On Nov. 11, 1918, the bells pealed at the unfinished Santa Cruz Catholic Church. The sound resonated across the nearly empty land around it and the more populated downtown.

When Tucson Bishop Henry R. Granjon received the news that an armistice had been signed and the First World War had come to an end, the head of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Tucson rushed to the church, went up the tower and rang the bells.

Even before the church, south of downtown, was consecrated and opened its doors to worshipers, Santa Cruz, with its iconic tower at the southwest corner of West 22nd Street and South Sixth Avenue, has played a role in the lives of many Tuconenses. And to honor that role, beginning in February 2019, the parish will kick off a year-long celebration of the church’s centenary.

The church includes a sanctuary, an inner courtyard, walkways, arches and fountains surrounded by a high wall.

“The church brings us all back together. It’s a beautiful white symbol,” said retired teacher Penny Green Cardenas, a lifelong parishioner who volunteers as a religious education teacher.

For many Tucson families, the church has been a central fixture in their lives.

Generations have been baptized, married, and given their final celebration of life with a funeral. In addition, the church has maintained its school, educating scores of students, and its fiestas have attracted people from beyond its south-side neighborhood.

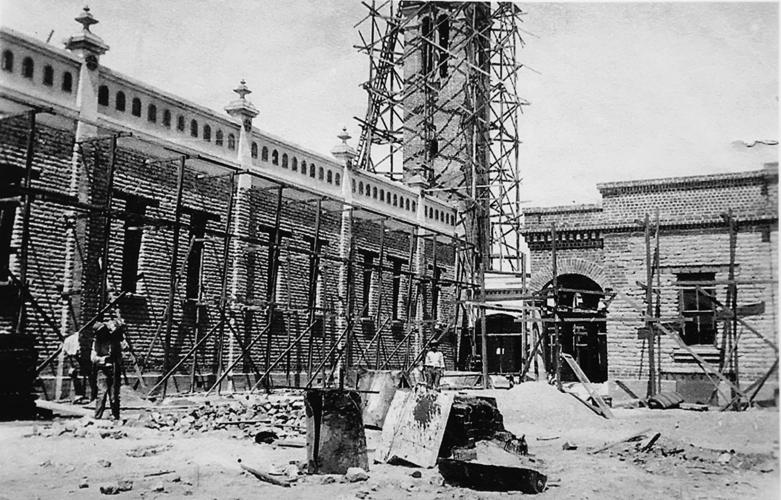

Undated photo of Santa Cruz Catholic Church, 1220 S. Sixth Avenue in Tucson, AZ. The church was built between 1916 and 1918.

“It has a cultural significance for the entire community,” said Antonio Barrios, the church’s former choir director, whose family has been connected to Santa Cruz Church since 1922, three years after it opened. “Its presence has affected people’s lives one way or another.”

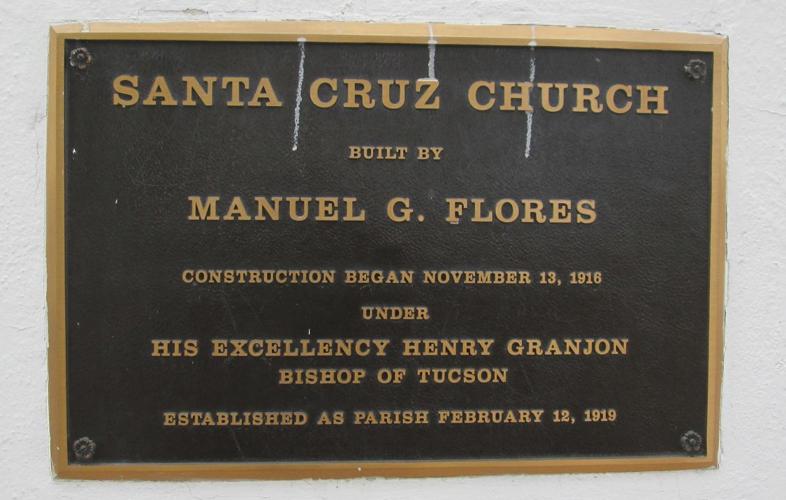

Construction of the adobe church began in 1916, during World War I. Granjon, the diocese’s second bishop, designed the Spanish-revival church, which was built by Manuel G. Flores. The mud bricks in the 22-inch thick walls came from the Tohono O’odham Reservation.

The church includes a sanctuary, a monastery for Carmelite friars, an inner courtyard, walkways, arches and fountains surrounded by a high wall. Its signature 90-foot tower resembles a minaret, reflecting the Moorish Arabic influence on Spanish architecture.

Santa Cruz was Tucson’s third Catholic Church, following San Agustín, the first, and Holy Family, which opened in 1914 north of downtown in the Dunbar Spring neighborhood. Santa Cruz is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Michael Gonzales paints the mural above the altar at Santa Cruz Catholic Church as he works late into the evening in 2009. In February, the parish will begin a yearlong celebration of the church’s centenary.

But Santa Cruz, Spanish for Holy Cross, is more than the historic building, said the Rev. Jose Luis Ferroni, one of four Carmelite friars assigned to the church.

“I look at it not as a building but as a fountain where families have grown,” said Ferroni, a church historian who is spearheading next year’s 100-year celebration.

Not only did it serve as a religious center, but Santa Cruz Church has been a cultural and educational center as well, said Ferroni, an ex-Navy corpsman who served in the first Gulf War. The church, when it opened, was essentially the only church with a parish stretching south to the U.S.-Mexico border, he added.

In addition to serving as a community beacon, Ferroni, who was born in Mexico and grew up in Florida, said Santa Cruz was an important hub for the Discalced Carmelites, who arrived in Arizona in 1911, a year before statehood. The brown-robed Carmelites have ministered from the church since its birth.

Generations have been baptized, married and had their funerals at the church.

Ferroni said that from 1924 to 1956, the Carmelites at Santa Cruz published and printed a monthly Spanish-language magazine that circulated here, as well as in Mexico, Latin America and Spain, where the order was born. A trove of photographs of the church and its community are archived at the Arizona Historical Society, he added.

Santa Cruz Church also boasts the unique distinction that five Carmelites, who at some point were assigned to Santa Cruz and later killed in Spain during the 1936 Spanish Civil War, have been beatified as martyrs by two popes, a step toward sainthood.

Ferroni, who was first assigned to Santa Cruz in 2007 and returned in 2017, said the church has changed, as its parishioners have become more involved in the church’s administration.

“They have taken ownership of their own parish,” he said. “They see the clergy as their equal.”

As Santa Cruz moves into its second 100 years and meets the challenges of the modern Catholic Church, it will always have its rich history to guide it. It’s a history strengthened by families, their relationships with the priests, and their collective faith.

Painter Ramon Lujan prepares to cover a stained glass window with plastic in the reconstructed Santa Cruz Catholic Church on Monday, July 20, 2009. The historic church was closed for repairs for most of that year. The roof and ceiling were removed and replaced because of structural problems with the support tresses.

Undated photo of Santa Cruz Catholic Church, 1220 S. Sixth Avenue in Tucson, AZ. The church was built between 1916 and 1918.

Undated photo of Santa Cruz Catholic Church, 1220 S. Sixth Avenue in Tucson, AZ. The church was built between 1916 and 1918.

Undated photo of Santa Cruz Catholic Church, 1220 S. Sixth Avenue in Tucson, AZ. The church was built between 1916 and 1918.

Undated photo of Santa Cruz Catholic Church, 1220 S. Sixth Avenue in Tucson, AZ. The church was built between 1916 and 1918.