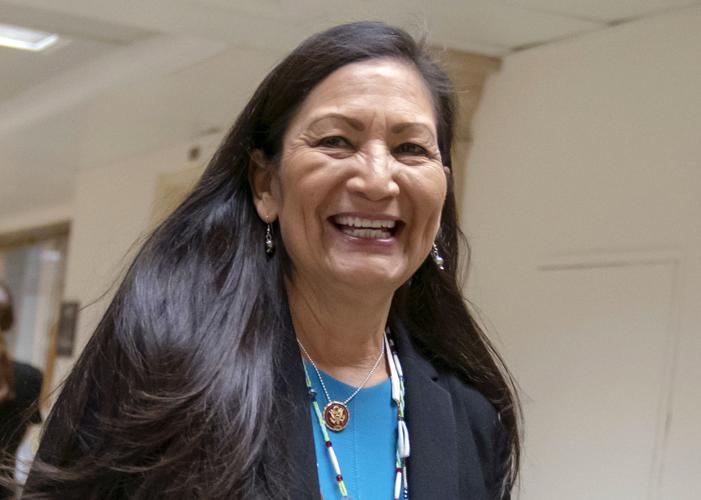

If U.S. Rep. Deborah Haaland is confirmed as interior secretary, the Native American from New Mexico could make a huge difference to Arizona and the West when her background and outlook are translated into policy.

Experts in Native American affairs and Democratic Party congressional leaders including Rep. Raúl Grijalva of Tucson and Sen. Tom Udall of New Mexico offer predictions for how Haaland’s tenure could affect federal lands and waters:

Water rights. Tribes have made a lot of legal headway in establishing claims to water rights, including those from the Tohono O’Odham, the Gila River Indian Community and several other Arizona tribes. But other claims are yet unfulfilled.

A federal study has estimated that in the Colorado River Basin alone, 1.2 million acre-feet of tribal water rights claims remain unsettled.

“We have so many rivers left still where Indian reserved rights have not been established. One way or another I’m sure she’s going to place a high priority on finishing those Winters rights off,” said University of Colorado law professor emeritus Charles Wilkinson, a longstanding expert on water rights and other Western issues.

He was referring to the Winters Doctrine that the U.S. Supreme Court established in 1908. It said the creation of Indian reservations implicitly reserved tribes’ rights to water to supply its reservations.

“It’s not a matter of advocacy. It’s a matter of what the Interior Department should be doing, given the consistent law recognizing tribal water rights. I think we can expect a really robust program to establish Indian water rights,” said Wilkinson, who has written numerous books on various Native American struggles as well as texts on Indian and federal public land law.

Speaking more broadly of the Colorado River, whose water supply has been declining because of climate change, Wilkinson said he expects Haaland to be a “plus” on resolving the myriad issues involving its management.

“The secretary’s convening powers are great. The key thing we need to do in the Colorado River watershed is to continue to get people in the same room and insist upon making progress. I think the new administration is going to be a very positive influence.”

Climate change. Haaland is one of six nominees by President-elect Joe Biden who will lead a governmentwide effort to push towards more renewable energy, “moving toward green power,” said outgoing Sen. Udall, a Tucson native.

The others include Environmental Protection Agency administrator nominee Michael Regan, climate envoy John Kerry, energy secretary nominee Jennifer Granholm, White House climate adviser Gina McCarthy and transportation secretary nominee Pete Buttigieg, Udall said.

The first effort Udall wants is action on what he calls “30-30” legislation, a so-far-unsuccessful effort that he and Haaland have sponsored to require the U.S. to protect 30% of all publicly owned lands and waters by 2030.

That would include those on the Outer Continental Shelf off the coasts.

It would involve restoring degraded federal lands as well as preserving more pristine lands, Udall said.

“It does two things. The healthier you get the soil, forests and ecosystems, the more they are a carbon sink, helping us fight the climate crisis,” Udall said.

“Second, we have a major extinction crisis, serious, serious problems; ‘30 by 30’ is protecting their habitat; returning us to the place where we’re part of the natural world, not just in an extractive situation,” he said.

But while grazing is one federal land use that could be affected by a 30-30 rule, a longtime Arizona cattle growers leader took issue with that.

“First of all I think that it’s safe to say that public-lands grazing is a part of our landscape. It should be part of any type of discussion, no matter who the secretary is, or where they want to go,” said Patrick Bray, executive vice president of the Arizona Farm and Ranch Group, which represents farmers and ranchers. “It’s an important part of our economy and our culture. Maybe it needs to be preserved.”

Beyond that, “the idea of preserving a certain percentage of our lands doesn’t make sense to me. We need to manage the landscapes so they are economically viable for the United States,” Bray said. “Preservation, in my mind, makes it about a museum. I don’t think we want to turn our public lands into a museum by any means. We want them active, vibrant and productive.”

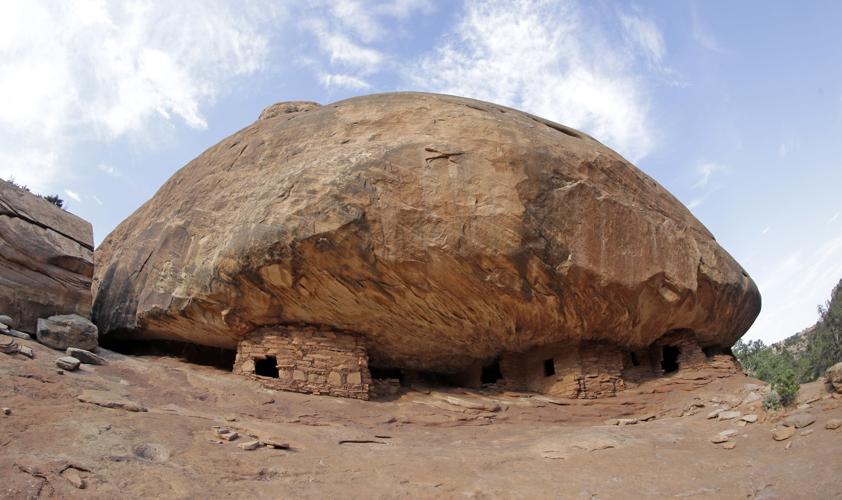

National monuments and mining. Udall and several Native American activists and academic experts said they expect Haaland to try to reverse Trump’s decision that shrunk Bears Ears National Monument in southern Utah by more than half. That was in part to accommodate potential uranium exploration on some of those lands, among other mining interests.

Arizona lawman and rancher John Slaughter is featured in a new exhibit at the Arizona History Museum in Tucson. Slaughter's famous San Bernardino Ranch hugs the U.S.-Mexican border in Cochise County. Video by Ron Medvescek / Arizona Daily Star

“We didn’t have anyone within the government who can see how these areas affect the tribes that have traditional ties to those areas. Now we will. Now we do,” said April Ignacio, an O’Odham who chairs the Arizona Democratic Party’s Native American caucus.

“I think it would be our hope that she would at least continue to advocate on behalf of tribes who are trying to protect those areas from toxicity, whether it’s mining, the fracking or the loss of water,” Ignacio said.

She specifically mentioned the Rosemont Mine, although the Interior Department has no permitting authority over it. Much of it would lie on land in the Santa Rita Mountains southeast of Tucson that’s managed by the U.S. Agriculture Department’s Forest Service.

But Interior’s U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service gave Rosemont a crucial legal clearance under the Endangered Species Act. Its Bureau of Land Management raised big concerns about Rosemont impacts during the Obama administration.

Lawsuits filed by the Tohono O’odham and two other tribes and environmentalists now have that mine stopped in federal court, pending appeal of a Tucson-based federal judge’s ruling in 2019.

Tribal activists also mentioned the ongoing battle over proposed copper mining at Oak Flat on federal land near Superior that the San Carlos Apache tribe considers sacred. That mine, too, is a Forest Service issue, although activists such as Amy Juan, community programs coordinator for the Tucson-based International Indian Treaty Council, say they hope Haaland can have an influence there, too.

Reached for comment, the leading mining trade group, the National Mining Association, was noncommittal about Haaland’s nomination.

“We’re a nonpartisan organization that works with all administrations and all appointees. We don’t want to prejudge those interactions and we look forward to educating the new administration about our priorities for the future and how we feel mining can contribute to (economic) recovery,” said Conor Bernstein, the association’s spokesman.

Vigneto and the San Pedro River. Grijalva said he hopes Haaland could provide a “whole restart and a true environmental analysis” for the 28,000-home Villages at Vigneto development proposed near the San Pedro in Benson.

Interior’s Fish and Wildlife Service had ordered a detailed environmental analysis of that project in 2016. Then it backed off a year later, under what former Fish and Wildlife official Steve Spangle said was political pressure from higher-ups. Trump’s Interior Secretary David Bernhardt has acknowledged taking part in Interior’s move to reverse Spangle’s stance but said it was strictly a legal issue. That project has been federally approved but is also being challenged in federal court.

Grazing. Interior’s BLM faces two big Southern Arizona grazing issues as Haaland prepares to take the helm as secretary.

First, a lawsuit is pending against the bureau’s continued approval of cattle grazing on 12.5% of the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area, lying east of Sierra Vista.

The bureau’s 2019 plan also allows introduction of what the bureau calls “targeted” grazing into the rest of the conservation area, which has been officially closed to cattle since the conservation area’s creation in 1988, says the lawsuit.

In the suit, four environmental groups say the plan violates the National Environmental Policy Act, the Federal Land Policy and Management Act and the 1988 Arizona-Idaho Conservation Act, which created the conservation area that covers more than 40 miles of the river.

Separately, the bureau has approved a plan to open 255,000 acres of the 496,000-acre Sonoran Desert National Monument north of Tucson to cattle grazing.

Environmentalists have raised concerns that the introduction of cattle there could disturb fragile soil and plant life, including saguaros, and threaten the desert tortoise populations that are native to that area.

That decision, too, may draw a court challenge, particularly since it was made by former BLM Director William Perry Pendley, and a judge has ruled that all of Pendley’s decisions in another state — Montana — are no longer valid because the Senate never confirmed his appointment.

Roaring fires and rising waters: 5 definitive takes on climate change

Get past the political bluster surrounding climate claims and explore the data for yourself here. View changes and consequences of our weather and climate.

Since 1980 high-cost disasters such as hurricanes and flooding have totaled more than $1.75 trillion in damage. They're becoming more frequent, and more damaging.

Eight of the 20 most-at-risk cities are located in one state, and a large majority are located in the South.

The residents of this small riverside town have become accustomed to watching floods swamp their streets, transform their homes into islands and ruin their floors and furniture.