On Aug. 4, 2020, after more than 14 years of struggling with addiction, Naomi Vega's eldest son passed away from a drug overdose.

Jesus Gilberto Gutierrez's untimely death is part of another pandemic that runs parallel to COVID-19: a pandemic that during the last 10 years has claimed the lives of more than 500,000 people in the United States, according to figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The origin of this pandemic, of course, is not a virus; it is the sustained use of various types of opioids and substances, both legal and illegal. In Pima County alone, between January 2021 and June 2021, drug overdose has claimed 245 lives.

“People think that when we talk about overdose we only refer to drugs such as amphetamines, opium, heroin or cocaine,” says Vega, “but in reality many people lose their lives to alcohol and many other drugs, even legal ones. It is more complex than you imagine.”

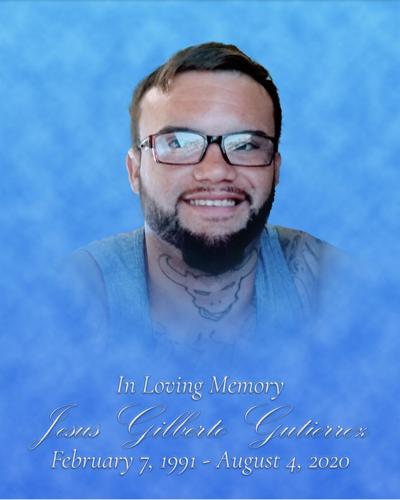

Jesús Gilberto Gutiérrez

For many years, Vega saw her son's struggle with addiction and self-destruction. After his death, she, her family and close friends created the Enlightening Hope Project, a nonprofit organization dedicated to supporting people with addictions and their families.

On Tuesday, Aug. 31, the foundation is organizing a special event dedicated to the memory of victims and to provide education on the subject within the framework of the International Overdose Awareness Day. The event will be held from 5 to 8 p.m. at the Gene C. Reid Park in Tucson, 900 S. Randolph Way.

Jesús Gilberto Gutiérrez

The difficult path

of seeking help

From her own experience, Vega knows how complex it is to take a step forward in the search for solutions to addiction problems. Although the Tucson Police Department has a program that provides aid instead of jail time to drug users, it is easy to overlook the necessary steps to take when a person or their family members seek detox or rehabilitation services.

As they begin to face this challenge, Vega says, "many of the families do not know what words to use to request these services, where to go or how to handle this with their insurance."

Vega, who has worked in mental health organizations and knows the inner workings of health insurance in the state of Arizona, says that the first step is for the person coping with addiction to feel ready to embark on the path towards rehabilitation. Family members cannot help those who are not determined to break free from addiction, she says.

When they have taken the first step, Vega explains, family members can seek support from the foundation.

“Mothers, fathers, children or siblings call me and say: 'they’re ready — where can we take them?,'" Naomi says. "So I ask them what insurance they have and I make a list of all the places here in Tucson, or in Maricopa County or Cochise County, or if they live in another state, I look it up."

'We have to leave

behind shame'

According to figures from the Arizona Department of Health Services, more than two people die every day in the state from opioid overdoses. In the last four years, an estimated 10,200 people died from overdose in Arizona. However, although the figures are clearly alarming, they do not encompass the true number, since uninvestigated cases remain uncounted.

Despite the numbers, this subject, as Vega explains, remains a taboo for families.

“My son, unfortunately, died on the news, everyone saw it. And there were many comments: that he was a ‘waste’ to society, that as a mother I should not have cried or been sad," says Vega. "That hurt me a lot, because my son was a good man, a good son. Yes, he was an addict, he lived in the washes or begged for money, but he was my son. I always saw him as my little boy, my first son.”

Gutierrez's death was made public because it happened while he was in police custody and the Tucson Police Department is required to release information when someone dies at a scene where they are present.

As part of the pedagogical component of her project, Vega aims to educate the community on the importance of talking about what addiction means and the complexities of dealing with it.

"You can be the best mother in the world, have a house in a castle on top of a hill, but if addiction finds its way to someone you love, that will affect the whole family," she says.

The name of the foundation, Enlightening Hope Project, stems from the need to address the taboo surrounding addiction through education to change people’s perspective, to bring light to the darkness.

The compassionate look Vega proposes implores us to go beyond our perceptions of the "dirty" person on the streets in their own struggle with drugs, and to see him or her as someone's son, nephew, grandson, brother or sister.

"Wherever that person is, I can swear that his mother, his aunt, his grandmother, his brothers, are crying for them, and praying," Vega says.

'There is hope'

As Vega continues to go through her own grieving process and cope with the loss of her 29-year-old son, she has decided, for herself and in his memory, to transform her inner light into a desire to help others. She believes that “recovering from an addiction is not impossible, and not all cases end fatally. That is why our project exists, to say: there is hope.”

When Vega receives calls from people or family seeking support, she provides for them a space without prejudice or shame, to vent their feelings, thoughts and frustrations.

Her first advice for the relatives of the affected person is: “Talk to them. Ask what is wrong with them. Tell them: 'look: I love you very much, I'm here for you when you're ready.'”

Vega suggests that family members seek help for themselves because, as she says, "the only person you can really help is yourself." She refers to seeking psychological support and preparing oneself to know what to do when a family member expresses the willingness to seek a way out.

Along with the enormous effort that Vega makes every day to sustain the foundation, she dreams of the possibility of creating courses for community colleges that cover topics ranging from prevention and knowledge to health service scenarios on the subject of overdoses.

“Society cannot function if you don't help others. If I want to educate myself in the community, I must also aim to educate others. If I need help from my community, I must also help others,” she says.

Due to Covid-19, Splash and Cody, two therapy dogs, have not been able to visit with patients, so they made a special trip to see staff on August 27, 2021. They received many pets and belly rubs for two hours. Splash is retiring since he lost his eyesight. Cody will visit TMC once a week and hopes to see patients in the pediatric unit soon.