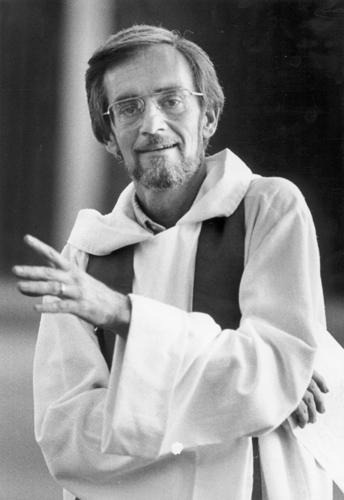

When the Rev. John Fife arrived at Southside Presbyterian in 1969 as the new pastor, he told the congregation that he never saw a church wear out its facilities. “But we’re going to do that in the next few years,” he told the congregation.

“And we did,” Fife said last week.

In the subsequent years the multiracial and multiethnic congregation expanded, as did its ministries focusing on social justice and humanitarian work. Southside built a new church, called the kiva and added space to its campus at West 23rd Street and South 10th Avenue, in a low-income barrio adjoining South Tucson.

Fife stepped down as Southside’s pastor in 2005, but the congregation continued expanding its mission and ministries, fulfilling his 1969 prescient words about wearing out the church. Today not only is Southside worn out, it’s run out of space, which is used full time by the congregation for prayer and Bible study, and by community groups including Cross Streets Community, which serves the homeless, Samaritans who provide assistance to undocumented border crossers in the desert, Southside Workers Center, Paisanos and Keep Tucson Legal Clinic, which work with immigrant families. Southside even provides worship space for a small congregation of Seventh Day Adventists.

“This place has been worn down to make Tucson a better place,” said the Rev. Alison Harrington, who succeeded Fife as Southside’s pastor in 2009.

To expand its facilities, Southside is engaged in a $1.7 million capital campaign to build a new commercial kitchen, additional classrooms, a new fellowship hall, library and parking lot, a main entrance, and enhancements of the interior courtyard and outdoor gathering space, including a mediation area in the new parking lot.

As part of its fundraising effort, Southside will celebrate the 50th anniversary of Fife’s ordination ceremony on Nov. 18 in honor of his work, which elevated Southside Presbyterian into a nationally recognized congregation for commitment to its Christian values of helping others in need.

Southside is best known for being at the forefront of the international Sanctuary movement in the early 1980s, when thousands of Central American refugees fled persecution and political violence in Central America. Again, in the latter years of the Barack Obama presidency as immigrant families were being separated under increased deportations, Southside resurrected sanctuary efforts.

“It means everything to me today,” said Patricia Barceló, who fled Guatemala with her family in 1985 because of political persecution. Southside gave her and her family — parents, grandmother and two siblings — new life.

Barceló’s family, as well as many others, found refuge within Southside’s buildings.

“A day doesn’t go by that I don’t give thanks,” Barceló said.

Southside’s walls and history are rooted in welcoming and embracing families who were rejected elsewhere.

It was founded as a church for Tohono O’odham who left the reservation and came to Tucson for work and better opportunities. The first O’odham in the congregation worshipped under a tent in the early 1900s. They could not worship elsewhere. In 1906 a small sanctuary was built out of adobe, but it later burned down. Portions of its walls remain.

Debbie Bergman’s O’odham grandparents, who raised eight children, were one of Southside’s founding families. Her grandfather bought a small plot across the street from Southside where the family found spirituality and security.

“Their lives were surrounded by the church,” said Bergman. “And it’s still a focal point for my family.” Her sister kept their grandfather’s house and members of Bergman’s extended family continue to attend services at Southside.

Southside is a small church, but its doors are wide. It is a safe anchor in the barrio and a moral beacon for Tucson.

“The church has always been shaped by what was happening in the barrio,” Harrington said. “We’re creating space for people to gather; we’re creating space for justice.”

A successful building campaign will ensure that Southside will continue its mission in support of social equity and community involvement.

“When they complete the project, the mandate is going to be the same,” Fife said. “We’re going to wear it out.”