The last time Joel Moreno saw his longtime friend, Jose Manuel Quero, they talked in the morning like they did every day for the past 20 years. When their daily chat ended, Quero asked for 10 bucks, which Moreno gave him, like he always did when Quero asked.

Quero then walked off to do his daily thing. His routine was to hang around the intersection of South 12th Avenue and West Irvington Road, stand at the corner, wave to motorists, walk up and down the two main streets, visit friends in the stores and businesses, talk to strangers who happened to pass by or greet people he knew who stopped to say “hi.”

He made that intersection the focus of his life, and it turned out to be the place he lost his life.

Quero was walking in the crosswalk about 10 p.m. Saturday, Feb. 4, when a taxi, westbound on Irvington, struck him. He died later at a hospital. He was 63.

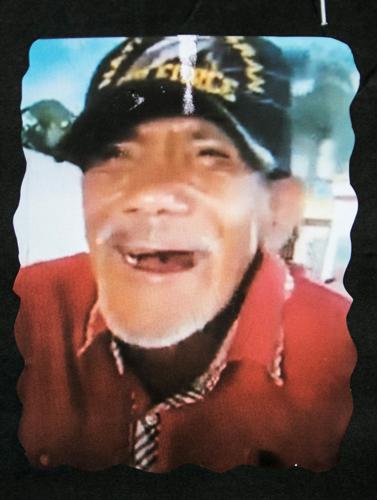

It seems that anyone and everyone who lived and worked in a several-block radius of the intersection knew Quero, or as his friends called him, “El Chaka.”

“He was a south-side legend,” said Bobby Chambers, a barber at Henry’s Barber Parlor on South 12th. Quero, who talked in a raspy voice and loved to shadowbox, would walk in and shoot the breeze with Chambers, fellow barber Paul Nogales and shop owner Henry C. Paredes.

El Chaka was everyone’s friend. If he bummed a dollar off of you, he’d pay you back. If you asked him for a dollar, he’d give it to you without expecting he’d get it back. He ate at the small restaurants and taco carts near his perch, where he had credit.

Manny, as he also was known, “remembered everything, man,” said Rene A. Moreno, Joel’s nephew.

Quero would pay everyone back when his Social Security checks came in, said Joel Moreno, who managed Chaka’s money and knew him since 1991. Quero lay his head first in a trailer, and later in a small house behind Moreno’s business, All Star Window Tinting on South 12th.

He was familiar to everyone for his smile, his laughter, his loyalty and his affection for children, to whom he would give a dollar if he had one in his pocket.

But Quero, a military veteran who immigrated from Mexico City and lived in California before coming to Tucson, fought his demons. He was an alcoholic and battled mental issues, his friends said.

“He was a little bit off,” said Nogales, the barber, “but he was cool.”

Tucson police said the taxi driver, who had the green light when he drove into the intersection, exhibited signs and symptoms of impairment and a DUI investigation was conducted. Police investigators had not released additional information as of Friday.

Three days after his death, I stopped at Chaka’s corner. An altar had been created with candles and photos of him. A blue quilt lay on the sidewalk where people wrote their condolences with a black marker, and empty cans of Bud beer completed the tableau.

His son, Edgar Quero, was standing there. But he wasn’t alone. In the few minutes that we talked, people drove up, got out and paid their respects to his father.

One of the many was David “El Real” Ochoa, one of Quero’s younger street-running buddies. Luis Ramirez and Rosana Luque also stopped. Martin Suarez, who works at Pepe’s and Sons Tire Shop on South 12th, also visited the impromptu shrine. They all had good words and thoughts about Chaka.

And so it went all week.

Daniela Verduzco Montijo, who works at Title Max Title Loans on the southwest corner of the intersection, would see him every day. But she didn’t realize how popular he was until the altar sprouted.

This outpouring of affection and sadness speaks to Chaka’s appeal and humanity. He was loved.

“He was a great man. He had love for everybody,” said the homie, El Real. “He had problems but he was a good man. He helped out everyone.”

Apparently he helped everyone but himself.

“I tried to get him to quit, but I couldn’t,” said Edgar Quero, who recently returned to Tucson to look after his father.

Chaka got beaten up sometimes on the street and punks would steal the few dollars he carried. The beat cops also knew him. Not long ago, Chaka was on the street with a pellet rifle, which prompted calls to the police.

Despite Chaka’s struggles with booze, Edgar accepted his father.

“I don’t care what people would say,” he said. “I loved him for the way he was. I respected him for being my dad.”

There was a time when people talked about Chaka’s abilities and not his drinking. He was talented at reworking a car’s body and painting it with luxurious colors and images. Sleek, chill low-riders were his specialty.

He worked at several car body shops along South 12th and South Sixth avenues. His talent was known far and wide, and car owners and body-shop owners would seek him out, Joel Moreno said.

“He was the best,” Moreno said.

Chaka’s life, nonetheless, was difficult. There was worry that an accident was waiting to happen.

“It was always on the back of my mind,” Edgar said. “I would tell him to be careful.”

Joel Moreno told his friend the same. But he didn’t think Chaka’s life would end on the corner that he called his roost. “When I got the call at 1 in the morning, I didn’t believe it.”

Neither do Chaka’s many other friends, said Marisa Moreno.

“It’s not gonna be the same anymore passing by that corner.”