As we observe today’s centennial of the Nov. 11, 1918, armistice that ended World War I, we honor those who served by sharing the family stories of our readers, as passed down through the generations and told in their own words:

Tucsonan used Spanish to solve language barrier

My father, Ernest A. Sayre, was born on Meyer Street in the Old Pueblo on Sept. 5, 1895. In 1917, he enlisted in the Army and left his home at 521 S. Sixth Ave. for Fort Riley, Kansas. He often spoke of the train trip to Fort Riley, his first journey outside of Tucson.

Ernest A. Sayre served in France and Germany. He was exposed to gas used by the Germans and lost his sense of smell.

He was impressed by the hospitality shown in the town of Liberal, Kansas. The ladies of the town offered coffee and doughnuts through the windows of the train to the GIs on their way to war.

He served in the invasion through France and Germany. During the battles, he was exposed to the gas used by the Germans and lost his sense of smell.

He liked to tell the story of a language barrier in the field that caused a significant obstacle. Dad was in charge of an American platoon that had to work with a French contingent. The Americans spoke English and the Frenchmen only spoke French. Communications were at a standstill until Dad asked a Frenchman if he spoke Spanish. He did. The stalemate was then resolved, with each man translating to his men in their own language. Thus, communication in Spanish helped the two groups become effective.

Ernest Sayre was discharged as a master sergeant and was employed at Valley Bank until retirement. After retirement, he and his wife, Anne, retraced his steps in France and Germany. With a guide, they followed the way of the troops, seeing the barn were they slept in France. They passed the site of a bridge they blew up, still in ruin. This trip had always been his dream.

He died in Tucson in 1982 at the age of 87. He was survived by his wife, Anne Jarrold Sayre, and three children, Shirley, Ernest Jr. (Jerry) and Merlene.

— Shirley Sayre Di Salvo

Native of Old Pueblo took part in Expeditionary Force

My great-uncle Gustavo Vasquez was a native Tucsonan, a cousin of Guadalupe Dalton Ronstadt, who was the second wife of pioneer Fredrick Ronstadt. Gus’ father was Adolfo Vasquez, a blacksmith in a carriage shop he operated with his partner, W.A. Dalton, in late 19th century Tucson. Gus was born in 1893.

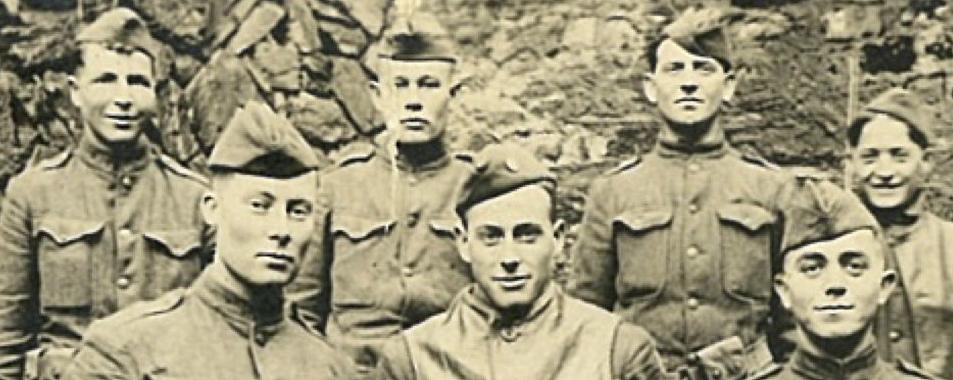

In March 1918, Gus Vasquez, second row, right, enlisted in the Army and was assigned to the 355th Infantry, 89th Division and became a sergeant in Company B, part of the American Expeditionary Force. The 89th Division arrived in France in early June of 1918, joining the First American Army in the Toul sector, where on Sept. 12 it took part in the Saint-Mihiel Offensive. In October, the unit took part in Bois de Bantheville offensive and in November the offensive continued across the Meuse River. Vasquez left the Army in early 1919.

In March of 1918, Gus enlisted in the Army and was assigned to the 355th Infantry, 89th Division, and became a sergeant in Company B. He became a part of the American Expeditionary Force.

The 89th Division arrived in France in early June of 1918. It then joined in the First American Army in the Toul sector, where on Sept. 12 it took part in the Battle of Saint-Mihiel. In October, the unit took part in the Bois de Bantheville offensive and in November the offensive continued across the Meuse River. The 89th continued its advance until receiving notice that the armistice had been signed on Nov. 11, 1918. Gus left the Army in early 1919.

He went on to become the owner of the Tucson Livestock Exchange. He was also a former deputy sheriff from 1932-1936, a founder of the Club Latino and a member of the Morgan-McDermott American Legion Post 7. He died in 1957.

— Mike Morales, Tucson

Training manual trapped shrapnel, saved his life

My family has a shadow box containing my grandfather Joseph P. Osterman’s picture, his Purple Heart, a summary of two battles he was involved in, and, most importantly, the piece of shrapnel that is still in his military training manual.

My father, Frank Osterman, told me the story:

While stringing wire in the Meuse-Argonne Forest, my grandfather and a fellow soldier decided to take a rest. My grandfather had struggled to get the radio pack (I’m sure it was rather large 100 years ago) to stand up. He woke up 30 minutes later to see his fellow soldier had been killed with the shrapnel that was also meant for him. However, the training manual saved his life.

Joseph P. Osterman was awarded the Purple Heart after getting wounded in action at the Oise-Aisne area of the campaign.

My Grandpa Joe was awarded the Purple Heart after getting wounded in action at the Oise-Aisne area of the campaign. I’ve often wondered over the years, who or where I would be if my grandfather hadn’t made it.

— Dan Osterman, Tucson

Served proudly with Capt. Harry S. Truman

My dad, Floyd Lowe, was a very proud soldier who enlisted during WWI at the age of 22 in Pierce City, Missouri, where he grew up and at that time was attending college. He served in France with Capt. Harry S. Truman and returned to the United States on May 1, 1919. He then married my mother and they settled in Southern California. He had a chance to run into President Truman after he left the White House while Dad, after he retired, was visiting Independence, Missouri. Harry was taking one of his regular daily walks and dad yelled out “Captain Harry” and he responded “someone here knows me.” They chatted for a while and it was a real highlight for my dad.

Floyd Lowe served with Capt. Harry S. Truman, later to be president, and ran into him after the war in Independence, Missouri.

While I was growing up in the ’30s and ’40s, we had a wash house in the backyard where dad hung his uniform, and he gave it a salute every day. In those years he still had a lot of soldier in him, and when he called me to stand at attention, believe me, I responded. I did learn a great deal from him, especially regarding respect for authority. I remember when I asked him if I could take his medals off his uniform and he gave me permission to do so; I was probably 11 or 12 years old at the time. This was during WWII and dad knew I was collecting anything relating to the military.

So many gave the ultimate sacrifice during our many wars and conflicts. Those are the ones we honor with the flag of the United States of America.

— John Lowe, Oro Valley

Learned to march with a wooden gun replica

My father, Max Ross, enlisted in the Army in September of 1917. As a First Colorado Cavalry recruit, he was issued a saddle but never got a horse to put the saddle on. Guns were also slow in arriving, so he learned to march with a wooden replica.

Max Ross, as a First Colorado Cavalry recruit, was issued a saddle but never got a horse to put it on.

After his unit was transferred to the infantry, he volunteered to be sent to the battlefront in France. He participated in three major battles there. When the armistice ended the war, his division, the 32nd, was awarded the honor of being first to enter Germany.

As a child growing up far from an ocean, I was intrigued by my father’s description of the ship that brought him back to our country. His recall of those battles always impressed me.

As the anniversaries of those times came around, he would tell his family exactly where he was on a particular day in 1918. He was my hero!

— Lois Blacker

French Marshal Ferdinand Foch and Gen. John Pershing, front row, center. Col. John M. Morgan, West Point Class of 1893, is in the back row.

West Point grad earned Distinguished Service Medal

John M. Morgan, West Point class of 1893, was originally commissioned in the U.S. Cavalry. However, on June 5, 1917, he was commissioned colonel of infantry and assigned to the command of the 309th Infantry. He arrived in France with his regiment on June 9, 1918, and served in the Ypres and Arras sectors with the British, but then transferred to the American sector in the Saint-Mihiel and Argonne operations. Col. Morgan returned with his regiment to the U.S. on June 1, 1919. His regiment was part of the famed 78th (lightning bolt insignia) Division. He was awarded a Distinguished Service Medal for his leadership and continued his career in the military until his retirement.

He is my grandfather on my mother’s side.

— Margaret G. Kurtin, Vail

Tanks, like this German model, were developed to break the stalemate, but were largely unreliable.

Left Arizona mines to fight in “the Great War”

My father, Pvt. Josephi Lo Turco of the English Battalion fought in the “War to End All Wars.”

He was a young Sicilian immigrant who came to America at 17 years young. The gold mining fever was still a lure for a young man like him. He made the trek from New York to Southern Arizona. Hard-rock mines were always looking for laborers, so he was never idle.

Entries in his journal have many of his Army experiences. He enlisted on Sept. 20, 1917, shipped out of Long Island, New York, on the RMS Carpathia to Liverpool, England. There are a lot of details in this little journal. A lot of it is stories of boredom, constant rain, terrible shelling, marching from town to town and the awful KP duty. What soldier has ever forgotten that?

Private Josephi Lo Turco, right, of the English Battalion enlisted on Sept 20th 1917, shipped out of Long Island, NY on the RMS Carpathia to Liverpool, England.

One of the more famous locations in his journal was the march from Eumile to the Argonne Forest. There are entries about trench warfare, the mud and the enemy. He brought back two great trophies, a German Luger and a Mauser pistol. When asked how he acquired them, he simply said he picked them up on the battlefield. He never mentioned if he had to kill any of the Germans.

Another interesting and maybe more humane story of his is in relation to a photo of him standing with his rifle, a holstered .45 on his belt, a dead deer at his feet and the long barracks on one side. Toward the end of the war, the U.S. had a lot of POWs, and how to feed them became quite the task. My father, who liked to hunt and was an excellent marksman, was sent out to hunt for wild game for the stew pot. He hunted deer, wild boar, rabbits and birds. It was all good protein.

The journal states they took shelling until the armistice of Nov. 11, 1918, was signed. After that he came back to Arizona to work in the mines, mostly in Hayden, Winkelman, Globe and Miami. He did some bootlegging during Prohibition. My father died in 1970 at the age of 79. I still have his dog tags.

— Ben La Turco, Tucson

Only son made the ultimate sacrifice at age 20

My great-uncle, Manford Wesley Clarke, served with the 46th Battalion, Canadian Infantry, during WWI. Manny survived the Battle of Amiens and marched out at the beginning of the Hundred Days Offensive, which culminated in the end of WWI. While carrying out his duties as a tump liner on Aug. 19, 1918, he was gassed. Immediate attention was given him at the Regimental Air Post, and he was later evacuated to No. 48 Casualty Clearing Station, where he died a few days later. He died during the night of 25-26 August 1918. He was only 20 years old and his parents’ only son. He is buried in Villers-Bretonneux Military Cemetery, Somme, France.

Members of my family have served in every war the United States has ever had, from the French and Indian War until today. Only one did not survive, Pvt. Manford Wesley Clarke.

— Bette Bunker Richards, Marana

“We broke the church bell ringing all day”

When the war started, my grandfather, Albert J. Magee, was enlisted in the Naval Reserve, but got a discharge from the Navy and enlisted in the 1st Battalion Company B Engineers on May 31, 1917.

Albert J. Magee, grandfather of reader Catherine McCord.

After Albert went to grenade school, gas school and bayonet school, he left for France on June 19, 1918. From France, he was sent to Switzerland, and from there to Hagenback, a German town on the Rhine. One of his many details was to collect and cut wood and cut iron beams for machine gun emplacements and to make camouflage sheets for same. After readying all this during the day, he was sent with the trucks to deliver this equipment to the trenches every night. After these deliveries, my grandfather would head back on foot, taking shortcuts across the fields. One night a GI from the infantry guard held him up with a .45 gat. He thought my grandfather was a German.

In September of 1918, my grandfather was sent to Avocourt, France, to repair roads. Another interesting incident he noted was in October of 1918, when he was ordered to take two platoons to deliver and install wire in the trenches near Molleville Farm. Upon arrival, he stated they were unable to reach the location due to “too much shelling and dead GIs on the field that we had to cross.”

On Nov. 11, 1918, my grandfather was waiting alongside the road, with more equipment, waiting on trucks to take them to Metz, France, when the men learned the war was over. He states, “We broke the church bell ringing all day.”

— Catherine McCord

3 brothers took part in huge offensive

As fate would have it, I am the son of a WWI combat veteran. At 70 years old, I am a certified geezer, but in the context of the historical continuum I am a bit of an oddity. My father, Leo Charles Spies, was 52 when I was born and would live to be 83.

Besides my father, two of his brothers, Ed and Jack, served. Jack, with the 110th Engineers, was wounded by shrapnel in the forearm and would thereafter have the two middle fingers of his right hand remain permanently fully extended and stiff. My other uncle, Ed, was a hospital corpsman. I must have channeled him when I became an OR tech in a M.A.S.H. hospital in Vietnam 50 years later. Uncle Harry, an uncle by marriage, served with the field artillery. All served in the 35th Division, comprised of recruits from National Guard units formed from Missouri and Kansas. They all took part in the huge Meuse-Argonne Offensive, which would ultimately decide the fate of the war. The division’s most notable member was probably artillery Capt. Harry S. Truman. It also included Dwight Davis, of Davis Cup tennis fame.

A few comments that were uttered and/or remembered from and about these people:

Dad (Leo, an infantryman with the 138th Infantry) received burns from shaving with water from a shell crater containing dissolved mustard gas.

Leo Charles Spies was struck by shrapnel, giving him a permanently deformed hand.

(While looking out the porch screen door into the darkness on a warm evening): “Forty years ago today we went over the top.” I don’t remember him saying much after that.

“We were going forward at night and men on both sides of me were killed by machine gun fire.”

Uncle Harry (artilleryman):

“I asked a minister once, ‘During the war we were ordered to fire on a group we knew were a German burial party. What did that make us in the eyes of God?’”

Uncle Ed (the hospital corpsman):

“A German soldier gave me this watch for taking care of him in our hospital.” (Ed kept the watch all his life.)

As a teenager, I visited the Truman Library in Independence, Missouri. My father wanted to donate his Army-issue mess pan to the library, considering the president’s connection with the 35th Division. On the lid my father had inscribed with a pen knife all the towns his unit had passed through.

While we viewed the exhibits at the library, a young page walked by. My father stopped him and asked, ”Do you think I could speak to the former president? I have something to donate to the library.” This was met with a predictable teenage eye roll and self-conscious embarrassment on my part. The page thankfully quickly departed and we continued our tour of the library. Probably 10 minutes later, the same page came up behind us and said, ”The president will see you now.” At which time we were led to his personal office at the library.

He was standing in front of his desk in the room. He looked “old” and predictably tired, but immediately demonstrated that he was still sharp. When my father presented him with the mess pan, his first remark was, “Where’s the cup?” The office was spacious and contained a grand piano. My father asked him, “Is that the piano you used to play ‘The Missouri Waltz’ on?” I don’t remember the president’s reply, but he did not seem at all in a hurry to get rid of us. I like to think it was just a couple of old vets exchanging a few recollections.

— C.E. ”Charley” Spies, Sycamore Canyon / Corona / Vail

“Letters from a Lonesome Aviator”

“American Official Communiqué No. 197, Nov. 11, 1918: In accordance with the terms of the Armistice, hostilities on fronts of the American Armies were suspended at 11 o’clock this morning.”

My father’s reaction: “It would seem that the above should at least have had an exclamation mark.”

Tucsonan W.C. “Bill” King served as a bombardier with a French unit and won the Croix de Guerre.

I read that riposte in his World War I memoir “Letters from a Lonesome Aviator,” which I discovered long after he’d died. Unzipping his portfolio, I found letters from 2nd Lt. and Croix-de-Guerre recipient Bill King writing his bride from “somewhere in France.”

Map-laden detective work with the letters, haunting French newspaper morgues and buttonholing French mayors led me to all his postings in my VW camper van, thus deepening my identity as my father’s daughter.

Called up in October 1917, the young man eager to serve his country rolled out from his Tucson home on the Sunset Limited to join a French escadrille as a bombardier.

“I have been enjoying some great flying. You put on a woolen helmet, then a cork one over that (this is supposed to confine your injuries to a headache in case you land on your head), then slip on a pair of goggles. ... They are helpful in convincing yourself that you bear some resemblance to a flyer.”

He flew in the back of Breguet bombers for seven weeks, far exceeding a bombardier’s two-week life expectancy.

On one sortie, “We had been in the air for three hours and were thoroughly exhausted. Such flying is very tiring for at any moment a bunch of Fokkers may dart out of the clouds and surround you. Your nerves are taut every second, and when you finally relax the reaction leaves you rather limp.”

Flying at 5,000 meters, “The air is very thin and you find it impossible to get enough oxygen in through your nose and breathe through your mouth in great, long gasps. It began to get cold. ... I beat my hands together very enthusiastically, but there wasn’t much I could do about my feet, which seemed to be blocks of ice. Then they stopped hurting and I was worried for I was sure they were frozen.”

“Last night I fell to talking with a very distinguished-looking old French gentleman. Today was the first time he had ever seen an American soldier. Before leaving, he took me by the hand and said, very earnestly, that he wanted to thank me and my comrades for coming to the aid of France; that victory would now be assured.”

Recurrence of a childhood ear abscess grounded him, saving his life.

— W. Kimberly King, Tucson

Health deteriorated because of mustard gas

My father, Rex Cunningham, was born in Old Dallas, Arkansas, in 1889. He enlisted in the U.S. Army on Sept. 5, 1917. Dad was stationed in Camp Jackson in Columbia, South Carolina. He was a sergeant in Company E, 318th Machine Gun Battalion.

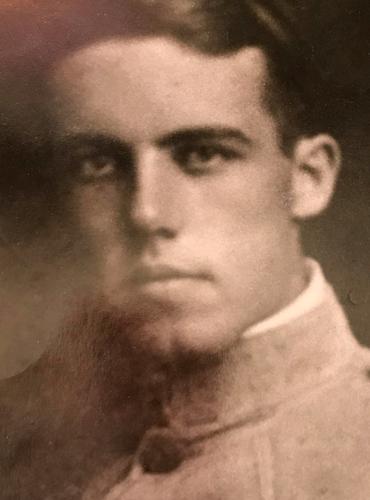

Rex Cunningham was a sergeant in Company E, 318th Machine Gun Battalion. He and his girlfriend, Mable E. Crumby, married in 1921.

After a short stay in Camp Jackson, he was deployed to France later in 1917. While in France, he sent letters and postcards to his girlfriend, Mable E. Crumby. After the war, he and Mable were married on June 18, 1921. They had a daughter, Frances Jean, in 1927. I came along in 1929.

My father was honorably discharged on July 3, 1919. During his tour of duty in Europe, he was exposed to mustard gas. In the years that followed, his health deteriorated due to the effects of the mustard gas. He entered the VA Hospital in Fayetteville, Arkansas, on Feb. 18, 1942. On May 21, 1942, he passed away at the young age of 53. I was 13 at the time.

— Hal Cunningham, Corona de Tucson

Hopes people will stop on 11/11 and remember

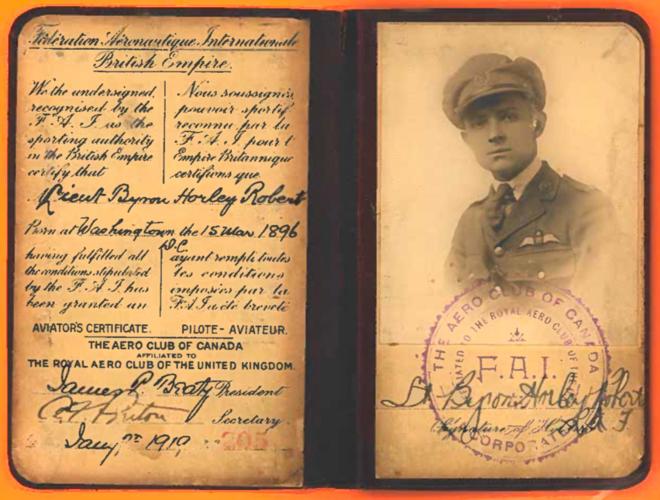

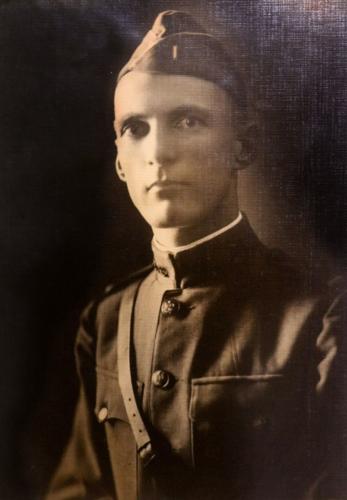

Both my grandfather, John Simpson Dawson, and my great-uncle, Byron Hans Robert, fought in WWI.

My grandfather, Jack as he was known, was in the U.S. Army Infantry, 110th Division, Company I. Although his official papers list him as a machinist, my father always told us that Jack was in fact a “runner” in France. This means that while in the trenches he would carry written orders from one unit to another by running through the trenches to make his delivery. Of course, this was before walkie-talkies and phones, so it was the only way to communicate outside of your immediate area. Jack was in several battles in France, but the most notorious was in Varennes. It was here that Jack took a watch from a German prisoner on Sept 26, 2018. Jack also received a medal for the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

John S. Dawson was a“runner,” carrying orders by running through the trenches.

Jack died when I was about 8 years old, so I never heard the stories directly from him and, now that my father has also died, there is no one left to tell the stories. The paperwork was handed down to me by my father.

In my early 30s, I visited some of the WWI battlefields in France. It was very emotional to think of Jack as a teenager seeing the horrible carnage there. He was very lucky to come home alive.

My great-uncle Byron was a real character. He reminded me of Fred Astaire because of his slight build and, coincidentally, flew with Vernon Castle’s 84th Canadian Training Squadron, Royal Flying Corps. Astaire would later star in a movie about Vernon Castle.

Byron H. Robert flew with the Vernon Castle’s 84th Canadian Training Squadron, Royal Flying Corps. Byron was a US citizen but joined the RAF in Canada. Byron was trained as a flyer in the Royal Air Force.

I really regret not interviewing my father more when he was alive about his father and his uncle. These pieces of personal history are going to be lost to us, and that is very sad. I hope that people will stop on 11/11 and remember the tremendous sacrifice of these young men.

— Gail Cusack

Finding Granddad through handwritten documents

Soon after my 80-year-old mother died in 2013, I found among her belongings her father’s cooking notes from his time in the British Army in WWI.

It was gray school paper and had his handwritten illustrations and recipes on how to cook for 100 men.

Until then, what I knew about my Granddad’s early life was this: He served in WWI and was a 40-year-old bachelor when he married Nanny, who had five kids, and the two of them went on to have four more, including my mother.

I know a bit about my mom’s experience as a child living an hour north of London during WWII, but I can’t remember ever asking Granddad about his war.

I told the Star’s editor for this WWI project that I would be writing about my English granddad and his fascinating cookbook.

As I write this, I still cannot find where I put it.

Efforts to reach my mother’s last living sister in England didn’t work. So I did what most of us would do: I Googled his name. Here’s what I found on an English website:

George Fines Mountain, from Yorkshire, served in the British Army. He is Star senior editor Debbie Kornmiller’s grandfather.

George Fines Mountain was born in Spilsby, Lincolnshire, on Sept. 28, 1889.

Before the war, George was working as a laborer.

During the war, he was a gunner for the Royal Field Artillery in the 134th Battery. His service earned him the Victory and British War medals.

His brothers, Henry and Norris, also served in the war. Henry Fines Mountain was a sergeant in 8th Battalion King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry. He died in Italy just before the end of the war on Aug. 30, 1918. Henry was buried in Dueville Communal Cemetery, Veneto, Italy. Norris also served in the battalion, signing up a decade before in 1905.

A search of Fold3.com, a sister site to Newspapers.com, both owned by Ancestry.com, found Granddad’s handwritten military records.

I know this is the second time I’ve mentioned “handwritten.” It’s so real to see handwritten documents, isn’t it? Granddad came alive again when I saw his name signed.

Fold3.com has digitized American military records dating back to the Revolutionary War, as well as British, Canadian and Australian records, Census records and city directories.

Included on the site was Granddad’s Medical Inspection Report:

He was 26 when he enlisted on May 19, 1915, and agreed to serve through the duration of the war. His qualification was cook.

He stood 5 feet, 6¼ inches tall. His girth (chest) measurement was 38 inches and his range of extension was 3 inches. Vision: Good. Physical: Good. He was deemed “fit.”

Included was a Certificate of Approving Officer, certifying that Granddad was “correct and properly filled up.”

Granddad’s military record shows that he was stationed at home from May 19, 1915, to Jan. 6, 1917. He was sent to France on Jan. 7, 1917, and served there until March 2, 1918. He came home on a 15-day furlough March 5 and returned to France on March 18. He stayed in France until May 8, 1919, apparently leaving the service on March 31, 1920.

The record shows that Pvt. George Fines Mountain was injured on Oct. 2, 1918, near Reincourt. The penetrating wound was to his right foot and was slight. The record notes that he was on duty and not to blame.

The statement of the accident, handwritten in my Granddad’s familiar hand, says that “at about 0900 on Oct. 2, 1918 at gun positions while engaged in chopping firewood a nail protruding out of the end of a piece of wood swung round and penetrated through my boot into my right foot.”

The New Zealand Field Ambulance attended and signed the statement.

George died in Doncaster, Yorkshire, in 1976 at the age of 87.

— Debbie Kornmiller, Arizona Daily Star

Flew the seaplanes, aka “strawberry crates”

My father, Edwin K. Bertine, left college early to serve in the Navy, and he became one of the early naval aviators who earned his wings at Pensacola, Florida, in 1918. Number 2115, actually, and he was commissioned an ensign at the same time.

He flew the seaplanes of the day, calling them “strawberry crates”; really designated HTA-1’s for “Heavier than Air.” They had a crew of three usually: pilot, co-pilot and foregunner — all open-air positions, of course, which they would rotate through in training.

The war ended before he and most of the aviators saw action in Europe; however, he almost succumbed to the Spanish flu epidemic that ran rampant universally in 1918. He was pulled out of the death ward by his college roommate and nursed back to health, and made his last flight in April 1919 (of which I have a faint photo taken in the air).

He returned to college and graduated in the class of 1918. When WWII occurred, he petitioned against the age limitation for service and was recommissioned. He served in the Aleutian Islands until the end of the war, having been designated commanding officer of the Naval Air Station on the remote island of Amchitka.

My father was always an inspiration to me. I served in the Navy as well.

— Peter K. Bertine

Won 2 gold medals in Inter-Allied Games

My father, Lt. Verle Campbell, U.S. Army platoon leader of a machine gun platoon, arrived in France about two days before the armistice was signed. He told us that he and a small group of other officers took a train to the front to get into the action before word reached them to stop fighting — thank God.

Verle Campbell arrived in France just before the armistice. He and others took a train to get into the action before the fighting ended.

Verle Campbell

As it turned out, they asked my father to stay in Paris for another six months, where he won two gold medals in the 1919 Inter-Allied Games. He won the 1600 relay and the medley relay in track and was presented these by the prince of Monaco and Gen. John “Black Jack” Pershing.

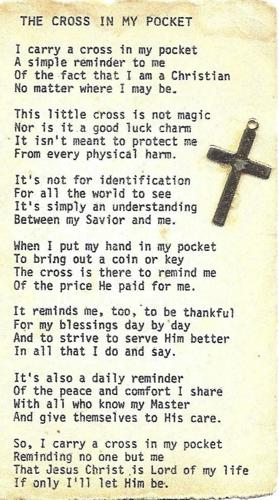

I sold his two Colt pistols and with the money set up a bank account for his four great-grandkids. What I did save were his picture, a Christian cross that he carried in his pocket and a copy of a memo he and many, many others received from the commander in chief of the American Expeditionary Forces, Gen. Pershing.

— Robert Campbell, former Army lieutenant, Green Valley

Gas poisoning eventually led to tracheotomy

My uncle, Ernest Werdel, was inducted into the Army on May 24, 1918, at Cleveland, Ohio. Although his service time was relatively short, he had a full range of experience.

Ernest Werdel served as a bugler. He saw action at Saint-Mihiel in the major offensive of Meuse-Argonne, where he was gassed.

After basic training, he was sent with his unit to France and served as a bugler. He saw action at Saint-Mihiel in the major American offensive of Meuse-Argonne, where he was gassed. The long-term effects of the gassing made it necessary for him to have a tracheotomy in later years. Upon reinstatement of the Purple Heart award in 1932, Mr. Werdel was one of the many World War I service veterans to receive this honor.

Following his discharge, Mr. Werdel worked as a messenger for Cleveland Trust Bank. He remained active well into his 90s and made a number of trips to Tucson to visit his family. He passed away in 1992 at age 100.

— Gloria Werdel Spies, Tucson

Purple Heart and World War I service medal earned by Ernest Werdel.

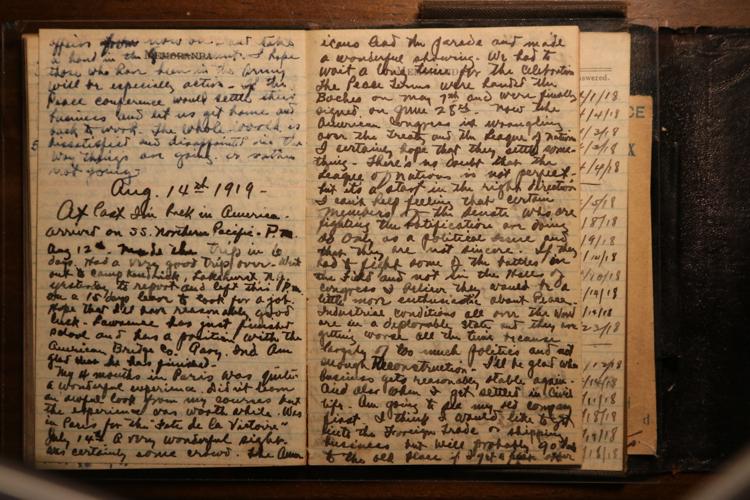

Diary reflects frustration with slow peace process

With a freshly minted degree in chemistry, my grandfather, Claude McLean, joined the Chemical Warfare Division of the U.S. Army in 1917 to train and equip soldiers to survive a chemical attack. He arrived in France on May 1, 1918. His diary reflects a combination of boredom (waiting for orders or supplies), terror (aerial bombardment, chemical attack, small-arms fire), sorrow (loss of a friend) and frustration about the endless fighting for no apparent purpose.

Claude McLean joined the Chemical Warfare Division of the Army in 1917 to train and equip soldiers to survive a chemical attack. He arrived in France on 1 May 1918

After the armistice on 11 November 1918, he longed to get home, but lack of ships meant he stayed in France until August 1919. His diary reflects his frustration with the peace process.

March 31, 1919: “The Peace Conference is still in session and nobody knows if they have done anything or not. The Russian, Balkans, Polish, and central European situation is still growing worse and Peace Delegates dilly-dallying along. It seems that none of them knows what we were fighting for or what they themselves want. I hope that at least a portion of our hopes for World Peace will be realized, but I really don’t believe that it is possible to prevent wars altogether. Adjourned without accomplishing anything, all politicians are doing nothing, criticizing, and playing Politics. But that’s the price we pay for Democracy. The Whole World is dissatisfied and disappointed in the way things are going, or rather not going.”

Diary of Lt. Claude McLean during his service in France.

Upon arrival back in the U.S., he turned his frustration on the government:

Aug. 14, 1919: “The Peace Treaty was handed to the Boches on May 7th and was finally signed on June 28th. Now the American Congress is wrangling over the Treaty and the League of Nations. I certainly hope that they settle something. There’s no doubt that the League of Nations is not perfect, but it’s a start in the right direction. I can’t help feeling that certain members of the Senate who are fighting the ratification are doing so only as a political issue and that they are not sincere. If they had to fight some of the battles in the field and not in the Halls of Congress I believe they would be a little more enthusiastic about Peace. Industrial conditions all over the World are in a deplorable state and they are getting worse all the time because largely of too much politics and not enough reconstruction. I’ll be glad when business gets reasonably stable again.”

Business didn’t become stable for him for some time. After jobs in Tennessee and Oklahoma, he moved his family to Phoenix in 1929. He lost his job due to the Depression shortly thereafter. Needing to support his family, he started his own business doing analytical chemistry, which eventually grew into three well-staffed laboratories in Phoenix, Tucson and Flagstaff. Claude McLean passed away at his home in Phoenix in 1973 at age 85.

— John McLean

Family received his Purple Heart 98 years later

Everett Peter Carney, of Auburn township, northeastern Pennsylvania, was called to service in the U.S. Army in the summer of 1918. He could have taken a deferment, being the only son of an elderly farmer, but said the other lads are going and so shall I.

Everett became a member of 304th Engineer Battalion, 79th (Cross of Lorraine) Division, shipped out for France and became part of the American Expeditionary Force.

The 304th, while participating in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, the largest offensive of the war, was caught in a fierce artillery barrage. Everett and many of his buddies were wounded. They couldn’t be recused at first because the Germans followed up with a gas attack. When the gas cleared, Everett was found to be still alive, but many others were dead.

He was sent to a Red Cross hospital and was released to head home in June of 1919. He led a quiet life, married Mary Allen, raised three children, and passed at 85, in December 1976. He never spoke of the war (only one time, when his son returned from Vietnam, he offered, but was turned down; he said he understood).

His granddaughter, Suzie Carney, at a Kings College reunion, telling her grandfather’s story to a classmate, now the under secretary of the Army (Pat Murphy), was informed that Everett may be entitled to a Purple Heart. They did some research and it was confirmed. In December 2016, the family received the Purple Heart and other awards 98 years later.

— Mike Carney

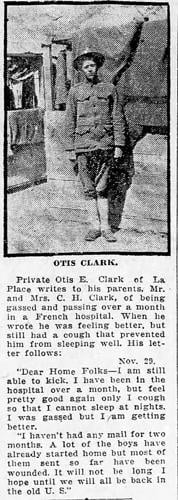

Otis Elmer Clark entered the service with the 129th U.S. Infantry. In November 1917, he was in basic training at Camp Logan in Houston, Texas, above. He was gassed at Bois Sachet in 1918.

Lung issues and “shell shock” lasted for years

My two grandfathers served in WWI.

Otis Elmer Clark was most likely born in 1891. He registered for the draft on June 5, 1917, in Macon County, Illinois. At the time, he was 25, married without children, and working as a farmhand in Mount Zion, Illinois.

He entered the military service in the 129th U.S. Infantry. In November of 1917, he was in basic training at Camp Logan in Houston, Texas. Army transport out of the county was provided on a ship named the Covington from Hoboken, New Jersey, on May 10, 1918. He and his fellow soldiers were then transported overseas. The 129th Infantry arrived in Brest, France, on May 23, 1918. The regiment disembarked at noon and made camp north of Brest, near Pontanazen Barracks. The regiment was put on lockdown after an outbreak of scarlet fever.

Otis Clark served until his discharge in 7 February 1919. [see exhibits 1 & 2] Throughout the years he was in and out of the hospital with lung issues and suffered from occasional bouts of anxiety and depression or “shell shock”.

On June 18, 1918, Co. B was entrained at Brest for Oismont, France. The regiment marched to Bethen on the 21st of June and was billeted overnight. On the 22nd they continued to march and arrived at Gorenflos. There they did regular camp duties, including drills and training. On July 6 the regiment marched to Vignacourt for maneuvers and then returned. By the end of July the regiment had relocated to serve with the 5th Australian Infantry. They dug trenches and provided trench support. The 129th relocated on Sept. 7-8 to relieve the 372nd U.S. Infantry. The sector had been quiet, but was now marked with increased enemy artillery and patrol activities. The regiment was put in the first wave in the sector from Forges to Malancourt on the night of the 25th, then moved by the 26th to the Rascasse Trench. They marched to Hill 281, and later to Bois Sachet and moved into the front line. On Oct. 5, 1918, they were shelled with yellow cross and phosgene gas mixed with shrapnel and helium. Otis was among those gassed. He was removed to the hospital to be treated.

Otis served until his discharge in February 7, 1919. Throughout the years he was in and out of the hospital with lung issues and suffered from occasional bouts of anxiety and depression, or “shell shock.” He died in 1976.

My other grandfather, William Adolph Skibbe, was born Nov. 3, 1890, in Chicago. He was the son of two German immigrants, Wilhelm and Julia (Panzer) Skibbe. William spent his younger years in Chicago. Later, his father moved the family to a farm in North Judson, Indiana.

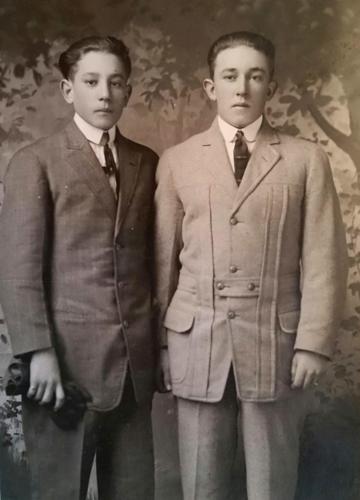

William A. Skibbe with his sisters Ruth, left, and Margaret in 1917.

His draft registration card was completed on June 5, 1917, in Wayne Township, Starke, Indiana. The draft led to his placement as a private in the Headquarters Company 47th Infantry. On May 10, 1918, he boarded the Princess Matoika from Hoboken, New Jersey, and sailed to France. The ship arrived in Brest, France, on July 16, 1918.

The 47th saw combat at Aisne-Marine, Saint-Mihiel, Meuse-Argonne, Champagne and Lorraine.

William A. Skibbe received an honorable discharge from the United States Army. William died on April 3, 1961, in Illinois.

— Amy Beth Urman, Tucson

Met his future wife while in training

Both my father and grandfather were in the service and overseas during the war, but not in the terrible fighting.

My grandfather, Alonzo C. Duddleston, born just before the Civil War, was the captain of a Terre Haute, Indiana, infantry unit that was sent to France. Apparently, because of his age (and, I suppose, physical condition), the Army relieved him of his command and sent his men into battle.

Alonzo Coltrin Duddleston

Charles S. Duddleston trained as a fighter pilot .

My father, Charles S. Duddleston, born in 1892, was a graduate engineer working for an electric company. He enlisted in the Army and was trained as a fighter pilot. He first was an officer-instructor in the U.S., but was then sent to England on a mission studying British airplane production. He was in France only briefly, but not in aviation. While training in San Diego, Charles met my mother, Lucille Reid, a teacher and a graduate of a San Diego normal school. They were married soon after the war.

— Thomas C. Duddleston, Tucson

Franklin Fredrick Schanke’s foot locker.

Sewed seatbelts to secure pilots in open cockpits

My father, Franklin Fredrick Schanke, was born in Indianapolis, Indiana, in March 1890, the 11th son in the family. His parents were both immigrants from Prague and southern Germany; they met on the sailing boat that brought them to the United States during the Civil War.

My father graduated from the eighth grade when he was 13 years old. To learn a trade, he moved to Detroit to train as an apprentice automobile upholsterer. Within a few years, he became a journeyman. He said at the time if you were old enough to grow a mustache (which he did at 16), you were old enough to buy a beer, for a nickel.

Franklin Schanke sewed seat belts for aviators.

When World War I started, he contacted the U.S. Army recruiting office and volunteered. When asked by the recruiter if he thought he could sew coverings for aircraft, he replied that he could sew anything. He signed the paperwork and was shipped off to a six-week technical school that taught him the skills needed to cover and dope airplanes.

He was shipped to San Antonio, Texas, to Kelley Field for his first assignment. He was part of the U.S. Army Signal Corp, which at the time owned the fledgling Army Air Corp. The aircraft he worked on were mostly JN-1 (Jenneys) and Spads.

He talked about spending lots of time working with leather to sew seatbelts used to secure the pilots in the open-cockpit aircraft. Someone decided they were necessary, as a few pilots fell out without being secured.

He was frequently tasked with guard duty overnight. The guards were issued tent stakes in place of rifles, as the Army was afraid they would shoot someone.

He also talked about the food. He retained a dislike of lamb because of the frequent servings of poor-quality canned lamb that earned it the title of “Canned Woolly”.

I am proud of his service and of his memories.

— Kenneth F. Schanke, major, USAF (retired), Tucson

Lost a lung to mustard gas; buried at Arlington

I am writing about Neil Bigelow, my grandfather on my mother’s side.

He served in France in WWI, but his military career was cut short due to mustard gas poisoning. He survived, but lost a lung and was left physically stressed for the rest of his life. He died at age 68, and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery as a private, (which must say something about his service record, as it does not happen easily).

Neil Bigelow was poisoned by mustard gas in France. He died at age 68 and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery as a private.

Due to growing up on separate coasts, I did not get to know him well, as he passed away when I was only 22. Grandpa was a kind but stern man, as were most who experienced war and the Depression. I wish we could have known each other better.

— Frank Engle, Oro Valley

Two bullets remained in his lower back

My grandfather, Cecil Laurence Cripe, was a gentle and kind man. He was a poet and a graduate of Ames University, Iowa. In 1917, at age 19, he answered the call for Americans to respond to the war in Europe. Joining the U.S. Army, he left his home in Missouri.

On Sept. 26, 1918, my grandfather took part in the massive Meuse-Argonne Offensive in France. On that day, while advancing with his unit in some picturesque hillocks, he was hit just above the belt-line by a burst of bullets from a German machine gun nest. He went down among other wounded colleagues and was fortunate to get help that evening and taken to the rear for a long convalescence. Several of the rounds that hit him lodged near his spine and could not be removed without the risk of paralysis. Lucky to be alive, he underwent surgeries and therapy that eventually rendered him capable of helping other wounded soldiers.

Cecil Laurence Cripe left on a troop ship on February, 1918 as part of the U.S. Expeditionary Forces.

After his service, my grandfather copyrighted a song entitled “Our Uncle Sam.” Like many veterans, he did not speak of his experiences in war. He did, however, show me and my brother the two discolored areas in his lower back that represented the locations of the two bullets that could not be removed during World War I. Those two bullets remained with him when he was buried, in 1964.

— Laurence Grant Cripe, Tucson

Visited by Pershing while in hospital with skull fracture

Charles J. Fahey was a lieutenant in World War I, where he was awarded the Purple Heart. At the age of 22, he joined the U.S. Army the day after President Woodrow Wilson declared war. He was given the Army’s General Intelligence Test and sent to Officers’ Training School. He was commissioned as a first lieutenant in the Ohio Pioneer Regiment.

He and his fellow soldiers arrived in France about four months before the war ended. Some time after his arrival, his unit was under German fire and he was given orders to go back to headquarters to get more firepower and replacements for the Pioneer Regiment unit. Lt. Fahey was driven in the sidecar of a two-man motorcycle. In the pressure of the moment, the driver hit a tree stump, throwing the lieutenant out of the sidecar and knocking him unconscious.

Charles J Fahey was a lieutenant in World War I and was awarded the Purple Heart.

He remembered nothing more until he woke up in a French farmhouse. These farm people found Fahey and the driver injured and brought them inside the house to nurse them through their injuries. The young officer complained of terrible head pains, and when the Army medical people found them in the farmhouse days later, the two injured soldiers were taken to the nearest American military hospital to recuperate for several months. Fahey was found to have a fractured skull.

After some weeks in the hospital, the wounded and injured men were visited by Gen. John “Black Jack” Pershing, supreme American commander in World War I. Pershing stopped at each bed and greeted each man. When he got to Fahey’s bed, Pershing asked how he was doing, shook his hand and wished him well.

What hasn’t been mentioned is that the Ohio Pioneer Regiment was mostly made up of African-American men. The Army remained this way until President Truman ended segregation in the military. This had to have a profound effect on Charles Fahey, as he grew into a man who had empathy for the underdog. He never used or allowed to be used any slurs about any group or individual. He was incensed by the internment of Japanese-Americans during WWII. He certainly was ahead of his time.

— Dan Fahey

Career dream led to “just sign here,” nearly fatal flu

Harold J. Dorschner hoped joining the Army in 1917 would give him a career boost that otherwise seemed largely unattainable. When the United States entered World War I in April 1917, Harold was a 20-year-old laborer working for his father maintaining a stretch of track for the Chicago & Northwestern Railroad near Brillion, Wisconsin. One of Harold’s friends told him about the Army Railroad Corps, and dangled the bright prospect of joining the Army and becoming railroad engineers, driving shiny black engines, one hand on the throttle, the other ready with the steam whistle.

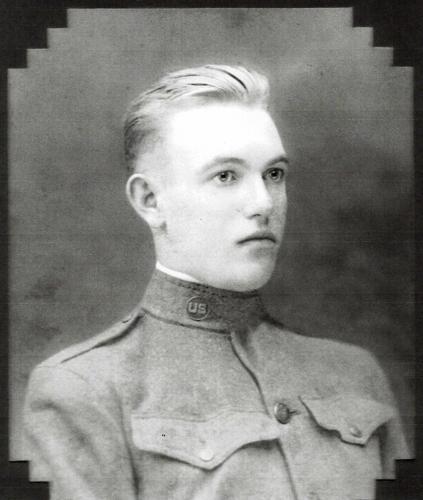

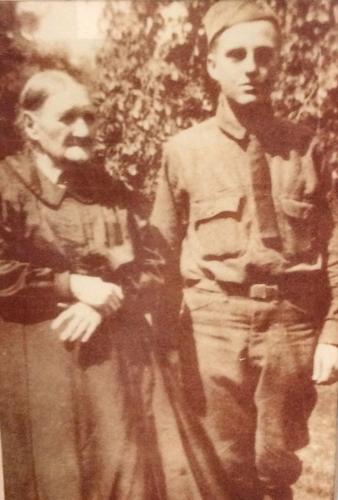

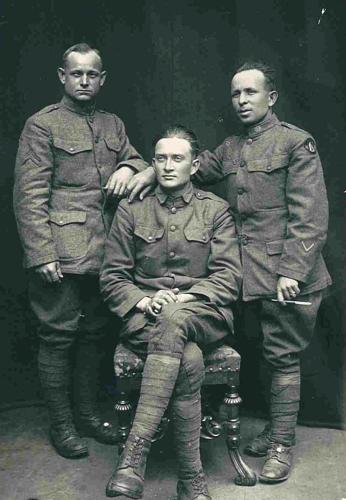

Harold and Wilbur Dorschner in 1917. Harold entered the service with the promise of being a railroad engineer, fixed tracks instead.

When the two of them finally met an Army recruiter, he briskly assured them of a place in the prestigious Railroad Corps, you bet: “Just sign here boys.” Of course, after a few months of basic training at a hastily built camp near Chicago, Harold actually ended up as an infantryman with Company C of the regular Army 9th Infantry Regiment, on its way to France in early October 1917 in one of the first troop ship convoys carrying doughboys across the Atlantic.

In the 2nd Division, the 9th Infantry and the 23rd Infantry constituted the 3rd Brigade. The 5th and 6th Marine Regiments were 4th Brigade. Initially, Marine Corps Brig. Gen. Charles Doyen commanded the division, but was replaced by Army Maj. Gen. Omar Bundy. Following a period of pre-combat training at Bourmont, the 9th Infantry spent much of that winter in a quiet section of the French line, including special fatigue duties such as repairing railroads, which must have really chapped Harold, the would-be engineer. These months also involved familiarizing with the modern weapons and tactics developed by the Allies since 1914 and gaining combat experience through frequent raids into German-held territory.

Finally, on March 17, 1918, the 9th Infantry moved into an active portion of the front lines near Verdun in the Troyon-Toulon sector. On March 21, the Germans launched the massive Operation Michael offensive along the British-held front in the Somme Valley with three armies, which broke through the British Fifth Army, advancing up to 40 miles and destroying 15 British divisions.

While French and British forces eventually stabilized the lines, a second German offensive on April 9, 1918, against British forces in Flanders forced another British retreat and major adjustments to Allied lines. In response, the commander of the American Expeditionary Force in France, Gen. John Pershing, agreed to rush several divisions into the line under French and British command, including the 2nd Division.

Meanwhile, in the Verdun area, the 9th Infantry had already taken casualties while enduring German artillery fire, snipers, bombing raids, gas attacks and raiding parties. At the end of March, the 9th Infantry occupied trenches near the town of Saint-Mihiel, with the Meuse River behind them and the 23rd Infantry on their right. Thereafter, the 9th Infantry spent 152 days in combat, suffering a total of 4,571 killed, wounded and captured, equal to over 100 percent of authorized strength. Harold and the rest of the 9th Infantry Regiment ultimately fought in most of the major American battles in France, including Soissons, Saint-Mihiel, Blanc Mont and the Meuse-Argonne Offensive that ended the war. The 2nd Division ended the war with the dubious honor of being the most active of the 45 divisions in the AEF.

After the armistice in November 1918, Harold, still a private, remained with Company C on Allied occupation duty along the Rhine River in Koblenz, Germany. At Koblenz in early 1919, Harold contracted influenza and nearly died. Along with thousands of other soldiers, he was evacuated to the United States aboard a hospital ship and mustered out of the Army, back in Wisconsin, in May.

Harold Dorschner with his wife, Clara, on their wedding day 1920.

Harold very rarely ever mentioned the war. On one occasion in 1965, speaking to grandson Jim, he mentioned “getting gassed and killing some Germans” and described with great detail a visit to the front by a Red Cross doughnut truck staffed by American girls, and how strange it was to see them there, and how good the coffee and doughnuts were.

Harold went back to work for the Chicago and Northwestern Railroad. He retired in 1964 and died in Manitowoc, Wisconsin, in 1981.

— Jim Dorschner

Went to Mexico under “Black Jack” to fight Villa

My father, Reuben D. Amos, was a WWI veteran. He enlisted June 19, 1916, in Warren, Ohio. He served in Company D, 5th Infantry Ohio National Guard, beginning as a private and being promoted several times, becoming a sergeant in 1918.

He went to Mexico in 1916 to serve under Gen. John “Black Jack” Pershing to help unseat Pancho Villa.

He received orders to go overseas to fight in WWI and wanted to marry my mother before he was shipped out. He told her that the only way he could get a furlough would be if he were going to be married, so she relented, only to find out later that that was not true.

Reuben D. Amos was sent to France where he served in the area of Flanders, Verdun, and was wounded and gassed at Meuse-Argonne on September 28, 1918.

Following their marriage on May 4, 1917, in Stark County, Ohio, he was sent to France, where he served in the area of Flanders, Verdun, and was wounded and gassed at Meuse-Argonne on Sept. 28, 1918. He received an honorable discharge on March 29, 1919, in Sherman County, Ohio, with 15 percent disability. He received the Purple Heart for his service.

— Bonnie Amos Logan

Helen Duffy, 2, went to stand next to her uncles, Rob and Lawrence Duffy, when they gathered with a group of other soldiers getting ready to ship out from DeKalb, Illinois, in 1918.

2-year-old girl posed with soldiers heading to war

I have a picture that has been in our family for over 100 years. It shows a group of soldiers in front of the courthouse in DeKalb, Illinois, in 1918 getting ready to head to fight in World War I. But a little girl of about 2 wanted to be near her uncles Rob and Lawrence Duffy, so she wandered into the picture. Her parents were going to get her out, but the photographer said, “Let her stay.”

So here’s this little girl in a sailor’s suit with about 60 GIs. The little girl eventually became my mother, Helen. This picture made its rounds at a lot of family celebrations.

Both Rob and Lawrence survived their trip overseas. My mother died in 2017 at age 101.

— Father James W. Modeen

Finished high school after serving in the war

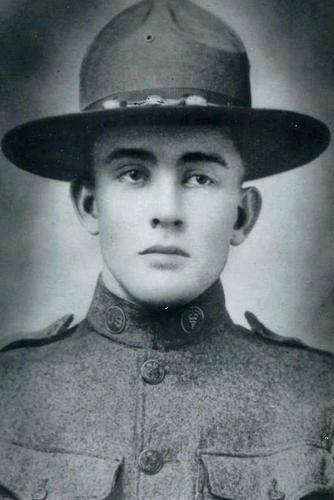

John Coyle, with his grandmother in 1917, left high school at 17 to fight in the war. He finished his diploma after he returned.

My grandfather, John Coyle, left high school during his junior year, age 17, to join the Army and served in France as a private first class, leaving only subsequent to the 1918 armistice. Upon being discharged from the service, he went back and finished high school in Galva, Illinois, where he lived the remainder of his 77 years.

— Tim Colbert

Steps up the Eiffel Tower retraced by grandson

A picture of my father, Wesley C. Tilson, was taken in Paris in 1918. He enlisted in the Army on Dec. 10, 1917, into the 20th Engineers, assigned to 25th Company (later Company A) 9th Battalion. The unit was assigned to Epinal District in France. He was discharged on June 12, 1919. He returned home to Rudyard, Michigan, where he spent the rest of his life as the town barber.

He climbed the Eiffel Tower while in Paris, and some 60-plus ears later, my son, Greg Tate, who was stationed in Germany with the Army, climbed it in his honor.

— Frances Tate, Tucson

Harry Patch, second row, center, in France in 1918. He was gassed during the fighting and had weak lungs and a slight cough for the rest of his life. He retired in Tucson and died at the Veterans Administration Hospital in 1955.

Always marched in Armistice Day parades

My father, Harry A. Patch, was born on Nov. 20, 1886, and was descended from the first Patches to immigrate to America from Scotland, on one of the Mayflower trips (not the first one).

He enlisted in the U.S. Army on Dec. 12, 1917, and was honorably discharged on July 12, 1919. He was 31 years old when he enlisted. We come from a long line of very patriotic citizens, and the first thing he thought of when he heard of the war was that he had to serve his country.

He became a sergeant and had his own group of men once he arrived in France. Harry was gassed on the battlefield, and as a result, had weak lungs and a slight cough for the rest of his life. My father didn’t talk about the war much, and I always felt that he didn’t want to discuss the battles.

Sgt. Harry Patch, France, 1918.

For years afterward, he always marched in the Armistice Day parades in downtown Omaha, Nebraska, while my sisters and mother and I proudly watched.

After the war, he worked until retirement at the Omaha Electric plant. He retired in Tucson and passed away at the veterans hospital here on March 14, 1955. He was my hero, and the best father who every lived.

— Cherie B. Shaw, Tucson

Underweight, he ate pies, bananas until he could serve

My father, Rufus Malcolm Orr, was born in Enfield, Illinois, in 1894.

He used to tell this story: When the war broke out, he had just finished college. He was about 5-foot-6 and probably didn’t weigh much more than 100 pounds. He went to the Navy recruiting office and was told that he didn’t weigh enough, so he returned home, ate many bananas and pies and drank gallons of milk, and returned. They told him he still was underweight, but they would take him.

His basic training was at Great Lakes. Eventually, he was assigned to the Dental Corps and was stationed in Norfolk, Virginia. He was stationed there when the Spanish influenza broke out.

He kept hearing about all the “boys” dying of the flu, so one day, while off duty, but still in uniform, he decided to go to the hospital ward and see for himself what was going on. He poked his head into one ward after another only to see in every one of them numerous beds with sailors in bed with sheets pulled up over their heads. Just at that time, a nurse down the hall spotted him, and thinking that he was a hospital corpsman, called, “Corpsman!” wanting his assistance. He took off running and never went back.

After his service, he practiced dentistry in the St. Louis area until he passed away at 87. I was proud that he served and I think he was one lucky guy.

— Sue Martens, Tucson

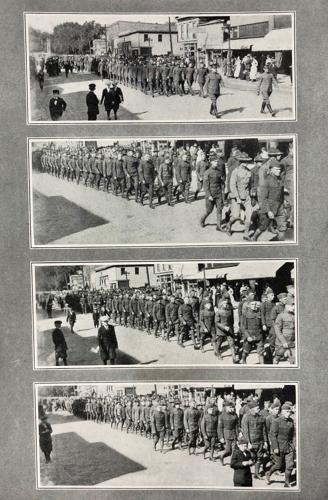

A homecoming parade in Livingston County, Illinois, in October 1919.

Memory lives on through photos, stories

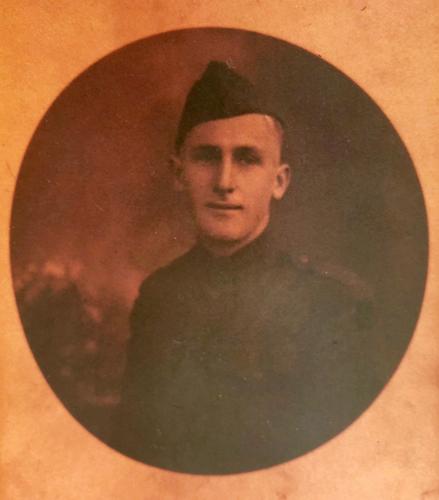

US Army enlistment photo of Sidney F. Call, 1917.

My grandfather, Sidney Call, served in the U.S. Army from 1917 to 1919. He served in World War I from May 1918 to November 1918. After returning home in the summer of 1919, he married and started a family. My grandfather passed away 10 years before I was born, so I never had the chance to know him personally, but his memory lives on through photos, media, and stories of his life.

— James Call, Tucson

Pacifists helped create conscientious objection option

My grandmother, Margaret Shetler Kaufman, told stories from WWI that differ substantially from most of the stories submitted for this project, I’m sure. My family was “Pennsylvania Dutch” Mennonite in the coal mining country around Johnstown, Pennsylvania. As Mennonites, they were pacifists, and also as Mennonites they were bilingual German-language speakers even though they arrived before the United States was even a country.

With two strikes against them as pacifists who refused to join the military and as immigrants who still spoke German, Mennonites were a target of suspicion and jingoistic patriotism while the country was at war. To make matters worse, my grandmother’s father, S.G. Shetler, was a prominent Mennonite bishop. My grandmother was a schoolgirl at the time of the war and she said that people would throw eggs at her and her sister and brothers as they walked to and from school. Her father received a weekly visit from the FBI. She said once a lynch mob showed up, complete with a rope noose. Fortunately a visiting Protestant pastor was able to talk the men out of hanging my great-grandfather, but it was a near thing.

The United States was only in the war for 18 months, but in that time the German-language press in this country was decimated by lack of advertising and distrust of anything German. It never did recover.

There was also no conscientious-objector status to the draft in WWI, so Mennonite boys, Church of the Brethren, Amish, Jehovah’s Witnesses and other pacifists were drafted but refused to fight. They were both prosecuted and persecuted. My grandmother told stories of imprisonment of these young men.

Following WWI, my great-grandfather was one of three Mennonite bishops to travel to Washington, D.C., where they enlisted the support of the head of the Selective Service for what we have today as the conscientious objection deferment to the draft. A hundred years later, only the stories remain, but they happened to real people just like us.

— Chuck Kaufman, Tucson