It doesn’t matter legally whether the land where the Rosemont Mine’s tailings and waste rock would go has valid mining claims, say attorneys for the mining company and for the U.S. government.

They say that anywhere on the mine site in the Santa Rita Mountains is OK to put the wastes as long as that land is otherwise legally “open” to mining.

But mine opponents say federal law and past court cases make it clear that valid mining claims and valuable minerals must be present on land where mine wastes would go.

Scientists are putting efforts into helping devastated forests come back to life. They're planting native trees in forests that have been destroyed. The military is also helping in stopping people from illegal gold mining.

To make their case, they cite the 1872 Mining Law, which opens federal lands to mining — if a miner or prospector has a valid claim.

Now, a federal three-judge panel in the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals must decide who is right. The case’s outcome could set a national precedent, legal experts have said.

The judges asked plenty of questions at a recent hearing via Zoom transmission.

Hudbay Minerals Inc. and the U.S. Justice Department want the 9th Circuit to overturn a July 2019 ruling by a U.S. district judge in Tucson who stopped mine construction the evening before it was supposed to begin.

District Judge James Soto faulted the U.S. Forest Service for failing to show that Hudbay had valid mining claims or valuable mineral deposits on 2,447 acres slated for waste disposal in the Coronado National Forest.

Judge William Fletcher, an appointee of former President Bill Clinton, grilled attorneys for Hudbay and the government at the hearing, often expressing skepticism of their views.

Judge Danielle Hunsaker, an appointee of just-departed President Donald Trump, used equal skepticism in questioning attorneys for tribes and environmental groups suing to stop the mine.

The third judge on the panel, Eric Miller, also a Trump appointee, said relatively little compared to the other judges.

The precedent-setting nature of this case was underscored by the fact that neither side’s attorneys, under questioning from judges, could cite an instance in which an individual mine was either required or not required to put wastes on land with valid claims and valuable minerals.

The judges did not indicate when they will rule.

Hudbay’s and government’s side

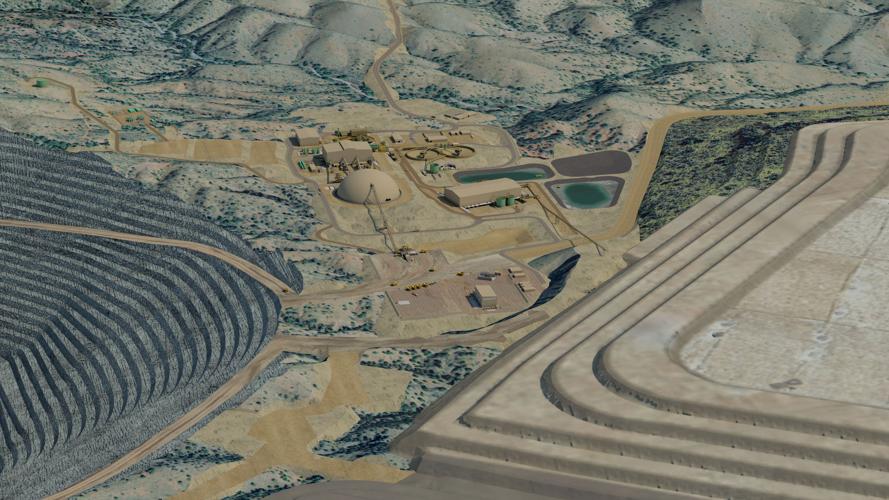

Soto ruled the Forest Service had accepted without question the validity of mining claims where Hudbay plans to put 1.9 billion tons of waste in the Santa Ritas southeast of Tucson.

Despite the 1872 law’s requirements for valuable mineral deposits and valid mining claims, Soto wrote that Forest Service records reflect no location of a valuable mineral deposit on those 2,447 acres.

But at this month’s hearing, Hudbay and Justice Department attorneys argued that all that’s needed is for valid mining claims and mineral deposits to exist on the entire mine site — not on the waste disposal area.

They argued that mine opponents were trying to get this land barred to mineral entry, after Congress has repeatedly refused to do that.

The claims don’t have be on “the particular particles of soil or square inches of soil directly under where waste rock and tailings are to be stored,” Hudbay attorney Julian Poon said. “As long as the lands, writ large, as long as they generally qualify as mineral lands other than agricultural lands, that’s sufficient.”

He used the legal term “writ large” to refer to historical decisions leading to the creation of the Rosemont and Helvetia Mining Districts in the Santa Ritas in the 19th century.

Poon noted that the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, which makes final decisions on claim validity, has said a validity exam for a mining claim costs anywhere from $12,000 to $80,000 per claim.

The BLM wrote in 2007 that the cost of conducting validity exams for all 250,000 mining claims filed in the U.S. would exceed the bureau’s annual operating budget “many times over.”

Environmentalists’ and tribes’ side

Attorneys representing opponents — including six environmental groups and three tribes — said the 1872 law makes it clear that a valid mineral deposit has to lie on federal land for someone to occupy it for mining purposes, including putting wastes there.

Numerous federal court rulings have reached the same conclusion, they said.

Environmentalist attorney Roger Flynn also cited the 1955 U.S. Common Varieties Act, which he said barred companies from filing mining claims on land containing ordinary rock and stone.

Soto’s ruling said geological studies and geological maps in the record “indicate there is primarily common sand, stone, and gravel beneath the land at issue.”

“The problem is that the Rosemont’s mine’s ... proposal to put tailings and waste on federal property doesn’t respect limits of the general mining law,” said Heidi McIntosh, representing the Tohono O’Odham Nation and the Pascua Yaqui and Hopi tribes.

“The Forest Service ignored the plain meaning and terms in the statute that requires a valuable mineral deposit,” she said.

“What we are talking about here are lands where tribes have a 10,000-year history. Their ancestors are buried on this site,” McIntosh said. “There are sacred springs and other sites that are important to their cultural tradition. There are village sites and other cultural sites that will be obliterated if the plan goes forward as Rosemont would like to do.”

Judge’s questions for company

Fletcher questioned the company and government view that valid claims aren’t needed.

“For the government to say that these are invalid claims but that nonetheless we will allow the operator to deposit an enormous amount of waste rock and tailings on them, I don’t see how the government can get there,” Fletcher told the Justice Department’s Amelia Yowell.

Yowell replied that since these lands are open to anyone to explore under the 1872 law, for the feds to investigate the claims’ validity would be an empty exercise. If one claimant’s claims were found invalid, someone else could come back and file another claim, she said.

It’s undisputed that Rosemont has a large, valuable copper deposit, and that Rosemont has the right to mine it, Yowell said. “It’s also an undisputed fact they have got to have a place to store waste rock and tailings.

“If they couldn’t store waste rock and tailings there, that would in effect prohibit Rosemont from exercising its right under the mining law to mine this valuable deposit.”

Judges’ questions for mine opponents

On the other side, Hunsaker told McIntosh that she’s struggling with opponents’ arguments, saying, “If our purpose and our policy is to explore and utilize valuable minerals, why would we make a system where you have to pile waste right on top of something that could be valuable?”

Each mining claim that’s staked on the ground is about 15 football fields big, McIntosh replied.

That’s plenty of room to accommodate both mineral extraction and for other purposes like the disposal of mine wastes, she said.

McIntosh and Flynn also said the company has alternatives to dumping wastes on federal land lacking valid mining claims. It could file what’s known as “millsite claims” to occupy land without valuable minerals, they said.

The company could also propose a land exchange to get land legally suitable for mine wastes. Or, Hudbay could purchase land elsewhere for that, McIntosh said.

Local thoughts on the Rosemont Mine from 2019:

Your opinion: Local thoughts on the Rosemont Mine

Letter: Rosemont is short-sighted

UpdatedOn one hand, Colorado River basin states struggle to apportion the river’s water to a region whose climate future foretells warmer temperatures and drought. Water is our future.

On the other hand, Rosemont Copper is receiving a green light to devastate fresh water resources for a mine with a 20-year production span. The carrot of jobs will be followed by the stick as they disappear. Our eco-tourism industry will be damaged, our water polluted.

The Star’s Mine Tales series featured quaint stories of historic mines. Each had a short life that lives on in relics they left behind. This mine will be different only in the scope and toxicity of its debris.

We should not be tempted to sell our future for such short-sighted pennies. Twenty years: our children are not even allowed to drink alcohol legally by this age. Do we forget how quickly they grow up, and how valuable is their future?

Katy Brown

Midtown

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Permitting Rosemont Mine is wrong

UpdatedThe permitting of Rosemont Mine is a Death of Many Dreams - dreams of defending our public lands for the welfare of the public, of preserving rare birds and wildlife and the pristine natural areas they inhabit, of maintaining natural watersheds and clean ground water resources for all living beings, of living in a Democratic society where the people have control over their fate, and of a government that supports and protects our local tourist economy rather than permitting it to be destroyed.

After 20-plus years of constant destruction, noise, and pollution, the Santa Rita Valley will be left with a vast chemical “lake,” 1/2 mile deep and 1 mile wide, surrounded by 4,000 acres of enormous rubble fields that will, allegedly, drain water from this area forever. For a preview, look into the massive environmental impact that Hudbay Minerals has created in Manitoba and Peru.

Whatever laws or traditions or thought processes permit this devastation MUST BE CHANGED! This is WRONG. Paradise lost.

Peggy Hendrickson

Green Valley

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Where is the outcry/protest to the Rosemont Mine?

UpdatedTake a good look at the jaguar picture in the 3/13 paper --it may be the last jaguar we ever see in AZ. The ocelots will also be gone and what other wildlife?

The Santa Ritas are the most beautiful of the mountains surrounding Tucson. Having camped there some years ago, near a running stream, I saw several deer and eight coatimundis in single file, tails held high, walk thru our camp. The drives all around there are scenic and beautiful. Once the mine goes in, the natural beauty, clear water and wildlife will disappear. Why are there no protesters demonstrating against this destruction? Living in Madison WI in the 60's, I was one of hundreds of protesters who came out for causes with great impact. Do we want destruction and ugliness in place of natural beauty? Do your part to stop this mine!

Jacque Ramsey

Oro Valley

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: rosemont mine

UpdatedMort Rosenblums recent article on the proposed Rosemont mine was insightful. His measure of tourism vs. mine revenues indicates that tourism creates a more sustainable stream of revenue for the state. If the mine were to be built, this beautiful and pristine place would be gone. The majority of the copper and its revenues would go to foreign countries and the resulting blight would be ours forever. Our water resources would be vulnerable. My husband and I live 12 miles from the proposed mine and wonder what it would be like with trucks rumbling up and down scenic highway 82 all day. I hope the voice of the people will be heard and the EPA will veto the permit.

Joan Pevarnik

Vail

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Rosemont Mine

Updatedin response to "Mort Rosenblum: The true cost of Rosemont mine", I think we need to realize that rather than reducing tourism, the mine will actually INCREASE visitor spending as vendors, and others flock to the mine to do business with them. Tourist will come to SEE the mine, as they have to many mines around the country. the mine is not going to destroy the desert and beauty that surround Tuscon. Sorry Chicken Little, but the Sky is NOT FALLING. The same people want to decry the mine turn around and support "green" energy. They do not realize that to supply the needed copper for wind turbines and electric vehicles do not realize that the "Green New Deal" would require a DOUBLING of world copper production, just to meet the USA demands for copper. Come on people, let's be real and realize the real benefits of the mine. It is time to stop obstructing and start benefiting.

Marty Col

Downtown

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: What Jaguars

Updated“Rosemont would do devastating damage to Arizona’s water and wildlife. We’ll fight with everything we have to protect Tucson’s water supply, Arizona’s jaguars and the beautiful wildlands that sustain us all.” Randy Serraglio, Center for Biological Diversity

What jaguars? Arizona doesn't have any jaguars. Very rarely we see one that's a visitor from Mexico. These objections to mining and walls would have more credibility if they weren't so often filled with egregious hyperbole.

Jim McManus

East side

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Proposed Rosemont Mine

UpdatedState highway 83 is the only road accessible to the proposed huge open pit mine called Rosemont. From the Rosemont road intersection with the highway 83 driving North to the Interstate 10, the road lanes are dangerously narrow for a 4 mile section to milepost 50. The highway lanes narrow to 8.5 feet in each direction and along the way steel guard rails are 1 foot from the right white line. No pull off and windy narrow roads could result in dangerous driving conditions especially in sharing with large rock haulers from the mine. I think ADOT allowed a road usage permit in error and I can envision litigation “down the road “.

Hank Wacker

Sonoita

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Rosemont Mine

UpdatedIn his excellent piece of March 10, Rosemont go-ahead casts aside EPA fears over Water, Reporter Tony Davis reports that The Army Corps of Engineers has issued the final permit required for the Rosemont Mine Project over the strong objections of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The Rosemont Project was ill- conceived from its very inception, and represents yet another desecrating assault on our shared and essential habitat. In this era of drought and looming water shortages, Rosemont makes absolutely no sense, even for the shareholders of the Hudbay Corporation, its Canadian-based developer. To justify it decision, the Army Corps states repeatedly that Rosemont will only affect 13% of the watershed. If I drink a glass of water that is 87% clean, but 13% has cyanide in it, the result will be deadly. We have to wake up the reality of our finite resources and their fragility before it is too late.

Greg Hart

Midtown

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Rosemont Mine

UpdatedRe: “Rosemont go-ahead casts aside EPA fears over water”

President Trump is probably the only power who can stop the Rosemont Mine. Please contact him.

David Ray

Midtown

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Rosemont Mine Sellout

UpdatedDrive a few hours east to Morenci, Arizona and look at one of the world's largest open-pit copper mine with reserves of 3.2 billion tons. I was raised in this town and know first hand about environmental devastation. This man-made destruction is visible from our space station. Someday, the Rosemont mine will closely resemble Morenci. The water, toxic waste, and wildlife issues have been studied and ignored. Supporters argue that we need more copper, but don't tell you that worldwide there is no shortage. Chile, Peru, China, Mexico, and Indonesia are the world's top copper producers and it is said nearly 6 trillion tons of estimated copper resources exist. US Geological surveys show there are approximately 200 years of unclaimed resources are available. In addition, nearly 80% of all copper mined is recycled. So we will have more jobs and more tax revenue, but this beautiful wilderness will cease to exist. When it's gone, it's gone. Once again, greed and the mighty dollar triumph over our environment.

Judy Bullington

West side

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Saving the San Pedro River

UpdatedTwo environmental issues critical to southern Arizona have been awaiting decisions by the Army Corps of Engineers, Rosemont Mine and the Villages at Vigneto development near Benson. On Friday, the Army Corps issued a permit that allows the mine operation to begin.

Rep. Raul Grijalva and Rep. Ann Kirkpatrick together made a last minute plea to the Army Corps to reconsider its impending approval of Rosemont. Now their unified voice is needed to request that the Army Corps give adequate consideration to reinstating a permit to allow the 28,000 home Villages at Vigneto to proceed near the San Pedro River. This proposed mega-city will threaten the vital streamflow and riparian habitat of the San Pedro.

If our representatives speak out now, maybe at least one of two environmental nightmares can be avoided.

Debbie Collazo

West side

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Rosemont Mine

UpdatedRosemont Mine has finally been given the OK to build the mine in the Santa Rita Mountains. According to reports, the copper there will take about 20 years to extract. If a person goes to work there at the age of 20 or 25, when the mine closes they will be out of work with still half of their work life ahead of them and they will need to relocate to continue their mining career. So after only 20 years, Tucson will lose 500 good paying jobs and be left with a huge scar on the mountain and the degradation of an ecosystem that may never recover. Is it worth it? I think not.

Sandra Hays

Northwest side

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Looking forward to the economic boost of the Rosemont mine

UpdatedI am very pleased to read that the US Army Corps of Engineers has given final approval to the construction of the Rosemont mine.

I have long supported Rosemont for its significant contribution to the economic development of Southern Arizona and for its wise use of the copper resources that our Creator - sorry, atheists, not - bestowed upon our part of the globe.

I too have an interest in the environment but not to the extent of preventing the sound, environmentally-respectful development of this mine. I make my living teaching via computer and telecommunications, and they needed copper to be built and run. So do many other things that I use.

As for the American Indians / Native Americans who protest, they should be thankful that Rosemont will benefit them too if they take advantage of its work opportunities, plus the increased tax revenues will make it a little easier for the government to fund the highly-subsidized reservation system for those who choose not to assimilate into broader American society.

James Stewart

Foothills

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: The Cost and Legacy of Tainted water ??

UpdatedA month ago, you ran a Business article ( Rimini, Montana 2/21/19) on the unspeakable outrage of Mining legacies that poison and taint long after mines are abandoned. The state of Arizona and the United States permit this contamination for unfathomable reasons.

It is not a secret and is a nation-wide and world-wide travesty. Why - is this allowed ? Who agrees to allow it and even invite other nations to purchase precious land and metals for their own profit ? How long does arsenic, lead , zinc and worse continue to contaminate the water, wells, streams and land once poisoned ? To quote the above article: “ the waste is captured or treated in a costly effort that will need to carry on indefinitely , for perhaps thousands of years often with little hope . ..”

When, Who, How and What will it take for Arizona and Pima county STOP the Rosemont Mine ?

Please, the cost of too high !

Susanne Burke-Zike

Oro Valley

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Where's the outcry?

UpdatedWith our water supply threatened by overpopulation and global warming and Lake Mead looking like a half-drained bathtub, comes the news that Rosemont Mine will be approved. The 75,000 trees and the beauty of the mountain will be destroyed. The precious water will be polluted despite the denials of the "experts." Look at water supplies around the country that have been/are being polluted by mines. And this is for a FOREIGN COUNTRY to sell copper to a FOREIGN COUNTRY.

Where is the outcry? Where are the mayors of Tucson, Sierra Vista, and Green Valley, senators, representatives, City Council, and Daily Star editors? We once marched against the Iraq war, and look what happened. As Shakespeare said, "What fools we mortals be!" Or Pogo: "We've met the enemy, and it is us."

Diane Stephenson

Foothills

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Questioning the Corps of Engineers

UpdatedThe U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is a law unto itself. Some years ago, The Atlantic ran an article, "The Public Be Dammed," on the Corps, and it has been damming and damning before and since.

For over 90 years the Corps has been responsible for dams and navigable rivers, yet the floods and flooding continue. Why? Because the Corps is rewarded with funding to clean up the mess it was responsible for. The flooding of New Orleans, for which the Corps was entirely responsible, cost about one billion dollars. The National Review commented, "Never has incompetence been so richly rewarded." It should come as no surprise for the Corps to allow the construction of the Rosemont Mine.

Andrew Rutter

Midtown

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Rosemont Mine

UpdatedThe ASARCO Mission Mine South of Tucson is located COMPLETELY within the Tohono O'Odham Indian reservation; I worked there for 12 years and as a heavy truck driver, we would go from the main pit to the San Xavier North pit, a distance of 2-3 miles . Many times I would see deer, bobcats, javelina, rabbits, wild horses, etc. on the road . At the San Xavier North pit, there was a water pipe stand water trucks would use to fill the 10,000 gallon water trucks, and the overspill would fill a small waterhole that wild horses would use to drink. Many workers would want to buy wild horses from the Tribe but would be told they were not for sale. Now all of a sudden the Tohono O'Odham and other tribes are against the Rosemont Mine!!?? All wild life in that area to the trucks, etc. No different in this case

Hector Montano

South side

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Copper vs water

UpdatedIt will be a sad day in Arizona should Toronto-based Hudbay Minerals Inc. receive approval for the Rosemont Mine. The critical issue is the value of copper over water. We can live without more copper. Clean water, however, is necessary for survival. Water is more precious than any mineral the mine can extract.

Hudbay is just another foreign-based company robbing Arizona of its natural resources. Long after Hudbay has finished raping the land, polluting the water and air, our children will be left with their mess. I predict in 50 years the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and EPA will collectively wring their hands and bemoan, “What were we thinking?"

Robert Lundin

Green Valley

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Ann Kirkpatrick, Raul Grijalva: Anti-Capitalists

UpdatedNew District 2 Congresswoman, Democrat Ann Kirkpatrick, and District 3 Congressman, Democrat Raul Grijalva, are anti-capitalists. The Star (3/1/19) reports they are against development of the Rosemont copper property 30 miles southeast of Tucson.

Their contrariness puzzles, for they serve citizens of Cochise, Pima, and Santa Cruz counties who will benefit hugely from Rosemont. An assessment by ASU’s W.P. Carey School of Business (2009) reports the operating mine will bring the counties 2100 jobs.

Annual revenues to counties will be $19 million; State, $32 million; Federal, $128 million. Surely, Pima County will pigeonhole its portion for road repair. Following reclamation, there are “lasting positive effects” for Arizona.

After a 12-year plod through steep EPA mining regulations and the hostility of no-growth enthusiasts, Rosemont is in the last phase of approval, finally.

Rosemont is a great example of capitalism that will wonderfully benefit so many families that these Representatives, oddly, oppose.

D Clarke

Sahuarita

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: Copper mining in the Santa Rita Mountains

UpdatedRe: the March 1 article "Grijalva: Rosemont Mine is on verge of final OK."

While Hudbay Minerals of Canada rapes our beloved Santa Rita Mountains, makes millions or more selling the copper and then pays our community a pittance of $135 million and provides 400 jobs until the mine is dead, we lose a pristine, unspoiled wilderness forever.

If claims were made that copper laid under the nave of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, would Hudbay crave it, too? Aren't the Santa Ritas as sacred? I beg you to pay attention and act against this travesty in any way you are able.

Jane Leonard

Oro Valley

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.

Letter: An alarming headline

UpdatedNo, not about Donald Trump, our lying, cheating, corrupt conman president, but the imminent approval of the Rosemont mine. In a time of acute drought, when Arizona has no real plan to deal with it, how is it possible that this project will be approved. The amount of water needed for this operation is absurd. This short term project with everlasting environmental devastation that will benefit ridiculously few, is, like Donald Trump, a real disaster.

Stanley Steik

Midtown

Disclaimer: As submitted to the Arizona Daily Star.