A University of Arizona researcher has escaped from the grasp of the Baga Serpent, at least for now.

An appeals court in New York has dismissed a multimillion-dollar lawsuit against UA radiocarbon-dating expert Greg Hodgins over a prized African wood carving of a snake that might not be as ancient — or valuable — as originally thought.

The unusual case involves a wealthy collector, a sketchy New York art dealer and some hapless scientists who stumbled sideways into an ethnographic mystery turned legal mess.

According to court records, Dr. Martin Trepel bought the 8-foot-tall serpent in 1992 from a dealer named Mourtala Diop.

The retired radiologist and self-described “investor in rare and valuable African tribal artifacts” paid $15,000 for the sculpture. But he later insured it for $15 million after experts told him it had been carved from a bark cloth tree at least 200 years ago by a member of western Guinea’s Baga tribe.

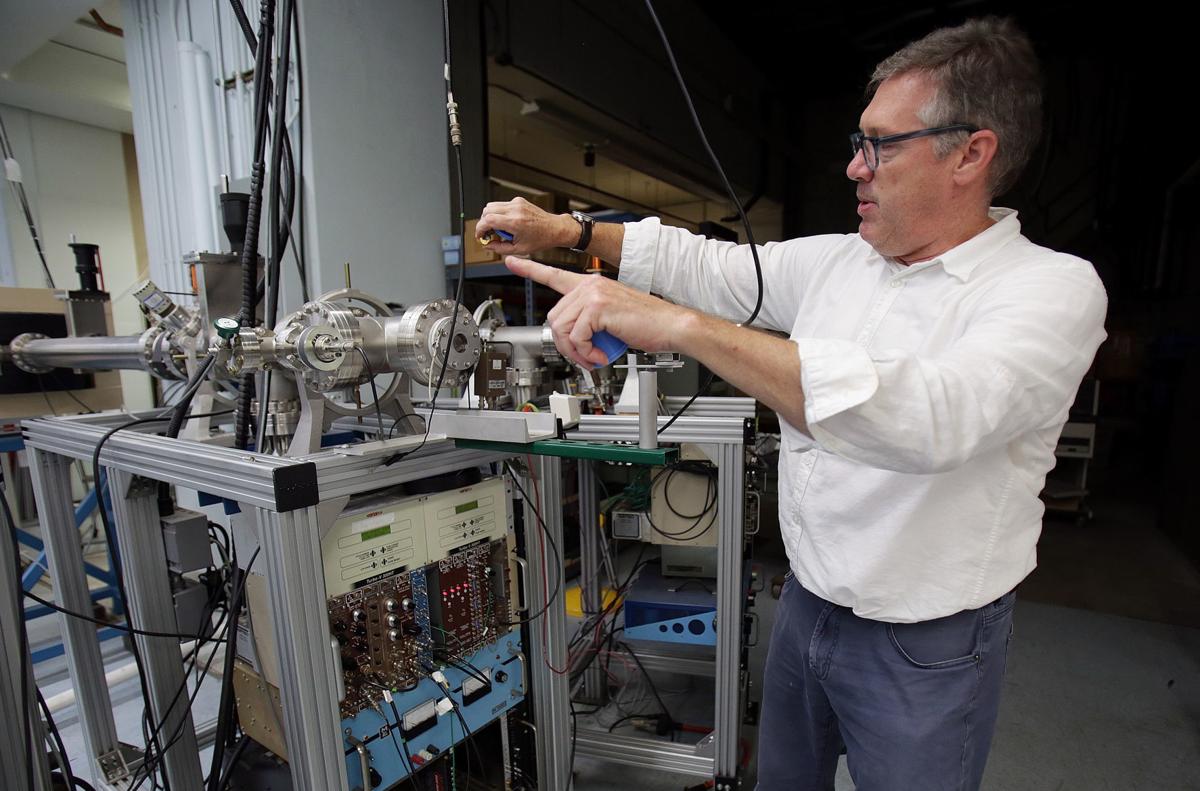

To fully authenticate his purchase, Trepel turned to Hodgins, director of the UA’s Accelerated Mass Spectrometry Lab, to conduct a carbon-14 analysis of the serpent.

Twice in 2016, Hodgins traveled to New York to collect tiny samples from the carving — first for the initial testing, then to confirm his startling results: This supposedly ancient work of art came from a tree cut down sometime around 1975.

A signature left by atomic blasts

Carbon dating uses the naturally occurring radioactive isotope carbon-14 absorbed by living organisms to determine the age of organic material.

By comparing samples to known levels of atmospheric carbon-14 from the past 60,000 years or so, scientists can accurately determine how long ago an organism lived and died.

The method has revolutionized research across disciplines, but it doesn’t always work that well for objects from the past 500 years, because the estimated age range produced by the analysis can be too wide to be scientifically useful.

One exception is organic material that was alive during the “nuclear age,” when above-ground atomic tests caused a tiny but unmistakable spike in global atmospheric carbon-14 levels in the late 1950s and 1960s.

Each time Hodgins tested samples from different parts of Trepel’s serpent, he found telltale signs of so-called “bomb carbon,” proof positive that the wood came from a tree that was still alive and growing less than 60 years ago.

Art dealer’s arrest clouds back story

Trepel knew what this could mean. Any test showing that the piece was modern or otherwise inauthentic would destroy its value.

He showed the Hodgins report to Sturt Manning, director of the Tree-Ring Laboratory at Cornell University, hoping for a second opinion. Manning agreed with Hodgins’ findings.

Trepel responded by suing both researchers and their employers in February 2018.

“He alleged everything under the sun,” including breach of contract terms that never existed in the first place, said Ed Lenci, the New York attorney who represented Hodgins and the Arizona Board of Regents.

“But he basically got an answer he wasn’t looking for twice.”

Trepel had some reason to doubt the serpent’s age.

In 2002, Mourtala Diop, the art dealer who sold him the carving, was arrested in New York City after Trepel reportedly paid him $242,000 for six supposedly 2,000-year-old terra cotta statues that turned out to be fakes.

Trepel told the New York Post at the time that one of the statues was 50 years old and another was just 25 years old.

The Post reported that when police searched Diop’s two Manhattan apartments, they found “more than 100 full and partial statues he — not African tribesmen — appeared to have made.”

Trepel later sued the art dealer for fraud and won a default judgment, but the Baga Serpent kept its place in his collection.

“frivolous” lawsuit could live on

Trepel continued to stand behind the serpent’s authenticity, even when his lawsuit over the radiocarbon results was falling apart.

In October 2018, a New York trial court declared the action “frivolous” and dismissed it on the grounds that Trepel waited too long to file it.

The state appellate court unanimously upheld that decision on May 7, ruling that even if the lawsuit had been filed in a timely fashion, New York has no jurisdiction over claims made against an agency of another state.

Lenci said Trepel, now in his early 90s, could try to convince New York’s highest court to hear his case, but he faces an uphill climb based on the two lower-court rulings.

“He can try. I don’t think he will succeed,” Lenci said.

Trepel, who has homes in Florida and New York City, could not be reached for comment.

Messages left for his attorneys were not returned.

When contacted by the Star on Wednesday, Hodgins said he would be delighted to talk about the case, but he couldn’t discuss it without approval from the university’s general counsel.

Science denied or science delayed?

As celebrity astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson is fond of saying, “The good thing about science is that it’s true whether or not you believe in it.”

Lenci seemed to make a similar point in his brief to the appellate court late last year.

“At its heart, this case is about the denial of science,” he wrote, “sadly a sign of our times.”

But it might not be that simple.

Even Lenci concedes that Trepel has “never wavered from his contention that the piece was hundreds of years old and very valuable.”

To bolster his case, Trepel had his Baga Serpent examined by several experts from prestigious institutions, among them a botanist who examined its wood, an entomologist who gauged the age of its insect boreholes, and a museum director whose specialty was African art. All “affirmed its venerable age,” according to the collector’s lawsuit.

So did Frederick Lamp, the retired director of African Arts at Yale University who has lived with and extensively studied the Baga people of Guinea for years. Trepel claims in court documents that Lamp considers his serpent “the most significant and striking example of the genre known to Western scholars.”

The lawsuit calls it “the most studied and validated work of African tribal art in the world.”

Hodgins’ findings cut at the heart of that validation. Two divergent sets of observations, pointing to two wildly different conclusions.

It seems like just the sort of puzzle scientists live to solve. Once the legal fight ends, maybe they will.