The words were chilling and harrowing, even when their authors read them calmly in matter-of-fact voices. The writers provoked images of despair and suffering that they had experienced directly.

“The Gestapo and SS came immediately after the German army, and the persecution began. My uncle, Israel Lichter, was dragged away and put in a converted enclosure along with many single young Jewish men. They were all tortured and murdered,” said Pawel Lichter.

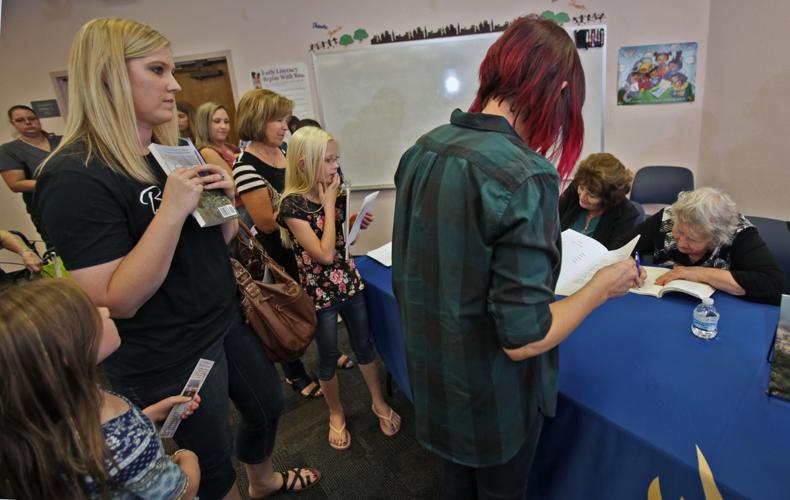

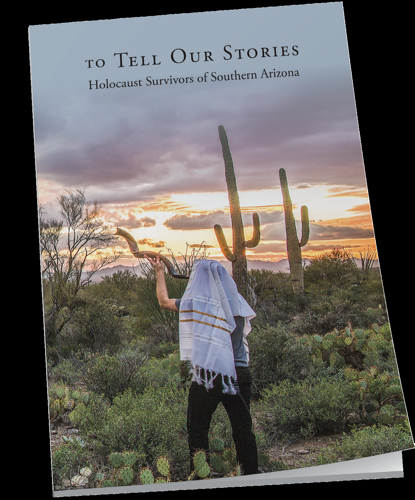

Lichter, who was born in Poland, was one of five witnesses of the Holocaust who told their stories Monday, Nov. 6, at the Nanini Library on North Shannon Road. They read their own words from the book “To Tell Our Stories: Holocaust Survivors of Southern Arizona,” a collection of 36 stories published in 2015 by the Jewish Family and Children’s Services of Southern Arizona.

The book evolved from the work of Raisa Moroz, a program director at Jewish Family, who works with Holocaust survivors. A refugee herself from Belarus of the former Soviet Union, Moroz began urging her Russian-speaking clients to write their stories. Richard Fenwick, a volunteer at Jewish Family and a retired U.S. Air Force Russian translator, stepped forward to translate the stories into English and transcribe recorded stories. The project expanded to include stories in English from Western European survivors.

“I believe it is important for people to know what happened years ago and from the people who experienced what happened,” said Moroz, whose family fled in 1996 because of anti-Semitism in the former Soviet Union.

“Eventually, more anti-Jewish laws came about. One made all Jews wear the yellow star. Another called for all Jews to be concentrated into one neighborhood, to move into ‘Jewish Houses,’ or as they were called, ‘Star Houses,’” Erika Dattner read in her testimony to the small library audience.

Dattner survived the war hiding under an assumed name, with the help of Protestant clergy, in Budapest, Hungary. Her father was forced to work as a laborer, and her mother used false identification to work as a maid. After the war, Dattner immigrated to Palestine in 1947 and 10 years later arrived in the United States.

Hearing directly from the survivors takes on greater importance because of the fact that there are fewer and fewer survivors. Moroz said of the original 36 survivors who contributed stories to the book, 12 have died.

Overall, she said, there are close to 100 survivors in Tucson and she estimates a total of about 250 live in Southern Arizona. She said a second book, containing 40 new stories of local Holocaust survivors, will be published next year.

Wolfgang Hellpap was born in Berlin in 1931 to an unmarried couple, a Jewish father and a Christian mother. He said he first experienced anti-Semitism when he entered school.

“I made it to the second grade before they found out I was officially Jewish. They kicked me out of school in the middle of class, when the teacher said she had my name on a a list and told me to leave. That was the law. All of a sudden the other kids were throwing rocks and spitting at me, so I had to run as fast as I could. I was crying.”

With his father gone and his mother unable to care for him, the young Wolfgang was on his own, hiding, living with family members until he was discovered by the Gestapo. He was placed in a children’s Jewish camp — where some of the Jewish teachers cooperated with the authorities.

He survived and immigrated to Palestine when he was a teen. He served in the Israeli army and came to the U.S. in 1955.

Moroz said that the survivors who are included in the book have told their stories to schoolchildren and community groups. And there will be more public readings from the book in the coming months.

But Lichter began publicly sharing his stories only a couple of years ago. He realized people needed to hear them.

“We don’t want it to happen again,” said Lichter, who fled Poland with his family after the German invasion and settled in Uzbekistan. After the war he returned briefly to Poland, then immigrated to Mexico in 1947 where he lived for 10 years before immigrating to the U.S.

While he is willing to share some of his stories, Lichter, 86, said there are still some he harbors, too horrific to retell.

“It’s depressing,” he said. “There are stories like that.”

Pawel, like his fellow survivors, asks that we read their stories and those of other Holocaust survivors to understand that genocide has and continues to plague our world.

“Things like that shouldn’t happen anymore,” he said. “We need to have consideration for other people who realize that we’re all human.”