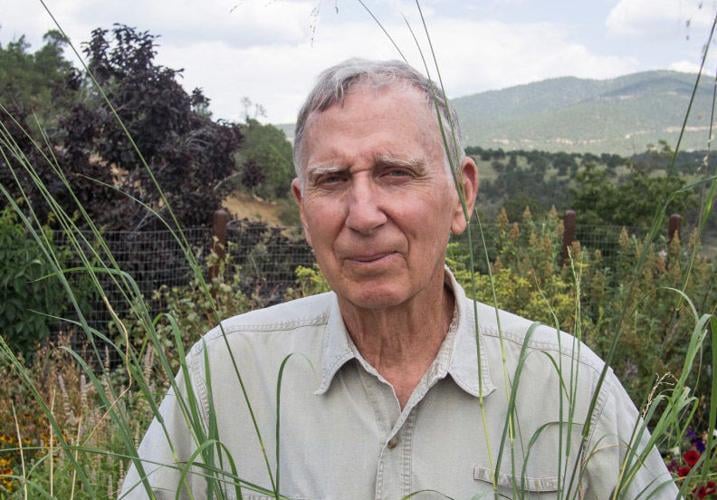

In a desert famous for its giants, Richard Felger became one himself.

The Tucson-trained ethnobotanist, arid-land expert and poet founded the research department at the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum and authored multiple books and more than 100 scientific papers about desert plants and desert people, among other topics.

Felger died at his home in Silver City, New Mexico, on Oct. 31. He was 86.

“He was one of the most knowledgeable people of the Sonoran Desert,” said Ben Wilder, director of the University of Arizona’s Desert Laboratory on Tumamoc Hill. “They do not make human beings like him very often.”

Felger’s work spanned a wide range of subjects, from sea turtle conservation to the study of desert-adapted food crops to fight hunger and bring agricultural independence to arid places. Much of his research focused on desert flora and the native people who have subsisted on it, particularly in Sonora.

Wilder, who co-authored “Plant Life of a Desert Archipelago” with Felger in 2012, described his mentor as a careful, rigorous scientist with a “ridiculous work ethic.”

He was also eccentric. Depending on his mood or who he was talking to, he could be crusty or kind, gentle or impatient, serious or completely irreverent, Wilder said.

“He literally taught me how to be a scientist,” Wilder said. “He set me on my path. He opened the world to me.”

Southern Arizona botanist and independent researcher Sue Carnahan first met Felger when she needed help identifying plants she had photographed in Sonora. She ended up collaborating with him on a 2017 book about the flora of a Sonoran canyon and helped him finish one several life-spanning projects – a 1,000-page reference on the plants of Mexico’s Guaymas region, at the southern edge of the Sonoran Desert.

Almost everything in the book is the result of his own first-hand measurements and observations, Carnahan said. “He always said, ‘Better to have no data than the wrong data.’”

Richard Stephen Felger was born in Los Angeles and shaped by childhood trips to the beach, where he found his calling in tidepools and whatever washed up on shore. A grade-school birthday gift of cactus and succulents sent him off into the world of plants.

“He used to say, ‘I was a marine biologist before I became a botanist when I was 8,’” Wilder said. “He just started going crazy growing plants in the backyard.”

By the time Felger graduated high school, his palm-like cycads towered over the house.

A field trip to Alamos, Mexico, with some ecology students from UCLA sparked his interest in all things Sonoran.

“That was it. As he said, ‘I saw the good stuff,’” Wilder said.

The experience led him to enroll at the UA because it was as close to Sonora as he could get. His weekends, school breaks and summers were spent exploring the desert, beaches and islands of the Gulf of California.

He went on to write his dissertation on the plants of that area, forging in the process a lasting connection with native Seri and Yaqui people there.

After receiving his doctorate from the UA in 1966, Felger served on the faculty at the University of Colorado, Boulder, and then as senior curator of botany at the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History.

He also hobnobbed with members of the Beat Generation and other well known writers and scientists of the time, leading him to publish a book of poetry called “Dark Horses and Little Turtles” in 1974 (and rerelease it earlier this year).

Felger returned to Tucson and worked at the Desert Museum from 1978 to 1982. He went on to found the Drylands Institute and serve as an adjunct senior research scientist at the UA Environmental Research Laboratory and an associate researcher at the UA Herbarium.

After trading a house near the UA campus for some horse property just outside of Oracle, Felger and his wife, Silke Schneider, eventually moved to Silver City in 2006. It’s tempting to say they retired there, “but Richard never retired,” Wilder said. “I would say he migrated to higher elevation.”

Felger’s credits so far this year include two scientific books and a journal article he co-authored. At least three more books with his name on them are slated to be published after his death.

Those who learned from him expect his research to live on for decades or even centuries to come.

“His attention to detail and his perfectionism were unequaled,” Wilder said. “I really do think his work will stand the test of time because of that.”