The Flying Tigers were legendary for their bravery and their daring during World War II. In his book “The Flying Tigers,” Tucson native Samuel Kleiner set out to tell the personal stories of those who flew bombers for China against Japan. An excerpt from his just-published book:

The freezing temperatures in New York City on December 7, 1941, didn’t stop more than 55 thousand football fans from packing the stands at the Polo Grounds in upper Manhattan. This was the highly anticipated crosstown-rivalry game between the New York Giants and the Brooklyn Dodgers. After the underdog Dodgers took a 7-0 lead, they kicked the ball down the field, and listeners at home heard the announcer on WOR radio call the play. “It’s a long one, down to around the three-yard line,” he said, and the Giants’ Ward Cuff made the catch and started to run it down the field. Over the cheers of the crowd, the announcer continued: “Cuff’s still going, he’s up to the 25 and now he’s hit, and hit hard at about the 27-yard line. Bruiser Kinard made the tack—”

Suddenly, the reporting of the game was cut off as another voice broke in: “We interrupt this broadcast to bring you this important bulletin from the United Press. Flash Washington. The White House announces Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Stay tuned to WOR for further developments, which will be broadcast immediately as received.”

Inside the stadium, the game went on without any kind of announcement. The crowd watched as the Brooklyn Dodgers clinched an upset 21–7 victory. The sun was setting as the fans headed for the exits. Then the public-address system came on: “All navy men in the audience are ordered to report to their posts immediately. All army men are to report to their posts tomorrow morning. This is important.”

“There was a sudden, startled buzz in the crowd,” the sportswriter for the Brooklyn Eagle reported. “What had happened? No one knew, not until he got close to the nearest radio or within hearing range of newsboys yelling in the streets.”

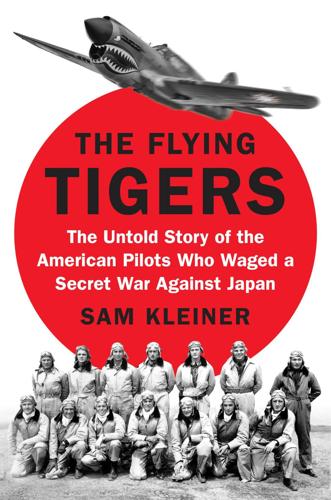

An American Volunteer Group P-40 taking flight, 1941.

The Navy Department’s censors delayed releasing photographs of the destruction in Hawaii, but on December 29 Time magazine featured them in its coverage of the “Havoc in Honolulu.” One image showed large clouds of black smoke rising from the wreckage of the U.S.S. Arizona, and another, a P-40 fighter plane that had been wrecked on the field and “never fought.” A hangar at the army’s Hickam Field had also been destroyed. This was the carnage from “Japan’s sneak attack.” Time carried a dire headline in that December 29 issue: “INVASION OF THE U.S.?” It reported that anti-aircraft guns were deployed to New York City to defend “power plants, aircraft factories, docks, and shipyards,” against the threat of a Luftwaffe attack. The fear was more pronounced in the West: “At forest-fire lookout towers, in little tarpaper-covered shacks scattered on the hills along the coast, spotters watched the grey skies, 24 hours a day, in three-hour shifts.” San Francisco was blacked out, and reporter Ernie Pyle said that its darkened streets looked like “the dusty remnants of a city dead and uninhabited for a hundred years.”

But that edition of Time included another story, one that would capture the imaginations and raise the hopes of Americans in the dark days after Pearl Harbor. In China, a unit of U.S. volunteers was battling the Imperial Japanese air force, whose planes had been bombing Chinese cities and killing thousands of civilians for the past four years. They were known as the Flying Tigers, and Time reported their exploits in stirring fashion:

“Last week ten Japanese bombers came winging their carefree way into (China), heading directly for Kunming … the Flying Tigers swooped, let the Japanese have it. Of the ten bombers, said (Chinese) reports, four plummeted to earth in flames. The rest turned tail and fled. Tiger casualties: none.”

Mechanics and airmen gather around the engine of a P-40, also known as a Tomahawk, during training in Toungoo, Burma.

Members of the Tigers would soon become familiar figures: their leader, Colonel Claire L. Chennault, and pilots like David “Tex” Hill and “Scarsdale Jack” Newkirk. Years before American soldiers stormed the beaches of Normandy or raised the flag on Iwo Jima, it was Chennault’s Flying Tigers who rallied the country with victories when the Axis at times appeared unstoppable.

“A hundred American volunteers had taken the measure of the enemy,” Clare Boothe wrote in Life. “Who, in the face of that measure, dared doubt that America could—if it would—defeat Japan?”

The Flying Tigers’ shark-nosed P-40s — also known as Tomahawks — would go down in history as one of the iconic images from World War II. Hollywood executives knew a heroic story when they saw one, and in 1942 Republic Pictures rushed out Flying Tigers, starring John Wayne as the swashbuckling commander of the unit. Hollywood produced its own version of their adventures, but the truth was that the pilots were “doing deeds that a movie director would reject, in a script, as too fantastic,” as Time described them in April 1942.

Despite the hyperbole, the Flying Tigers were indeed undertaking an important mission: They helped keep China in the war. If China fell, Japan would be able to focus its forces against an unprepared and under-armed United States.

It would take five decades for the Pentagon to acknowledge the truth about the Flying Tigers — namely, that the mission was a covert operation authorized at the highest levels of the Roosevelt White House, in violation of America’s neutrality, and out of view of an isolationist Congress, months before Pearl Harbor. Its pilots and crew resigned from the U.S. military, bade their loved ones farewell, and crossed the Pacific on ocean liners, carrying passports listing false professions to disguise the truth about their mission. Over 100 pilots arrived at a makeshift camp in the jungles of Burma, to discover planes they didn’t know how to fly. Determined and desperate, they drilled in new techniques to fight the Japanese air force’s more agile planes, and were just about to enter into battle when the Japanese struck Pearl Harbor. When President Roosevelt declared war, they were the only Americans for thousands of miles, outnumbered and with no reinforcements coming. Yet between December 20, 1941, and July 4, 1942, they shot down scores of Japanese planes in Burma and Southern China.

For 75 years, the most detailed account of the Flying Tigers lay buried in pilots’ diaries and letters that were hidden away in closets and at the backs of drawers after the war and in combat reports that lay moldering in the basement of an unremarkable brick building in Georgetown. Their achievements are even more remarkable and stirring than the myth created by Hollywood.