It was 1965, and in a small classroom, Norah Booth was a sophomore in a social studies class taught by Sister Clare Dunn, who had arrived in Tucson from California that year.

“We were always talking about issues of social justice,” said Booth. The classroom was at Villa Carondelet Academy, a Catholic girls’ middle and high school behind St. Joseph’s Hospital on North Wilmot Road.

Dunn stimulated the students to think about others, to consider the issues of fairness and inequity, Booth said. Dunn, who was 32 years old at the time, told her students to show compassion and to support those who had less.

There were, as in any year, pressing social and political issues.

President Lyndon B. Johnson stepped up troop deployment to Vietnam and U.S. Marines were sent to the Dominican Republic torn by civil war.

In Selma, Alabama, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. led thousands of civil rights protesters, in three separate marches, to demand the end of discriminatory voter-registration rules as local police used violence against the marchers. Hundreds were arrested and at least two protesters were killed. In the summer of that year, widespread riots wracked the Watts section of Los Angeles, leaving more than 30 dead and more than 1,000 injured.

In California, Filipino and Mexican agricultural workers initiated strikes to demand better working conditions and pay, and joined forces to launch a grape boycott, eventually leading to the formation of the United Farm Workers of America under the leadership of César Chávez and Dolores Huerta.

And in Rome, Vatican II, a global ecumenical council led by Pope Paul VI to reform the Roman Catholic church and make it more relevant, opened for the fourth and final period.

Nine years after Dunn began teaching in Tucson, including several years at Salpointe Catholic High School, she took her principles to a wider public. In 1974 she was elected to the state House of Representatives representing midtown’s District 13.

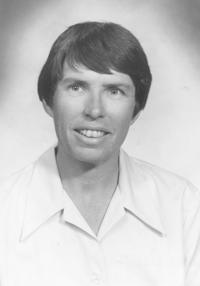

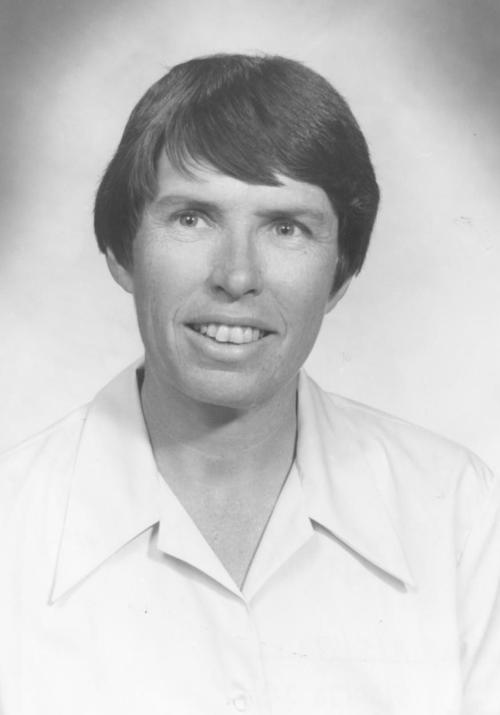

She became the first nun in the United States in the 20th century to enter public office, according to Booth, who is writing a biography on Dunn.

Dunn advocated for legislation to improve the lives and conditions of women, the poor, minorities and others who were marginalized by government. Moreover, as a liberal Democrat in a Republican-dominated state legislature, she maintained her poise and positions with honesty and directness.

On July 30, 1981, Dunn and her legislative aide, Sister Judith Mary Lovchik, died in a two-car collision north of Tucson.

In her short time, however, Dunn made a deep impression on her fellow legislators and the public.

Late last month, Dunn was inducted into the Arizona Women’s Hall of Fame. Booth, a freelance writer who taught writing at Sunnyside High School and Pima Community College, nominated her teacher.

“She did a lot for the state. She did a lot for a lot of people,” Booth said.

In her research, Booth found that Dunn introduced 29 bills and cosponsored or signed on nine Senate bills in her first year in the House. The following year she introduced 107 bills. She would introduce more bills in subsequent years.

Dunn supported increased access for voting, vote by mail and automatic restoration of voting rights to freed prisoners who met sentencing and parole requirements. She worked for women and children’s rights. She wanted the state to pay for textbooks for courses required in high schools and to give tax breaks for working families. She moved legislation to allow the sale of less expensive generic drugs and to exempt veterans from paying the vehicle license tax.

One of her most important bills would have eliminated the sales tax on food groceries, but that wouldn’t become law until after her death. Likewise, her support of making January 15 a legal state holiday in honor of King came to pass years later.

She was passionate about the Equal Rights Amendment. She spoke fervently for the proposed Constitutional amendment throughout her legislative career but it never came to pass.

Bruce Wheeler, who was elected to the House in District 13 the same year as Dunn, said she brought energy, empathy and a much needed sense of humor to the tough legislative process.

“She was a dedicated and empathetic person who wanted to make change,” said Wheeler.

Both Booth and Wheeler said that while Republican legislators disagreed with and opposed Dunn, they respected her convictions and dedication to her positions. They could not afford to ignore her, they said.

“She was the voice of conscience,” Wheeler said.

Had Dunn lived, she would have found today’s political barriers and challenges in state government similar to those she encountered. But there would be one constant, Wheeler said.

“She would be the same today as she was then,” he said. “She was consistent.”