Elaine Feagan thought she was going to die, so she went looking for two people she considered her reasons for being alive.

One was the 12-year-old Tucson boy who gave her CPR and saved her from drowning in 1963, when she was just 19 months old.

The other was a 22-year-old University of Arizona student Elaine kept from bleeding to death in 1992, after he crashed his car on Interstate 10 north of Tucson.

For a long time, she never saw much of a connection between the two events. They lived in her mind as separate traumas.

Then she got sick.

About a year ago, the 60-year-old Oracle woman developed acute diverticulitis and unexplained problems with her liver and her pancreas that left her wracked with pain and unable to eat. While doctors struggled to diagnose her, she shed 40 pounds from her already slender frame.

By March, she weighed just 105 pounds and was talking to her four daughters about a will and funeral arrangements.

“There was about an eight-week period that I, honest to God, did not know if I was living or if I was dying,” Elaine said.

Suddenly, she couldn’t stop thinking about the young man she had saved on the highway that night almost 30 years ago. Suddenly, she needed to know everything she could about how — if not why — she had been saved when she was a toddler.

“I guess I had the idea that I was about to meet my maker. Before I went, I had some holes in my life I needed filled in,” she said. “It was a total chain of events that pretty much started with my drowning. Somehow, my survival early on made everything possible.”

Except surviving is rarely so simple. And sometimes searching for answers means sifting through pain.

On June 18, 1963, little Elaine Feagan got a second chance at life.

Her sister, Dena, did not.

The crash

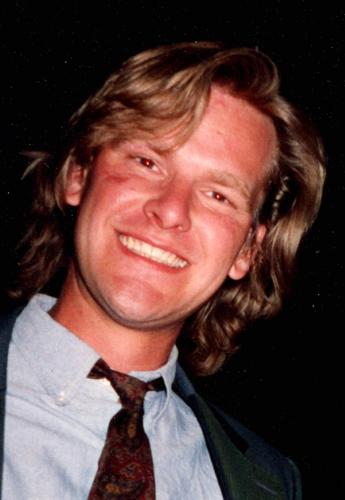

On Aug. 21, 1992, Chad Galts had just started his second year of graduate school at the University of Arizona, where he was studying English and working as a teaching assistant.

He got up that Friday at about 5 a.m. and went for a run before his first day of teaching classes.

Then, after work, he went to a bar and drank himself into a bad idea. He decided he would drive to Phoenix late that night to meet up with some friends from high school.

As a UA graduate student in spring of 1993, Chad Galts was still struggling with symptoms from a head injury suffered months earlier in a near-fatal crash on I-10. "Something really awful happened to me, and I kind of did it to myself."

So after a long day and a festive evening, the 6-foot-4 aspiring novelist squeezed himself behind the wheel of his shiny orange 1969 Datsun 510 and headed north. He didn’t bother putting on his seatbelt.

“I remember getting on the highway probably around midnight, and waking up in intensive care the next day,” Chad said. “I can’t remember the accident at all.”

Elaine saw the whole thing.

At the time, she was living in Tooele, Utah, about 35 miles southwest of Salt Lake City. That night, she was headed south on I-10, in the last hour of a long drive to Tucson to attend her grandmother’s funeral.

“I had two sleeping babies and a sleeping boyfriend in the car. We were going this way. He was going that way,” she said.

As the two cars approached each other in the dark somewhere between Red Rock and the exit for Pinal Airpark, Elaine saw Chad’s car veer off the road, swerve back sharply and overturn.

“Instead of a traditional roll, his car cartwheeled,” she said. “And as it came down on the last and final roll, he came out the window.”

Elaine remembers hitting the brakes and steering through the center median to get to the other side of the highway.

Chad was a mess when she got to him.

The crash tore up the right side of his face, ripped off part of his right ear and screwed up his teeth. He also had a broken rib and numerous lacerations, including a gash running at least 6 inches along his scalp.

“My head took the brunt of it,” Chad said. “I had the concussion to end all concussions.”

Elaine’s boyfriend brought her a pair of her sweatpants, and she wrapped them around Chad’s head to control the bleeding.

Chad Galts' Datsun 510 "cartwheeled" north of Tucson in the early morning hours of Aug. 22, 1992, says Elaine Feagan, who saw him fly out the window. She wrapped his head to control the bleeding and tried to keep him from losing consciousness.

Then she talked to him to try to keep him conscious. She got him to tell her his name, where he was from, where he’d been trying to go.

“Every time he looked like he was starting to fade off and his eyes would start to roll, I’d tell him, ‘Chad, come back. I love you,’” Elaine recalled with a grin. “What young college man doesn’t go, ‘What?!’ when a woman says I love you? You’ve got to pull out all your cards in a moment like that. I had to keep him awake and with me.”

Minutes passed before another vehicle came by, but eventually someone else stopped and flagged down a truck driver, who used his radio to call for help.

Chad was packed into a helicopter at the scene and flown to Tucson Medical Center, though he doesn’t remember that part, either. Not even the invoice he later got from the air ambulance company was enough to jog his memory.

“It was a big bill, and I didn’t have any money,” he said. “I was a grad student in English for Christ’s sake. Of course I didn’t have any money.”

A day or two after the wreck, Elaine went to see Chad in the hospital. She said she needed to know for certain that he had made it.

The police officers at the scene had given teddy bears to her two young daughters to comfort them, so she gave one of the bears to Chad, along with her name.

Chad Galts kept the teddy bear Elaine Feagan gave him in the hospital in 1992. Here it sits next to a Galts family photo from 1970, when Chad was a baby in his mother’s lap.

He was still in a fog of head trauma and pain medication, so the significance of her visit was lost on him at first.

“She was a real babe. I remember that,” Chad said with a laugh. “I didn’t know that I’d be dead if she hadn’t stopped. That came to me later. People in the hospital told me.”

He spent five days at TMC and about a week at his parents’ house in Phoenix, before returning to work and his studies at the UA.

“I had to teach classes,” Chad said.

For the next six months, though, he struggled with lingering symptoms from his head injury, including horrible mood swings, flashes of rage and an inability to focus. Dizzy spells made it difficult for him to keep his balance.

“I walked with a cane for a while, and I looked awful,” he said. “That was a tough time, mostly mentally. Something really awful happened to me, and I kind of did it to myself.”

Still, he managed to earn his graduate degree. He left Arizona the summer after his accident and moved to Rhode Island the summer after that. He has lived there ever since.

Chad Galts, his wife, Mary Beth Meehan, and their sons, Graham, left, and Edward, at Edward's eighth grade graduation on June 10, 2020. That also happened to be Chad and Mary Beth's 20th wedding anniversary.

“I got married, had kids, bought a house — all the things you would expect,” Chad said. “If I’m going to be honest, I’ve had an incredible run of good luck. And the only reason for any of it is because of what (Elaine) did.”

The pool

The Feagan family rarely spoke about the drowning.

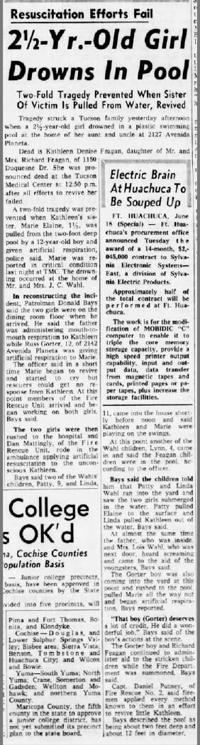

Much of what Elaine now knows about it comes from a front-page story that appeared in the Arizona Daily Star on June 19, 1963.

“Tragedy struck a Tucson family yesterday afternoon,” the story begins.

At the time, Richard and Eva Feagan were living with their two young daughters in an east-side neighborhood across 22nd Street from the newly opened Palo Verde High School.

Richard’s aunt and uncle, John and Lois Wahl, lived a little over a mile away with their kids.

John Wahl was serving in the Air Force in France at the time, so Richard went to their house that day to work on his aunt’s car. He took 2½-year-old Dena and 19-month-old Elaine along with him to give his wife a break.

It’s unclear how the two girls wound up in the small above-ground pool in the backyard or for how long, but it was the Wahl children who found them submerged there.

According to the newspaper account, the girls were pulled from the water by their cousins, Linda, 11, and Patty, 9, and a 12-year-old boy from down the street named Russ Gorter.

Richard and Lois came running when they heard the children screaming.

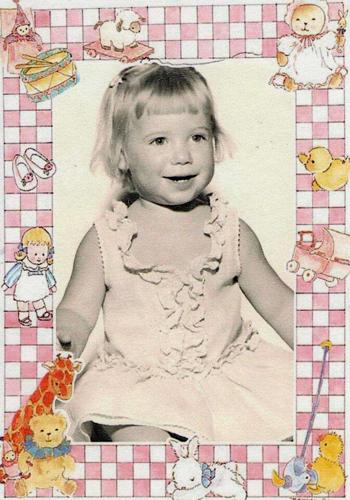

Kathleen Denise Feagan, better known as Dena, was 2½ years old when she drowned. In the years that followed, her parents would rarely speak about the accident, and her younger sister learned not to press them.

When police officers arrived, they found the two girls sprawled out on the dining room floor, with Richard giving mouth-to-mouth to Dena and Russ Gorter working on Elaine.

“That boy deserves a lot of credit,” Tucson police patrolman Donald Bays told the Star later that day. “He did a wonderful job.”

The girls were rushed to Tucson Medical Center, where Dena was pronounced dead.

Elaine clung to life, but she’d gone so long without oxygen that doctors worried about permanent brain damage.

“I was dead for so long, they had to slice my leg open to get fluids in me,” she said, pointing to the scar. “They had to cut my leg open, because my veins had collapsed.”

Elaine still recalls vivid flashes she insists are from that day — impossible-seeming memories for someone who was as young as she was at the time.

“I seem to remember being placed in the water. I have no idea who it was,” she said. “I remember the slick feel of the bottom of the pool. I remember my feet coming out from under me.”

She said she also remembers waking up in the hospital and seeing a woman’s face through the square metal frame of the bed or crib she was in. “She had short dark hair and a white hat. I’m assuming that was the nurse,” she said.

Elaine has always had lingering questions about that day, but she said as long as her parents were alive, she didn’t press for answers from them or anyone else in her family.

“I remember asking my mother once about a picture of my sister, and my mom started to cry, so I just never really touched on it again,” she said.

Less than a year after Dena’s death, the Feagans abruptly moved to the San Francisco Bay Area.

Richard and Eva Feagan pose with daughter Elaine not long after her big sister, Dena, drowned in a backyard pool in Tucson in 1963.

Before they left, Elaine said, her father boxed up all of her sister’s things and put them in the attic of their house in Tucson.

“And if I’m not mistaken, when we moved to California, they left (the boxes) there. It was that horrific and that painful for my parents,” she said.

Elaine’s two younger sisters were both born in California, but the family eventually returned to Arizona when Elaine was in the second grade.

After they moved back, Elaine said, she used to go with her mother and grandmothers to place flowers on her sister’s grave in “babyland” at South Lawn Cemetery, usually around Dena’s birthday in early December.

She said her mother never entirely got over losing Dena and her father never forgave himself for it, though the two of them stayed devoted to each other until his death in 2004.

“My mom did not step foot into a church until probably the year before she passed away” in 2011, Elaine said. “She wasn’t mad at my dad. She wasn’t mad at my cousins. She was mad at God.”

The little girl’s death also weighed heavily on the Wahl family.

According to Linda Wahl, her mother, Lois, nearly had a nervous breakdown.

Her father was immediately sent home from France on hardship leave. He wrote a poem about his great-niece Dena that he read at her funeral.

Linda was just 11 the day it happened, but she said she felt like her mother never stopped blaming her for her cousin’s drowning.

“It took a toll on my (whole) relationship with my mom,” Linda said. “I always felt like my mother was angry at me. She never said anything to me, but I just felt it.”

For a long time, Linda felt responsible, too. After all, she clearly remembers being inside the house that morning, watching cartoons with her siblings, when her mom told her to keep an eye on Dena and Elaine.

The South Lawn Cemetery marker for toddler Dena Feagan, who drowned in 1963.

“I carried that my whole life. It was devastating,” she said.

In recent years, though, she has come to believe that her two little cousins were already alone in the backyard, maybe already in the water, by the time she was asked to keep track of them. What felt like blame from her mother was actually just guilt. The person Lois Wahl was truly angry at was herself.

“All my life I lived with the fact that they were in the house and they got away from me, but they were never in the house,” Linda said with conviction, 58 years after the fact. “I never saw the girls until I saw them in the pool.”

It wasn’t the last tragedy the Wahls would have to endure.

Six years after the drowning, on Thanksgiving Day 1969, Linda’s big brother, Army Spec. Mickey Wahl, was killed in action in Vietnam.

A short time later, her parents sold their place on the east side and moved to a quiet spot in St. David.

“They wanted to get out of Tucson. It was too much for them,” Linda said. “My mom and dad went through the wringer in that house. We figured that house was cursed.”

The saved

Once Elaine started looking, Chad Galts was easy enough to find.

She quickly came across a man with that name on Facebook who lived in Rhode Island but had the UA in his profile. The face in the photos looked vaguely familiar, so in mid-February she sent him a message asking if he had been in an accident in 1992.

She didn’t hear back from him until late March, when he logged onto Facebook for the first time in months.

Chad, who works as a communications director with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, was in the middle of a 50-person virtual meeting when he finally saw Elaine’s Facebook Messenger notification on his laptop.

He knew who it was right away. He still had the teddy bear she’d given him.

“I’m looking at this message, and I’m like, ‘Holy shit!’ and then it’s my turn to talk in this Zoom meeting,” he said. “It was this incredible bolt of lightning that made it hard to pay attention to work.”

Chad had never forgotten Elaine, and in the decades since the accident, he has seen to it that others knew about her, too.

His two sons, now 18 and 16, have heard the tale more than most.

Chad Galts and Elaine Feagan reunited at an Oracle restaurant in June. Chad brought along his sons, Graham, top, and Edward, who had long heard tales about their dad's savior. "If you had not been where you were that night, I would not be sitting here," the younger boy told her. Said Elainie: "That was pretty profound, coming from a teenager."

“It’s a story I like to tell (called) ‘This is the best that you can be,’” he said. “What you do matters. Talk is great, and it’s great to say the right things, but your actions are what’s really important.”

Chad tried to track Elaine down a few times over the years. When Facebook came along, he would look her up once a year or so, but all he had to go on was her married name and the town in Utah where she had been living. By then, Elaine was divorced and back in Arizona.

After reconnecting earlier this year, the two exchanged phone numbers and a few text messages before scheduling their first call.

“We talked for about 4½ hours,” he said.

“I needed to know from Chad, ‘Did you have kids? Did you have a good life? Did you move past your accident and just do things?’” Elaine said. “I don’t know why it was so important to me. It just seemed like a circle that needed to come all the way around.”

They soon made plans to reunite in person at a restaurant in Oracle on June 22, while Chad and his sons were in Scottsdale to visit his mother.

On the way there that day, Chad pulled over along I-10 to show his kids the place where he almost died. He said he remembered just where it was because he’d stopped there about a decade ago and found a windshield wiper from his old Datsun.

“The boys were very interested in where it happened,” he said. “This wasn’t just some trip.”

Meanwhile, Elaine was having a minor epiphany of her own on her way to meet Chad. “It hit me as I was leaving my driveway: I have no idea how tall this man is,” she said.

The only other times she had seen him, he’d been lying down — first bloodied on the ground and later in a hospital bed.

“He got out of his car (in Oracle), and it was like he just kept getting out of his car,” Elaine said. “We gave each other a great big hug, and he was shaking as much as I was shaking. This was, I think, a very important moment for both of us.”

Chad laughs when he recalls one of the first things she said to him when they saw each other face to face: “‘I just wanted to make sure you weren’t a serial killer.’”

He said his sons were “just kind of in awe,” like they were meeting a character from a bedtime story they had been hearing since they were little.

They gave her a bouquet of flowers, and the four of them talked in front of the restaurant for hours.

“I think what struck me is that these boys have known my name their whole lives,” Elaine said. “The younger of the two looked at me point blank and said, ‘You do know, if you had not been where you were that night, I would not be sitting here.’ That was pretty profound, coming from a teenager.”

They’re already making plans for their next get-together, probably sometime around Christmas.

Elaine said she can’t wait to meet Chad’s wife, Mary Beth Meehan, an accomplished artist and photographer. She can’t wait to introduce the Galts to her daughters — her “apples,” as she calls them — and the 10 grandchildren they have given her.

Elaine Feagan, second from left, and her four daughters, whom she calls her "apples." They are, from left: Aubrie Bush, Jessika Bush, Savhana Bush and Mackenzie McWhorter.

Chad is looking forward to it, too, though it all feels a little surreal.

“I haven’t quite figured out what my relationship with Elaine is going to be. I have a lot of family in Arizona, and now I have Elaine. She will be part of the routine when I come to visit,” he said.

“I sometimes wonder what it must be like to be her and have this person out there who owes you everything,” Chad said. “She’s a remarkable character. I can’t believe that of all the people who were going south as I was going north in the middle of the night, it was her.”

The saviors

Elaine will have to live without an emotional reunion with her own savior.

It seems Russ Gorter, now in his early 70s, isn’t interested in revisiting the past.

Elaine launched her search for him in January by posting the old newspaper story about the drowning on a Facebook page for longtime Tucsonans.

She also worked on her own to find Gorter and others mentioned in the article, and she recruited a few internet sleuths to do the same.

It marked the first time she had sought out the people who were there to help her 58 years ago.

In the process, Elaine reconnected with a few family members she had lost touch with, including Linda Wahl and another cousin who recalled overhearing at the hospital that both little girls had been pronounced dead at some point.

Elaine eventually tracked down contact information for Gorter, but she received no response to the email she sent him a few days after her reunion with Chad.

She later learned through Gorter’s sister, Christina Cure, that he went from preteen hero to U.S. Navy medic, and then worked as an EMT and an ICU nurse in Ohio.

Cure made it clear that her brother does not want to be contacted about that day in 1963 or anything else.

“He’s a very private person,” Cure told the Star, after Gorter did not respond to a phone message from the paper. “He would be mad at me for even talking to you.”

Elaine was hoping for a different answer, but she intends to honor Gorter’s wishes.

“I wanted to thank him and let him know that because of (his) heroic actions that day, I have this beautiful family. I’ve got these amazing grandchildren. I was able to help Chad, and he has these beautiful children and this wonderful life,” she said. “It all came back to that one moment of bravery — for that 12-year-old young man to have it in him to step up and help, whatever the circumstances were at that moment.

“As a direct result of that, all of this other wonderful stuff has happened,” she said. “The song just goes on and on and on and on, and we can trace it all back to that one day.”

Elaine hasn’t given up completely. She still hopes to learn more about the day she lost her sister and almost drowned. After all, there are still more family members to talk to and more people to track down from that old newspaper story.

Lucky for her, she no longer needs to hurry. It turns out Elaine isn’t dying after all.

By the time the doctors figured out what was wrong with her, she was already starting to get better. Now she’s slowly gaining back the weight she lost and feeling less like someone whose days are numbered.

If anyone knows what to do with borrowed time, it’s Elaine Feagan.

“According to everything I know, I should not be sitting here. And yet, here I am,” she said, reflecting on her near-death experience as a child. “The universe has seen to it to put me in a lot of very convenient locations throughout my life. I’d like to believe that I’ve been where I was supposed to be.”