Engineering professor Sol Lim hadn’t even finished her first year at the University of Arizona when the coronavirus crashed down on top of her research.

Lim studies body mechanics in search of ways to improve occupational safety and people’s general well-being. A lot of her research involves recording the movements of human test subjects — some of them elderly, disabled or both — by attaching sensors to their bodies.

That’s hard to do when you’re not supposed to get within 6 feet of anyone.

“Basically, my work involves a lot of human participation,” Lim said. “And I’m working with a population that is vulnerable.”

When the virus hit, she had no choice but to shut everything down.

Lim is one of hundreds of UA researchers impacted by the pandemic, which sidelined everyone from seasoned, long-time professors to undergraduates eager for their first taste of college-level lab work.

Some of the scientists who were locked out by the university in early April found innovative ways to keep their experiments going by using cameras and remote sensors to collect data. Others, like Lim, were forced to temporarily suspend their projects or shift their focus to things they could do from home.

Now the labs have begun to open back up at the UA, even while COVID-19 cases surge and university officials struggle with whether to reopen for in-person classes this fall. A little over half of all active research activity has resumed, according to Betsy Cantwell, senior vice president for research and innovation at the university.

“We’re ramping back up,” she said.

But some researchers are still reluctant to bring their teams back to campus. And those who have returned face a shortage of student assistants, travel restrictions that make some field work impossible, and a slate of new safety requirements.

“Nobody’s operating without a face covering. Nobody’s operating without social distancing,” Cantwell said. “In order to operate, you have to tell us how you’re going to operate safely, and we have to validate your plan.”

Critical research allowed to continue

Science is big business at universities like the UA.

Approximately $732 million worth of research was conducted at the institution during the fiscal year that ended in July 2019.

Cantwell said university officials began planning for a possible research shutdown in mid-March. Working groups were formed and protocols were developed in consultation with each department.

The closure finally arrived on April 1, two days after Gov. Doug Ducey imposed a statewide stay-home order. Researchers were given until April 8 to shutter all nonessential research laboratories and facilities.

Among those especially hard hit were clinical researchers whose work requires close contact with people, and scientists who are studying sites or conducting experiments far from campus.

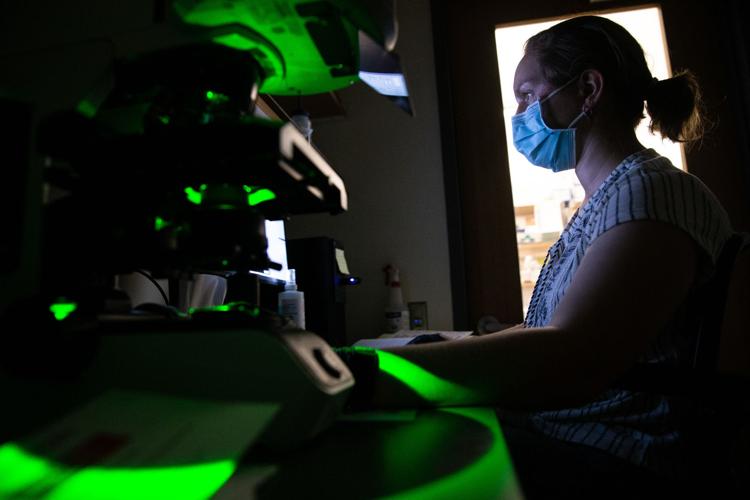

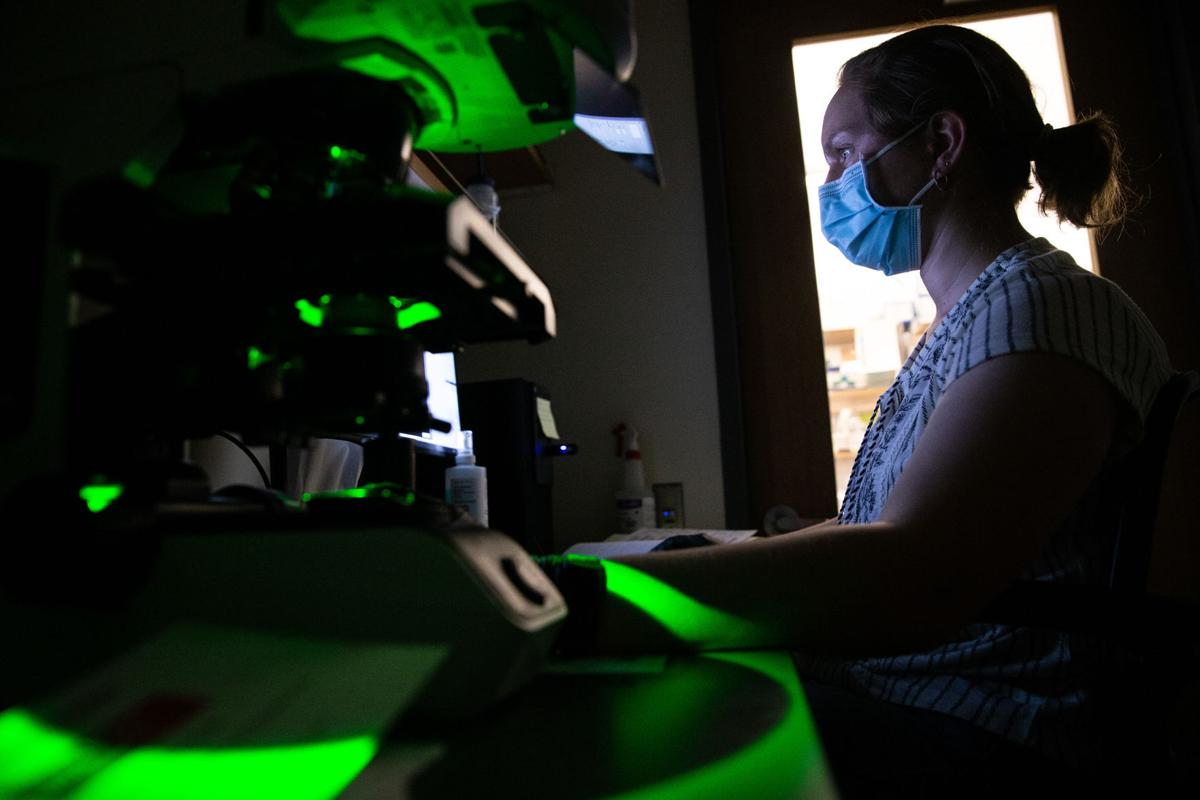

Tubes hold tissue cells for testing at a UA research site. Labs are opening back up, even while COVID-19 cases surge and the school struggles with whether to reopen for in-person classes this fall.

“If it’s out of state, the work in the field (wasn’t) happening,” Cantwell said.

Not everything was shut down.

The university granted roughly 200 waivers for critical research, which Ducey’s order allowed but did not define.

Some waivers were almost automatic.

“Especially the space missions — they can’t slow down,” Cantwell said. “They have launch dates that don’t care (about coronavirus). They’re picked based on the physics.”

Also exempt was research related to COVID-19 or the treatment of people infected with the virus.

“They meet the very definition of criticality,” Cantwell said.

Other projects deemed critical were ones that could not be stopped without causing catastrophic damage, either through the loss of samples and test subjects or an interruption in long-term observations where continuity was key.

Some students received waivers for experiments they needed to finish in order to graduate in the spring.

Exceptions were also made to allow for the periodic maintenance of sophisticated and expensive equipment that could fail if it wasn’t activated or checked on every now and then.

Cantwell said most researchers who applied for waivers were granted them. What impressed her was how many scientists determined on their own that their work, while incredibly important to them, wasn’t necessarily worth the risk during a pandemic.

“I cannot tell you how impressed I am with the research cadre at the U of A,” she said. “They all want to get back to work, but they understand that not everything is critical.”

Ripple effects could be felt for years

The work being done by assistant professors Andrea Achilli and Kerri Hickenbottom seems pretty essential. All they’re trying to do is solve the West’s water problems.

Specifically, their research revolves around squeezing every usable drop out of water systems in arid places while safely disposing of brine from the treatment process.

Achilli said they had just gotten a new project going when “everything had to stop” in early April. “That was a big setback.”

They expect the ripple effects from the shutdown to last for the next year or two at least. “One way or another, there’s going to be less money” for research, Achilli said.

Their current work is funded by grants from the U.S. Department of Energy, the Bureau of Reclamation, the city of Phoenix and the Salt River Project, among others.

Hickenbottom said they will probably need to ask those funding agencies for more time to complete their research. Working remotely has definitely slowed things down, she said. Things that used to be easy, like running to the hardware store for plumbing parts, suddenly became complicated by COVID-19 .

The shutdown also raised storage challenges, since some of their filtration systems are too large to stick in a closet and have components costing many thousands of dollars that can deteriorate if they sit dormant for too long.

Thanks to the waiver process, they never had to fully close up shop. Hickenbottom said that has allowed them to keep at least some of their students occupied this spring and summer.

“I could tell they were getting antsy,” she said. “There’s only so much binge-watching they can do.”

No one was allowed back into the lab without following strict safety guidelines, Hickenbottom said.

“We made it very explicit, and they were very careful,” she said of their student researchers.

Achilli said their location helped to an extent. They work off campus at the UA’s WEST Center — short for Water and Energy Sustainable Technology — next to the Pima County Wastewater Plant near I-10 and El Camino del Cerro.

“It’s a new facility. It’s not crowded. We feel safer here,” Achilli said.

Both assistant professors said they worry about what might happen to their students if the entire university returns to normal operations in the fall.

The UA officially reopened for research on May 15, when Gov. Doug Ducey lifted his stay-home order, but the reentry process didn’t truly begin until June 1.

Hickenbottom said she has been encouraging her graduate and undergraduate students to lighten their class loads and delay any course work they can, at least until second semester, to limit the amount of time they have to spend on campus.

gradual return to a new normal

The UA officially reopened for research on May 15, when Ducey lifted his stay-home order, but the reentry process didn’t truly begin until June 1. That’s when Cantwell and company rolled out a new review process that requires researchers to submit a safety checklist before returning to the lab.

By last week, 542 such checklists had been approved. Masks and gloves are now required where they haven’t been before, and work schedules are being adjusted to limit the number of people in the lab at any one time. Some facilities have put markings on the floor to help maintain social distancing.

So far the approach appears to be working.

As of about 10 days ago, Cantwell said, only about five people within the university’s research community had tested positive for COVID-19, and there were no reports of transmissions among research staff members.

She said she has not heard any reports so far of research projects that have been ruined completely or stripped of their funding as a result of the shutdown.

“We worked really hard to make sure that didn’t happen,” Cantwell said.

Originally she had hoped to see research work at the UA back to about 80% of where it was before the shutdown, but she acknowledges now how “unrealistic” that is given Arizona’s growing COVID-19 caseload. Something more like 60% to 65% seems more achievable.

Cantwell declined to predict when the business of research might completely return to normal. She said some things will probably never go back to the way they were.

“The community aspects of science are going to change,” she said.

Test subjects may decide to stay home

Lim and her team of biomedical researchers are now trying to develop new ways of working with human test subjects without risking anyone’s health.

One idea involves converting a section of their lab into a safe zone where volunteers can come in and attach sensors to themselves while researchers feed them instructions over a computer link from a safe distance away.

For one of her projects, Lim and her team are trying to create a virtual learning system that will teach yoga to the visually impaired.

“Without visual feedback, it’s hard to strike the right poses,” she explained, so their system would attach to a person’s body and guide them through their exercises using other sensory feedback.

Of course, none of this will work without people to test it on.

Lim worries that it could be a long time before test subjects feel safe enough to participate in her research once again, even for the modest payments they receive for their trouble.

“Before COVID, people were very excited to participate in our study,” Lim said. “Participant recruitment will be a big thing.”

On the plus side, the coronavirus pairs nicely with her team’s effort to develop ways for vulnerable populations to do more on their own so they don’t have to go out and risk infection.

“With our virtual learning system that we’re developing, we hope people can still enjoy physical exercising without any barriers like inaccessibility or travel difficulties,” Lim said.

From twiddling knobs to solving equations

Oliver Monti is a professor of physics, chemistry and biochemistry whose research focuses on understanding the basic properties of advanced, super-thin materials that could produce the next generation of electronics and renewable energy systems.

His trademarked MontiLab has “world-leading equipment sitting in crates waiting to be installed,” he said, but he is in no rush to reopen the facility with coronavirus cases on the rise like they are.

The shutdown has been a big test for him and his team, who are used to being in a climate-controlled room full of lasers, vacuum equipment and other instruments, some so large they can only be lifted with a crane.

“My people are well trained as experimentalists. They stand in the lab and twiddle knobs, observing and collecting data,” Monti said. “But that’s basically been impossible. We more or less locked up the lab.”

So they’ve hit the books and the blackboard instead.

“We had to pivot. We’re all learning together to become theorists,” Monti said. “We are digging in and really making the most of what we can do from home, with modeling and theory projects.”

At this rate, he’s not sure when it will be safe for him and his students to return to the lab.

Already, he said, he’s hearing that the university might pull back from its current reopening plan to something more restrictive with fewer researchers allowed on campus. There has been no talk so far of another shutdown, but what’s going on across the state doesn’t exactly fill Monti with confidence.

“We are very much discouraged by the current situation,” the researcher said. “It’s really heading the wrong way at the moment.”