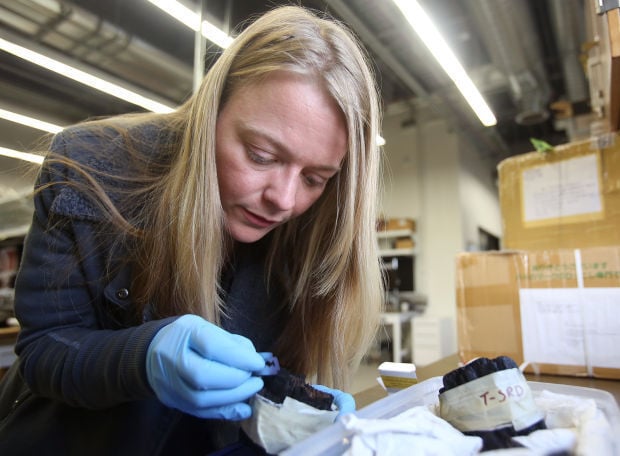

For Pearson, who combines training in geosciences, archaeology and tree-ring dating at the UA’s Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research, the real treasures uncovered in Istanbul at the “Lost Harbor of Constantinople” are the wooden ships themselves and the oak piles of the harbor’s piers.

Those piles are mostly ancient oaks, harvested from far-flung corners of the Byzantine Empire. They hold clues to patterns of trade and variations in climate in the 4th century A.D.

Pearson and colleagues have managed to collect nearly 4,000 wood samples from the site.

The samples are not from the vicinity of Istanbul — the Turkish capital previously known as Constantinople and Byzantium.

The tree rings in some of them match patterns found in wood from a fort on the Danube River. Constantinople, with ports on the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, was a city of 600,000 and the center of trade in the Old World when the harbor was built by Emperor Theodosius I.

When the emperor called for wood to build a new harbor, it came from everywhere. The samples present an opportunity to settle important dates in our understanding of classical history, Pearson said. They hold clues to climatic and geological events — droughts, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions.

“Tree rings give us climate on a scale that makes sense to people,” Pearson said. “In the Mediterranean, we have a massive history of people, and in all that time they’ve been doing things with wood.”

THE POWER OF TREE RINGS in archaeology

The chronology, made by matching overlapping patterns in tree rings found in widespread archaeological finds and ancient buildings, is a lifelong vision of Pearson’s mentor, Peter Ian Kuniholm.

The dig at Yenikapi, whose riches began to be uncovered when the Turkish government excavated a park in Istanbul in 2004 for a $5-billion rail-transit system, will help complete that vision.

Kuniholm, who holds an emeritus appointment at the tree-ring lab, was in Tucson last week to meet with his former colleagues from Cornell University, who moved to the UA three years ago.

Kuniholm studied classical archaeology after abandoning a career teaching English, but now dismisses the whole thing, humorously, as “pots and pans.” He finds the notion of using excavated pottery to date things by eras and periods to be impractically imprecise.

“It’s all a matter of aesthetics and taste and opinions, with not much visible means of support,” he said.

Historical texts are similarly deficient, he said.

Consider the Egyptian Pharaohs. Ancient texts give pretty good clues about when they reigned and for how long — enough to compile a high, low and middle chronology, with the middle being the average of the two outside estimates.

“FDR had three four-year terms as president; Jimmy Carter, one. Try to rewrite American history using that average,” he said. “It doesn’t work.”

Tree rings found in archaeological digs can more accurately date when something was built, he said.

In addition, the climate signatures found in tree-ring growth can help archaeologists match societal upheaval to climate and natural phenomena.

If you have a theory that links the collapse of civilizations to drought, Pearson said, “the tree rings can tell you, ‘When did it happen? How long did it last? And are we really seeing this at the same time?’”

FROM CORNELL TO THE UA

Kuniholm did most of his work at Cornell University, at what became the Malcolm and Carolyn Wiener Laboratory for Aegean and Near Eastern Dendrochronology. Over the years, he has supervised the work of “500 students and grand-students,” he said.

He has accumulated “about 7,500 years worth of chronology, but not in continuous sequence” for the eastern Mediterranean.

Until Yenikapi, it contained “a Roman gap — centuries on either side of the Year One,” he said. That gap is filling in.

The work of analyzing the wood is now being carried on at the UA tree-ring lab by former students and associates, such as Pearson and Tomasz Wazny, who relocated to the UA after Kuniholm left Cornell.

It wasn’t a great time for hiring, but the UA was adding office and lab space in its new tree-ring lab, and the Cornell researchers brought their Wiener Foundation money along with them.

Wazny is the hunter-gatherer of the group. He spends each summer motoring across Eastern Europe, gathering wood samples from ancient buildings and archaeological digs.

Steven Kuhn, who along with his wife, Mary Stiner, has been working digs in the Mediterranean region for 25 years, said the tree-ringers who relocated from Cornell now form part of a “huge mass of people interested in ancient climate, cultures and environments.”

Kuhn is director of the UA Center for Mediterranean Archaeology and the Environment, created to take advantage of that interest. The center itself is “mostly aspirational” at present, he said, but the collaborative research it is designed to foster is an ongoing reality.

Pearson is the center’s associate director. Also involved are researchers from the tree-ring lab, the College of Anthropology, the radiocarbon lab and the department of geosciences. Foundation head Malcolm Weiner is a center member.

hard sciences added to classics research now

Classical archaeology, the study of the cradles of civilization around the Mediterranean, was once ensconced at the UA in the classics department, but the archaeologists from classics were brought into the College of Anthropology seven years ago, Kuhn said.

Collaboration is a boon to important research, said noted archaeologist David Soren, one of those classical archaeologists.

“I think what’s happening is that, basically since the 1980s or so, there has been this revolution to incorporate hard science into fields that were traditionally peopled by classicists, people who studied Greek and Latin and went off into the field and wrote nice, esoteric things about it.”

“Now you really can’t be a ‘pots and pans’ person without recognizing the hard sciences.”

Soren, a Regents’ Professor of classics and anthropology, recognized that early in his career. He is credited with being the first archaeologist to use DNA sampling and analytics in his work — a collaboration that led to important theories about malaria and the collapse of the Roman Empire.

He still works on that theory and collaborates with Pearson and other UA researchers to apply dates and climate histories to an evolving understanding of ancient times.

The overall aspiration of the Center for Mediterranean Archaeology and the Environment is completion of a 10,000-year tree-ring chronology of the entire Mediterranean region.

The UA is an appropriate place for the investigation, said Kuniholm. It is the birthplace of tree-ring studies, first undertaken by astronomer A.E. Douglass, who wanted to compare climate to historical records of sunspots.

That never panned out, but when Douglass joined forces with archaeologist Emil Haury, they used the precision of tree rings and the climate record they contain to date the great pueblos of the Southwest and answer questions about why they were abandoned.

Continuing studies have answered riddles about the historical role of fire in the Southwest’s forests and the critical question of flows in the Colorado River’s watershed.

Kuniholm said Yenikapi has put some finishing touches on a similar accomplishment in the eastern Mediterranean.

“We were able to do in the Near East what has been done here in the Southwest,” he said.

The Yenikapi site is huge — half a mile by a quarter-mile with 39 shipwrecks, 46 docks and “oodles of stuff,” Kuniholm said. It contains sediment layers that document occurrence of an earthquake and tsunami in the region. At its lowest layer are preserved footprints from a Neolithic settlement dating to the 7th millennium B.C.

It’s all good stuff for the “pots and pans” people. But for Kuniholm, Pearson and the tree-ringers, the wood is the real treasure.