No airplanes crashed and no buildings collapsed here, but the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, sent shockwaves through Tucson.

Those ripples can still be felt.

Here are seven stories from that indelible day and the 20 years since.

Facing forward

Christie Coombs will spend the 20th anniversary of 9/11 volunteering near her home in the Boston area, as she usually does.

The Yuma native and University of Arizona graduate is slated to start her day greeting donors at the annual blood drive at Fenway Park, then move on to Rose Kennedy Greenway to help a group of eighth graders assemble care packages for veterans serving overseas or living on the streets of Boston.

People keep asking her how she feels about today, she said, but nothing seems like a milestone when everything does.

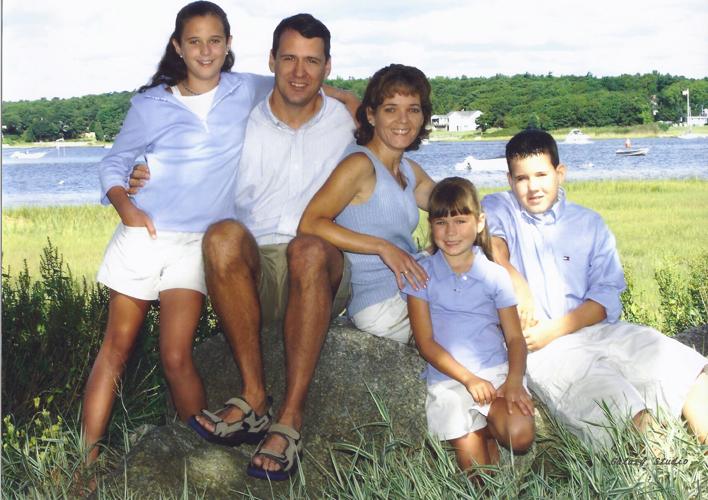

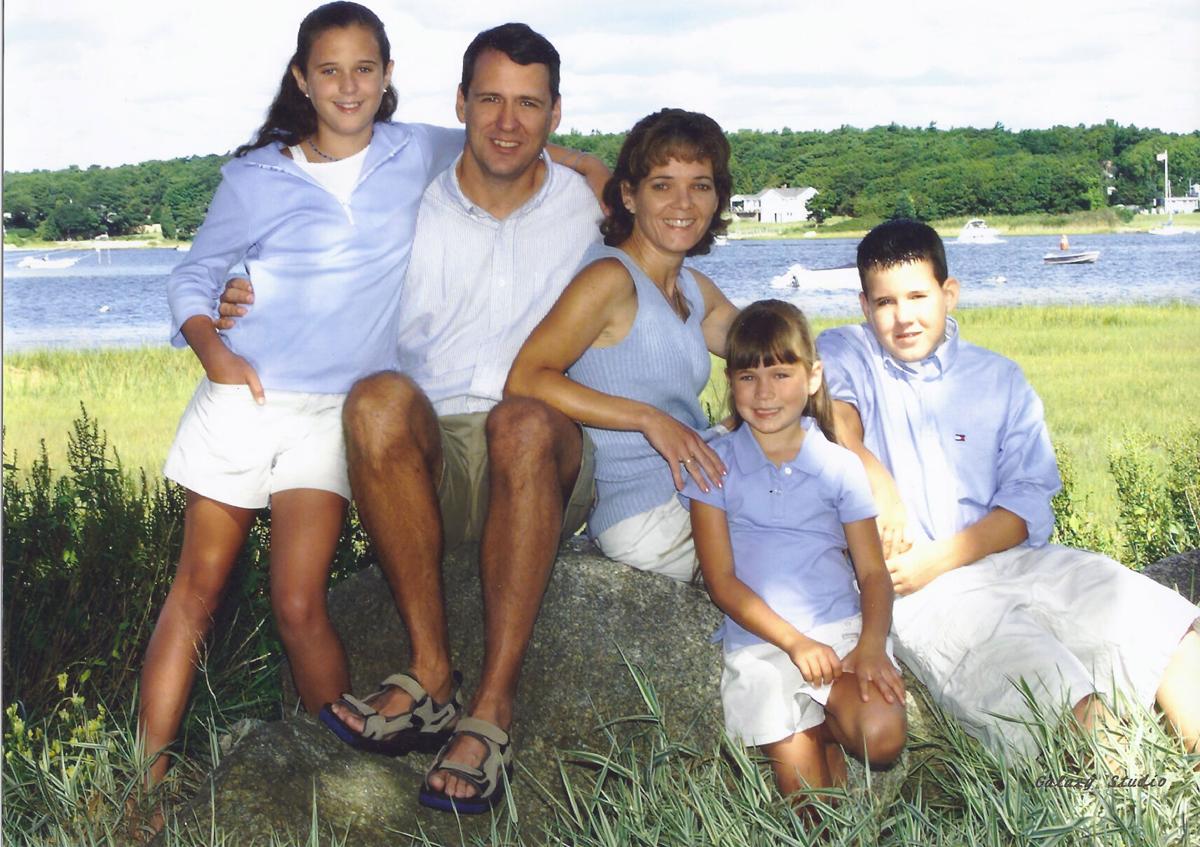

“It’s not more or less powerful than any other day. It just signifies 20 years since I’ve seen my husband, 20 years since my kids have seen their father,” Christie said.

Jeffrey Coombs, 42, was a passenger on American Airlines Flight 11 when it crashed into the north tower of the World Trade Center.

Christie has seen the footage of his death more times than she can count. She knows she will see it again. She has almost gotten used to the way it pops up without warning sometimes when she turns on her TV.

“It comes at you when you least expect it, especially this time of year,” she said. “You can’t get away from it.”

One thing will be different this year.

On Sept. 19, Christie will preside over the final Jeff Coombs Memorial Road Race, Walk and Family Day, a fundraising run that has been held annually since 2002.

“This is really and truly it,” she said. “It just feels like the right time to let it go.”

About 30 of Coombs’ family members, most of them from Arizona, are traveling in to attend the final race. The Beantown Cats, a Boston-area U of A alumni group, are also expected to take part, just like they usually do.

The event in Abington, Massachusetts, south of Boston, has drawn as many as 1,400 participants and raised as much as $100,000 in the past, but Coombs hopes to close it out in style by beating those records this year.

All of the proceeds go to the Jeff Coombs Memorial Foundation, which provides financial assistance to Massachusetts families who are struggling because of death, illness or other hardships.

Coombs said she and her children created the fund in November 2001, when she was still “trapped by the dark hole of grief.” It was inspired by the enormous outpouring of support their family received after 9/11.

“So many people came out of the woodwork — friends, strangers, family, not just across Massachusetts but across the country,” she said. “There were all kinds of nice gestures.”

The foundation has since raised and distributed more than $1 million to others in need, with a special emphasis on military families in the Bay State.

Jeff grew up in Massachusetts, then enrolled at the U of A because he wanted to experience someplace different far from home, Christie said. Until he arrived in Tucson to start classes, he had never been to Arizona.

Christie and Jeff met at his fraternity house in 1978. She said he was busy fixing a door and basically ignored her the first time they spoke, but he noticed her soon enough. They started dating that spring.

She describes Jeff as a “tall, funny, kind and goofy Bostonian,” who loved the outdoors.

“Our deal when we got engaged was I would get a ring, and he would get a canoe,” Christie said.

He graduated with a business degree in December 1981. She graduated with a journalism degree in May 1982. They got married in 1984 and briefly lived in Phoenix, until a job opportunity drew Jeff back to Massachusetts with his new bride.

On Sept. 11, 2001, he was supposed to fly to Los Angeles for a business conference. When he left for Boston’s Logan Airport that morning, he told Christie he would be home in time to celebrate their September birthdays together — hers on the 15th, his on the 18th.

University of Arizona students attend a candlelight vigil at the Newman Center on Sept. 11, 2001.

A few hours later, she turned on the TV news and saw black smoke pouring from the North Tower.

“It took a while to figure out that that was Jeff’s plane,” she said. “My house was filling up with people as word got out.”

An official from American Airlines called at just after 1 p.m. to confirm the worst.

“The hardest thing I had to do was tell the kids their dad wasn’t coming home,” Christie said.

Their son was 13, and their daughters were 11 and 7.

Volunteering gave Christie a way to rechannel her sorrow into something positive.

She now serves on the board of several service organizations, including her local education foundation, the American Red Cross Blood Services Division and the Massachusetts Military Heroes Fund.

She finds herself gravitating toward veterans’ causes because of a connection she feels to those who joined the military in response to the 9/11 attacks. In some strange way, she said, “I felt a responsibility for that.”

Christie still lives in the house she shared with Jeff and the kids. The boots and muddy T-shirt he wore while digging the footings for their deck still hang above his work bench.

Today their son is 33, with a wife and 1-year-old son of his own. Their oldest daughter is 31 and just got married in June. Their youngest daughter, now 27, will walk down the aisle in October.

Christie doesn’t like the phrase life goes on. Something about it suggests forgetting the past or trying to erase it.

She can’t help but think about her husband. She remembers him everyday, then she gets to work.

“I say life goes forward,” Christie said.

Warrior class

One Tucson school lost more than any other in the fighting that followed the terrorist attacks.

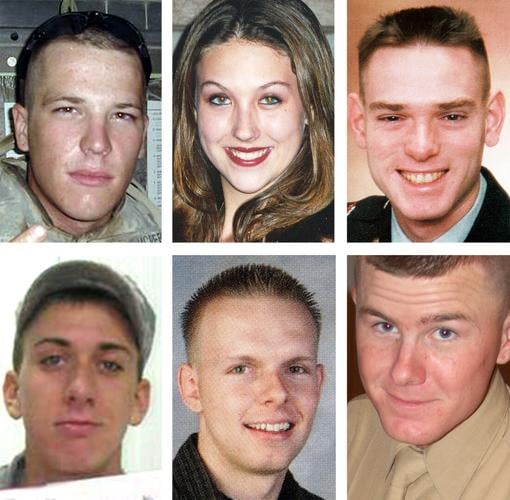

Six former students from Mountain View High School died while serving in the military after 9/11.

Three of the fallen came from the Class of 2004 and died in Iraq within 2 years of each other.

Army Pfc. Sam Williams Huff, 18, and Navy Hospitalman Chadwick T. “Chad” Kenyon, 20, were both killed in roadside bomb attacks — she on April 17, 2005, he on Aug. 20, 2006. Army Spc. Alan McPeek, 20, was killed in action on Feb. 2, 2007, on what was supposed to be his last day in Iraq.

Army Sgt. Kenneth Ross, a 24-year-old who graduated from Mountain View in 1999, served in Iraq and then died in Afghanistan when his helicopter crashed on Sept. 25, 2005.

A roadside bomb in Iraq killed Marine Lance Cpl. Budd M. Cote, 21, on Dec. 11, 2006. He attended Mountain View for his junior year and part of his sophomore year in 2002 and 2003.

Army Spc. Nathan Spangenberg, 21, survived a 15-month tour in Iraq, only to be found dead in his barracks in Hawaii from an illness on Sept. 8, 2009. He attended Mountain View from 2004 to 2006 and joined the military in 2007.

Mountain View High School students who died while serving in U.S. Armed Forces after Sept. 11, 2001. Top, from left: Alan McPeek, Sam Huff, Kenneth Ross. Bottom, from left: Nathan Spangenberg, Chad Kenyon, Budd Cote.

The casualties from the high school at Thornydale Road and Linda Vista Boulevard represent 10% of the roughly 60 service members with ties to Southern Arizona who have been killed in Iraq and Afghanistan. No other high school in the United States is known to have lost so many former students.

The school’s grim luck made national headlines. After McPeek was killed, the San Francisco Chronicle called Mountain View “war’s chosen high school.”

Long-time Marana School District teacher Mike Dyer didn’t know any of the six students, but he certainly understands where they came from and their desire to serve.

The Ajo native earned a Purple Heart as an Army sniper during the Vietnam War, then returned to Arizona for a 40-year career as an educator and state and county Hall of Fame girls basketball coach, most of it at Marana High School.

He joined the staff at Mountain View in 2004, about nine months before the string of combat deaths began.

Dyer said his fellow staff members “talked about it some, but everybody just went about their lives.”

“That’s pretty common,” he said. “The war wasn’t affecting them. If it’s not immediately affecting people, they go to work and go home and that’s it.”

But as time passed and more former students fell, Dyer dedicated himself to making sure their sacrifice was not forgotten.

“The Marana area and this district have a long tradition of people serving our country,” he said. “I just felt something needed to be said and done to recognize the kids that have been killed that have gone to Mountain View.”

Dyer also serves as commander for the local chapter of the Military Order of the Purple Heart, a service organization of — and for — wounded veterans. It took him and his fellow chapter members about three months to raise $5,000 for a permanent memorial at Mountain View.

Mike Dyer, a former teacher in the Marana Unified School District and an Arizona High School Athletic Coaches Hall of Famer, sits on the bench at Mountain View High School that is a memorial to former MVHS students who lost their lives while serving in the U.S. Armed Forces after 9/11.

The brick and concrete bench was installed next to the school’s flag poles in the fall of 2014, a few months after Dyer retired from teaching. He was there to lead the dedication ceremony, which included a salute by four riflemen.

The simple monument includes metal seals from each branch of the military and a plaque that talks about sacrifice.

“We ask people to think about what those people have done for them while they’re sitting at the bench,” Dyer said.

The names of the six fallen students do not appear anywhere on the memorial, he said, because some of their families were not comfortable with that.

“A lot of people at that time thought that generation was worthless. ‘They were spoiled brats. They didn’t care about the country,’” Dyer said. “But when 9/11 hit, every one of those young kids couldn’t wait to join and fight for our country. It just speaks volumes for that group, and it’s continued for 20 years.”

There is no way to explain — beyond simple, random chance — why so many Mountain View students were lost to war. Dyer said the school “certainly didn’t have more people in combat than anybody else.”

That three were killed from the same graduating class is nothing more than an awful coincidence, he said. “Bad things happen to good people. That’s just the way it is.”

Towering tributes

As ground zero was cleared of debris, select pieces of the twin towers were hauled to a hanger at New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport as artifacts of the atrocity.

Thousands of relics were preserved inside Hangar 17, including twisted sections of building steel, crushed emergency vehicles and subway cars, pieces of the North Tower antenna and merchandise from the retail stores in the World Trade Center plaza.

In 2010, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey began to distribute the items a few at a time for public memorials at museums, parks, police stations and firehouses across the country. Over the next six years, the artifacts giveaway program sent more than 2,600 pieces of steel and other material to communities in all 50 states and several foreign countries.

“Each artifact from Hangar 17 is a piece of history that tells a special story about 9/11, such as firefighters and rescuers running into the burning towers to save those who were in the greatest need,” said Joseph W. Pfeifer, then the chief of counterterrorism and emergency preparedness for the New York City Fire Department, in a statement marking the end of the giveaway program in 2016. “The 9/11 steel, whether small or large, represents the 343 firefighters who were lost, as well as all victims of terrorism throughout the world.”

Twelve of the memorial shipments from ground zero landed in Arizona for public exhibits from Yuma to the Grand Canyon, Sierra Vista to Salome. One section of I-beam was given to the Transportation Security Administration in Phoenix, which puts it on display each year on 9/11 at one of the state’s three largest airports.

Pima County’s piece of the twin towers rests near the Little League ballfields at Kriegh Park in Oro Valley, where it anchors a sculpture called “Freedom’s Angel of Steadfast Love.”

The sun peeks through the Freedom’s Steadfast Angel of Love statue at the James D. Kriegh Park in Oro Valley. The 9-foot-11-inch statue incorporates steel from the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, artifacts from the firetrucks buried at the twin towers and rocks from the Pennsylvania field where Flight 93 crashed.

The display erected in 2011 includes damaged steel salvaged from the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, parts of fire trucks plucked from the rubble, and rocks collected from the Pennsylvania crash site of United 93. Rising above it all is the metal silhouette of an angel — 9 feet 11 inches tall and dark with rust a decade after its dedication.

The memorial was placed in the park to honor the Old Pueblo’s best known 9/11 baby, Christina-Taylor Green, who died along with five other people in the Jan. 8, 2011, mass shooting in Tucson that targeted then-Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords.

Green, who would have turned 20 today, used to play baseball on the fields where the angel now stands.

Through security

On Sept. 11, 2001, Justin Testerman was in his third week as a gate agent for America West Airlines at the Tucson airport.

He and his coworkers had just sent off their first flight of the morning when they heard screams from a group of people gathered around the television at the concourse bar. Then the teletype machine at their gate began to buzz with an urgent message: Airplanes have hit the World Trade Center. Stand by for further instructions.

A short time later, Testerman and his fellow gate agents were sent down a nearby jetway to search for bombs or other suspicious items on a Continental Airlines plane set to fly that morning.

“Keep in mind that we didn’t really know what suspicious meant,” he said.

His experiences that day inspired him five months later to apply for a job with the newly formed Transportation Security Administration, which Congress created in November 2001 to take over screenings at the nation’s airports.

“It was a chance to stand up and do my part,” Testerman said. “I just felt a call to serve.”

So did a lot of other people. Between February and December 2002, the TSA reviewed roughly 1.7 million applicants for 55,000 screening jobs nationwide. The effort has been called one of the largest government staffing initiatives since World War II, and Testerman was among the first training specialists to be hired.

His job was to go from airport to airport, coaching new security screeners, calibrating their equipment and getting them ready to stand on their own.

Charles Sparks, assistant federal security director, left, and Justin Testerman, training specialist, were hired in the months after 9/11 to help establish the new Transportation Security Administration at Tucson International Airport.

His first assignment was at JFK in New York, where he spent five weeks interacting with people still raw from losing loved ones in the attacks.

The unwritten mission of TSA is to make sure nothing like 9/11 ever happens again, Testerman said, and his time at JFK helped “cement that mindset: not on my watch.”

After a few more assignments at cities across the Northeast, he was sent back to “his” airport in Tucson, as TSA prepared to replace the airline contractors that previously ran the checkpoints.

The transfer took place Oct. 1, 2002.

“I literally shook hands with them and took over,” Testerman said.

That moment was made possible by a small group of people who worked frantically behind the scenes to stand up TSA’s new operation in Tucson in a matter of weeks.

Charles “Sparky” Sparks, now the assistant federal screening director for the agency here, said it was up to him and four or five others to build the organization from scratch.

When he was hired in early September 2002, he said, “we had a box of radios and a stack of legal pads, and we took off from there.”

It turned out to be the perfect job for Sparks, who developed a taste for rapid-fire training and logistics during his career in the Air Force and later as a civilian contractor at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base.

“It’s fun if you enjoy that sort of thing, and I do,” he said.

By the end of 2002, Sparks and company had staffed up to about 250 employees and built a new electronic baggage screening system in the bowels of the airport.

Then, “with the wind blowing underneath the terminal on New Year’s Day 2003,” Sparks said, TSA started checking bags at the Tucson airport.

Today, technology improvements and other efficiencies allow the TSA in Tucson to operate with about 170 officers, 27 of whom have been with the agency since the beginning, just like Sparks and Testerman have.

“For whatever reason, they were drawn to serve, and they’re still there,” Sparks said.

The current staff ranges in age from 18 to 68 and includes both recent high school graduates and seasoned veterans of law enforcement and the military. The feedback they regularly receive on customer service surveys from passengers is so overwhelmingly positive it “almost brings a tear to your eye,” Sparks said. “People appreciate feeling safe.”

Today will not be a typical day at the airport. 9/11 never is, Testerman said.

“People are extra courteous with each other.”

The airport typically marks the anniversary of the attacks with an announcement and a moment of silence at exactly 5:46 a.m., the moment when American Flight 11 struck the World Trade Center.

Not many people will need the reminder, Sparks said. “A lot of these passengers, they’ll know exactly what day it is.”

Al-Qaida in Arizona

There are 32 references to Arizona in the 9/11 Commission report, the government’s official, 585-page accounting of the events that led to the attacks. Tucson comes up four times, all in reference to people who lived here in the 1980s and early 1990s and were later linked by authorities to Osama bin Laden.

One of those men, Saudi-born Hani Hanjour, directly participated in the attacks. The 9/11 Commission identifies the 29-year-old as “the fourth pilot,” who steered American Airlines Flight 77 into the Pentagon.

A decade before that, Hanjour was a student at the University of Arizona’s Center for English as a Second Language and spent more than a year in Tucson, though he doesn’t appear to have left much of an impression.

In an exhaustive report in 2002, the Washington Post stitched together Hanjour’s movements leading up to 9/11 but found little to explain his turn toward extremism or his willingness to kill and die for the cause.

According to the Post, no one at the Islamic Center of Tucson recalled the man, and none of his instructors at the UA could pick him out of a photograph.

“An examination of Hanjour’s odyssey, drawn from interviews, flight training records, apartment rental applications and other documents, only deepens the mystery about his role,” the Post reported. “No one has been able to offer a definitive portrait of Hanjour, leaving unreconciled a number of seemingly contradictory facts about his life.”

Hanjour reportedly moved back to Saudi Arabia after studying at the U of A, but investigators say he returned to the U.S. in 1996 to attend flight schools in California, Florida and Arizona, where he lived for a time in the Phoenix area.

The eventual hijacker received a commercial pilot certificate from the Federal Aviation Administration in April 1999.

The 9/11 Commission concluded that Hanjour’s time in Tucson “may have been significant” because of the number of important al-Qaida figures who also attended the university or lived here in the 1980s and early 1990s.

That information comes from a CIA analysis titled, “Arizona: Long Range Nexus for Islamic Extremists,” which links Osama bin Laden to four former Tucson residents: Mubarak al Duri, Muhammad Bayazid, Wadih el-Hage and Wa’el Jelaidan.

Passengers sit in the terminal at Tucson International Airport after all air traffic nationwide was grounded on Sept. 11, 2001.

Authorities say al Duri and Bayazid procured weapons for the terrorist leader. El-Hage served as bin Laden’s personal secretary and is now serving a life sentence at a federal Supermax prison in Colorado for plotting the 1998 bombings of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania.

Jelaidan was president of the Islamic Center of Tucson from 1984 to 1985, then left the country in 1986 — with the tacit blessing of the U.S. government — to fight the Soviets in Afghanistan.

Two years later, he joined bin Laden and others to found al-Qaida.

Military response

Davis-Monthan commander Paul Schafer knew something was up when the command post hotline rang early that morning at his house on base.

The airman on the other end of the line spoke of hijacked airliners and explosions at the World Trade Center.

Schafer switched on the news and got to work.

The former A-10 combat pilot and instructor said he called a quick meeting of his senior staff and placed the installation on a security alert.

Before 9/11, Schafer said, you could drive onto the base with little more than a salute if you had a current sticker on your car. Starting that morning, anyone trying to enter was subject to a full ID check, a slower process that caused long lines at the gates.

“We backed traffic up onto the street,” said Schafer, then a colonel in his third month as commander of D-M and the 355th Wing. “Craycroft and 22nd was just a parking lot.”

Schafer and company also began preparations for what they knew would come next. Within a few days of 9/11, he said, they started getting ready to deploy.

D-M sent its first airmen into the field Sept. 23, 2001. By the end of 2002, Schafer said, roughly 1,000 Tucson-based service members had been deployed to more than 40 locations, where they flew hundreds of sorties and racked up more than 5,000 combat hours.

Then- Davis-Monthan AFB commander Paul Schafer

Meanwhile, back home, Davis-Monthan was busy reconfiguring its entrance gates to improve traffic flow and provide protection to the vehicles lined up waiting to get in.

Schafer said the base also upgraded an old hangar to support the Arizona Air National Guard in a crucial new mission not seen “since the Berlin Wall fell.”

As part of Operation Noble Eagle, the guard’s 162nd Fighter Wing has kept a contingent of F-16 fighter jets on 24-hour alert at D-M since 2002, ready to respond at a moment’s notice to possible threats across 225,000 square miles of the Southwest.

Bomb-sniffing dogs were employed at the entrance of Davis-Monthan Air Force Base on Sept. 11, 2001.

Schafer left Davis-Monthan in February 2003 to assume a leadership position at the Pentagon. He retired from the Air Force as a major general in 2011 and now works as a D.C.-area defense consultant and as a volunteer docent at the National Air and Space Museum.

To him, it feels like more than 20 years have passed since he answered that early-morning phone call at Davis-Monthan in 2001. The entire military community has been responding to those attacks for so long now, “it seems like forever ago,” Schafer said.

Some service members have literally spent their entire careers fighting the war on terrorism.

“The people who enlisted after 9/11 are now getting ready to retire,” he said.

Schafer can’t watch the news from Afghanistan without thinking of his own visit to Bagram Air Base and Kabul in 2005. During that orientation tour, he saw school girls in the Afghan capital who looked no different than “girls walking to school anywhere in Southern Arizona or the U.S.,” he said.

He worries about what will happen to the girls of Afghanistan now, but he’s not sure there was another way for the war to end.

“I’m saddened that it appears the outcome is going to be challenging for the Afghan people,” Schafer said. “But we couldn’t want it to be better; they had to want it to be better. We can’t want it more than the Afghanis want it.”

Lucky numbers

9/11 was the end for so many, but for one Tucson family it was only the beginning.

Jennifer Pucci went into labor sometime that morning, while the horror was still unfolding in lower Manhattan.

Not knowing what else to do, she had her mother-in-law drive her to Grace Christian School, where Jennifer’s husband, Anthony, was teaching fifth grade.

“I think I’m having contractions,” she told him.

“You can’t be here,” he said. “We’re evacuating.”

Jennifer returned home, switched off the news and tried to stay calm. Anthony got there a short time later, just in time to drive her to St. Joseph’s Hospital.

The Puccis could not escape the terrible news, even in the labor and delivery room.

“The TV was on, and I couldn’t focus to save my life,” Jennifer recalled. “You’re supposed to let your body relax, and I was like, ‘Are you kidding me?’”

She thought music would help, so Anthony sang songs into her stomach.

Their first child, a daughter, entered the world at exactly 9:11 p.m. on 9/11. One of the first things her parents gave her was a last-minute name change. Emily Ruth Ann became Emily Joy Ann, right there at the hospital.

“They say I was their joy on that day,” said Emily, who graduated from high school in 2019 and is now studying to become a nurse after a short stint in the Army.

Anthony Pucci holds his newborn daughter, Emily, as Jennifer smiles in the background at St. Joseph's Hospital in Tucson on Sept. 11, 2001.

She does not remember how old she was when she first learned about 9/11.

“I feel like I’ve always known,” Emily said.

Sharing your birthday with a national tragedy is a lot to ask of a child, and there were times growing up when it felt unfair to her.

“It was always strange to celebrate on a day that was obviously very hard for a lot of people,” Emily said. “It was always a sad day (at school). We would watch 9/11 videos in class, and my teachers would talk about where they were that day.”

It was hard on Jennifer, too — especially that first year, when the normal anxiety of being a first-time parent was compounded by life in an anxious and wounded nation.

“It was really emotional for me,” she said. “We were just a normal family, trying to take care of our baby and not correlate these two things.”

The Puccis moved away from Tucson in 2003, eventually settling in Las Vegas, though they return to the Old Pueblo several times a year to visit family and the neighborhoods where Anthony and Jennifer grew up.

The two met by accident one day while skipping out on youth group at church, Jennifer said with a laugh. They were high school sweethearts, despite attending rival schools — she at Sahuaro and he at Sabino.

After dating for about four years, the couple got married in 1998, the year before Anthony graduated from the University of Arizona with a degree in education.

Eighteen months after Emily was born, they welcomed their second child on another inauspicious date. Emily’s younger brother, Thomas, was born on the first day of the Iraq War.

When Jennifer was pregnant with their youngest, Josiah, she said friends would tease her about her knack for giving birth in the middle of major world events.

“They would tell me, ‘You better let us know when you go into labor, so we’ve all got time to find cover somewhere,’” she said.

The Puccis have tried to make their daughter’s birthday seem as normal as possible over the years — a family dinner at Red Lobster, a sleepover with friends — but it’s hard to keep 9/11 from seeping in.

The weight of that day really hit home for Emily in 2014, when she was 12 and the family visited ground zero during a cross-country road trip.

Emily remembers wandering off by herself to read the names etched into the memorial. She broke down when she came to one of the 11 women who are listed along with their unborn children.

This is what was happening to other families on the day she was born. How is a sixth grader supposed to process something like that?

“I remember crying really hard,” she said.

Even so, Emily has long considered 9 and 11 to be her lucky numbers, thanks in no small part to another amazing family coincidence: Her great-grandmother was born on Sept. 11, 1911.

“When she was 9, (Emily) was No. 11 on her softball team,” Jennifer said.

Eventually, the Puccis made peace with the dissonance of it all — a tragedy that’s also a birthday, a national day of mourning that’s also a celebration of life and family.

“It can be both. It doesn’t have to be one way or another,” Jennifer said.

Emily credits her faith for helping her make sense of it all. She comes from a deeply religious family, she said, and she always takes time on Sept. 11 to say a prayer for those who were lost and those who lost someone.

Her parents, meanwhile, try to focus on the blessings they received on 9/11 and in the two decades since.

As Anthony put it, “Twenty years later, Emily is still the best thing that happened that day, as that’s when Joy entered my world.”