My class had just come in to the cafeteria when the teacher gathered us together. She made an announcement that has stayed with me for more than half a century:

A classmate’s father had been killed in Vietnam.

We were fourth-graders at midtown Duffy Elementary, war and death the furthest things from our minds.

And it wasn’t just us: Until that day, such news was unheard of in all of Tucson.

It was 1965 — before the war came into our living rooms nightly on the network news — and my fellow fourth-grader’s dad was the first Tucsonan confirmed to have died in Vietnam, a place most of us had never heard of.

“Be extra nice to Billy Kelley,” my teacher said that day.

For so many years, I recalled everything about the moment except Billy’s name and always wondered how his life turned out. I pictured the desperation I’d seen on his face and hoped anger hadn’t consumed him.

With another Memorial Day approaching, I decided last week to solve this mystery of my childhood and to explore this shared experience of my generation.

Ours was a generation that came of age with that war, where fathers and older brothers disappeared across the globe and, eventually — when we were in high school and it was still raging — many of the boys worried they themselves would be drafted after graduating.

• • •

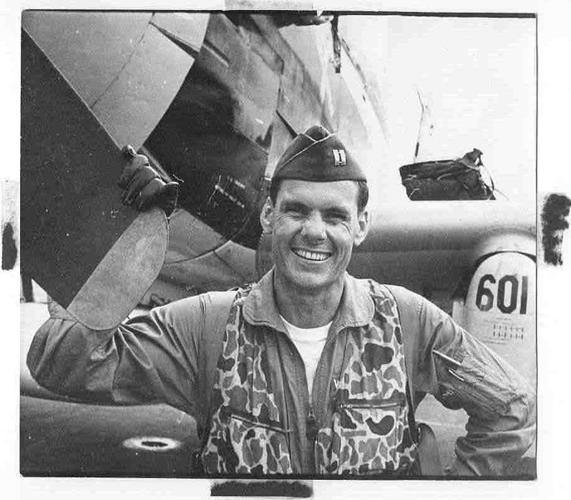

Air Force Capt. James Atlee Wheeler was the first Tucsonan to go missing in the conflict, when his A-1E Skyraider blew up over South Vietnam on April 18, 1965.

It was Easter Sunday, and his son Jimmy Wheeler was, like me, a 9-year-old Tucson fourth-grader, but at Sam Hughes Elementary.

He and his younger brothers, Ray and Stewart, were with their mother in Phoenix visiting their uncle for a picnic. “Mom was out of sorts all day, like she just knew something was wrong,” James A. Wheeler Jr. remembers.

The next day, his mother, Demeris, was driving Jimmy home from a dentist’s appointment when they rounded a corner and saw an Air Force vehicle parked in front of their midtown Tucson home. “Mom just lost it,” he says. “She knew, of course. And those two were deeply in love.”

Wheeler had graduated from Tucson Senior High School on May 30, 1950 — 67 years ago this week — with classmates who would later become Arizona Supreme Court Chief Justice Stanley Feldman, famous folk singer Travis Edmonson and construction executive Harry Wilson Sundt.

He joined the Air Force in 1954 after attending the University of Arizona. As an experienced fighter-jet pilot and captain, he volunteered for duty in the fledgling Vietnam conflict, explaining to his oldest son, “Well, we’re trained, we’re going to go over there and take care of this, so none of our young men have to go.”

He had flown 40 combat missions in two months’ time, while also running training missions for South Vietnamese pilots, when he was lost during an attack on Viet Cong guerrillas. He was 32.

James Jr., like most of us our age, hadn’t thought about Vietnam at all. “I knew my Dad was in war, but it never crossed my mind that something could happen to him. It really didn’t,” he says today.

Despite the family’s tragedy, “All my best memories of growing up are in Tucson,” says James Jr., who is now 61 and a commercial construction superintendent in the Dallas-Forth Worth area.

Not the least of the reasons for his affectionate memories was the treehouse with real windows his dad had built for his boys in their backyard. “It was top of the line, I’ll tell you.”

Another reason: “Unlike a lot of the stories that you hear about our veterans being killed, we were treated with the utmost respect. We had a deep sense of pride in everything that he’d done. You grieve, of course, but the honor shown to him helps you get through it.”

So much so that, “Growing up, I wanted to be a fighter pilot,” he says.

By the time he graduated from high school in 1973, however, in his mom’s home state of Texas, “There were (Vietnam) protesters and nonsense every day. I wondered, ‘Why would I lay my life on the line for people who feel this way?’ That’s a decision I still regret; I get pangs when planes fly overhead.”

His mother had a different worry — that it wouldn’t even be left up to her eldest, teenage son whether to serve in the war.

He says his draft number put him at real risk of being drafted.

That’s how it was, too, for some of the guys I went to school with at Sahuarita High from 1969 to 1973, those who were a few years older than me and, mostly for financial reasons, not college-bound but headed to good-paying jobs at the mines. The inescapable draft weighed heavily on them and probably contributed to the recklessness of some of our parties in the boonies.

James Jr. recalls his mother’s cries: “When my draft lottery number was 40, I remember she said, ‘You’re going to Canada. I’m not going to lose another one in Vietnam.’” He said no way, they were a patriotic family. Fortunately, the draft ended the year he graduated.

Although it was declared right away in 1965 that Capt. Wheeler couldn’t have survived his plane’s explosion, his remains wouldn’t be found until 1998, when searchers recovered bone fragments from the crash site. They wouldn’t be confirmed as his until six weeks after 9/11. His widow and sons buried his bones at South Lawn cemetery in Tucson, where Demeris, now in her 80s, has a plot where she will one day come to rest next to him.

• • •

Until the 2001 confirmation that the long-missing James Wheeler had indeed been the first Tucsonan to die in Vietnam, that sad distinction belonged instead to Victor Bruce Kelley, his own son remembers vividly.

Bill Kelley was a fourth-grader — with me, it turns out — at Duffy in late April of 1965.

“I remember that day like it was yesterday,” he begins. He was out sick, or pretending to be, and at his grandmother’s house when she took a call in her bedroom. “I could hear her saying, ‘Oh my God, I can’t believe it, Oh my God!’

“And then, she did the weirdest thing, she came out and said, ‘I have to go see your mom.’ I was feisty, and wanted to know why and didn’t take ‘no’ for an answer, so she told me. She said, ‘Your father was killed in Vietnam.’ I remember I just cried and pounded.”

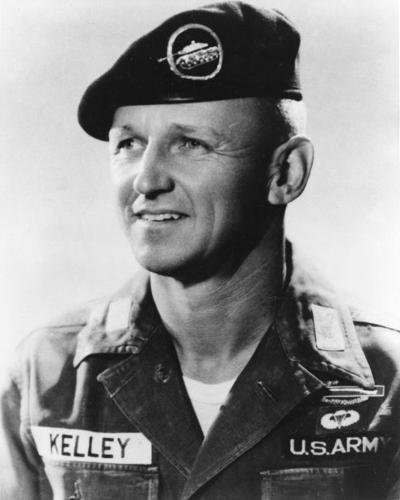

Bruce Kelley, as his father was known, had earned his Army commission through the ROTC program at the UA, where his father, Victor, was a well-known professor. He served in the Korean War before coming back to Tucson as a civilian and earning a master’s degree at the UA.

In 1955, he moved with his wife, Patty, and their kids, Susan and Howard, to Oxnard, California, where he taught and coached. Bill and his younger brother, David, were born there. Bill’s childhood was fun, full of travels, including visiting Civil War battlegrounds with his dad.

But Kelley decided to re-enlist. He was a decorated captain when the Army sent him to Vietnam in the fall of 1964. Patty and their four children moved back to his hometown of Tucson.

On April 28, 1965 — just 10 days after Wheeler went missing in action — Kelley was on a rescue mission.

He left his helicopter in search of a wounded American colleague, found him and hoisted him over his shoulder. A sniper’s bullet struck Kelley in the head, killing him instantly.

He was 36 and had already completed his tour and been reassigned, scheduled to transfer to Leavenworth, Kansas, but had volunteered for the fatal rescue attempt.

Bill thinks often of how his life would have been dramatically different if not for two critical junctures. The first was when his father re-enlisted in 1958. “If we’d stayed in Oxnard, I would have been a California surf kid in the ’60s,” he muses, adding, “I do fantasize about that.” And the second, of course, was that April day in ’65.

“It was very sad for my family. My father was a strict disciplinarian. When that discipline and structure was gone in our family, my mom couldn’t compensate,” Bill says, describing the following years as “loose” for the four kids, meaning, “We’d go wherever we wanted whenever we wanted.” He describes himself and his friends back then as “knuckleheads” who went pretty wild, but adds, “I look back on that fondly,” as it was part of becoming independent, growing up and discovering.

“My mother was great. Mom was always positive, despite our misdoings,” Bill adds. “Another thing that really helped me growing up was that I had teachers who were engaging and interactive, and mentored me” — including his fifth-grade teacher at Duffy, Estelle McDoniel, with whom he reconnected a few years ago.

McDoniel recalls that when Billy entered her class the fall after his father’s death, she was new to Duffy and didn’t know what he had been through. Teachers would send a couple of paragraphs about each child to their next teacher, but her philosophy was to “wait and see what a child is like in my classroom.”

“I didn’t see the trauma that I’m sure he and his family had gone through.” He was well-adjusted, she says, and part of a delightful, memorable class. “But it had to be a tough go. I can’t imagine what he had to go through,” McDoniel says.

In the summer just after Wheeler’s and Kelley’s deaths, President Lyndon Johnson’s buildup of the war effort began in earnest, and in the following years, there were “lots of bodies coming home,” Bill notes. A total of 195 from Southern Arizona died there, among 600-some Arizonans and more than 58,000 Americans.

Bill says he remembers getting tear-gassed when he went to check out the anti-war riots at the UA because they were something “exciting going on.” He figures he was an eighth-grader or high school freshman then.

Unlike Jim Wheeler Jr., he didn’t worry about being drafted. That was a more pressing concern for his older sister’s class, which graduated in 1969.

“The war really was over when I graduated” from Rincon High in ’73, Bill says, remembering that it was like “the balloon popped and the pressure was off of us to go into the military. I didn’t even sign up for the draft. Nobody did then, and nobody cared.” Also, he says, he knew there were college deferments and “I was always going to go to college.”

Life turned out well: His mother went on to marry Don Smith “and they had a wonderful life.” She died a few years ago.

Bill Kelley, now 62, is married to Jamie, has two grown sons, Blake and Ross, and is the chief financial officer of Tucson development firm Diamond Ventures Inc. I phoned him out of the blue on Thursday and found him reluctant to be featured in this article. “I like to just get stuff done and be successful,” he says, emphasizing he doesn’t want the focus to be on him, but on his father’s service.

Although “horrified by the history of Vietnam,” Bill calls himself “a pro-military guy,” who serves on the DM50 group of community leaders who support Davis-Monthan Air Force Base and was a civilian squadron commander at the base. He’s part of a broader family known for community leadership and public service here.

Bill has been quoted as saying, memorably, that from the time he lost his father at the age of 10, he was aware that becoming bitter or resentful was a possibility.

He’s avoided that — he’s a genial, personable guy with a fun banter, who signs off on phone calls and emails with a sincere “All the best” — by focusing on this:

“The compelling thing for me is, that was my dad’s chosen profession,” he says, drawing a stark contrast to those who were drafted, reluctantly served and did not come home.

“Duty called, so he signed up for it.”