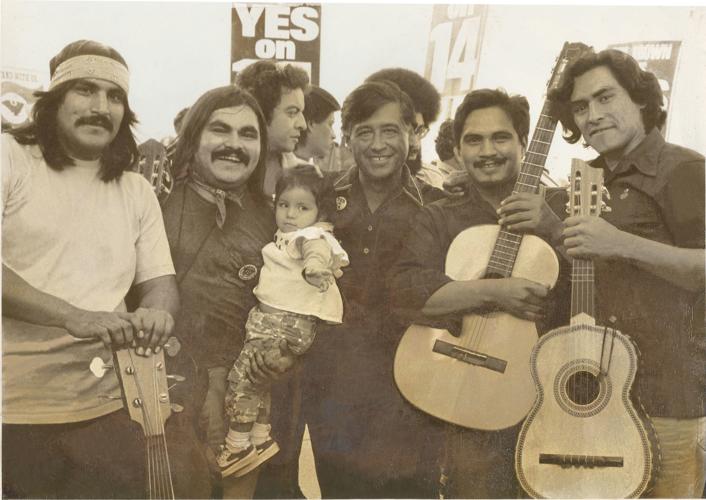

He was considered César Chávez’s favorite musician.

Ramon “Chunky” Sanchez, who was born in a California desert town to a farmworker family and who settled in San Diego, wound up to be one of the leading musical voices in the Chicano rights movement that emerged in the 1970s.

He was an activist. An educator. A mentor to young Chicano and Chicana youths. He was a musical icon who helped build on the foundation of Chicano-roots music. He was the recipient of one of our country’s top arts awards.

While Chunky Sanchez, who died in October 2016, lived and worked in a different time zone than ours in Tucson, his influence spread beyond the Pacific Coast. Now a new documentary about his life and contributions has been made and will be screened in Tucson.

“Singing Our Way to Freedom,” a film by award-winning documentary filmmaker Paul Espinosa, will screen at the University of Arizona’s Gallagher Theatre in the Student Union on Wednesday, Feb. 27, at 6 p.m., followed by a Q&A session with Espinosa.

It was important to document and tell Chunky’s story, said Espinosa in a recent telephone interview from his San Diego home. Sanchez’s role in the Chicano civil rights movement has been ignored and forgotten, Espinosa added.

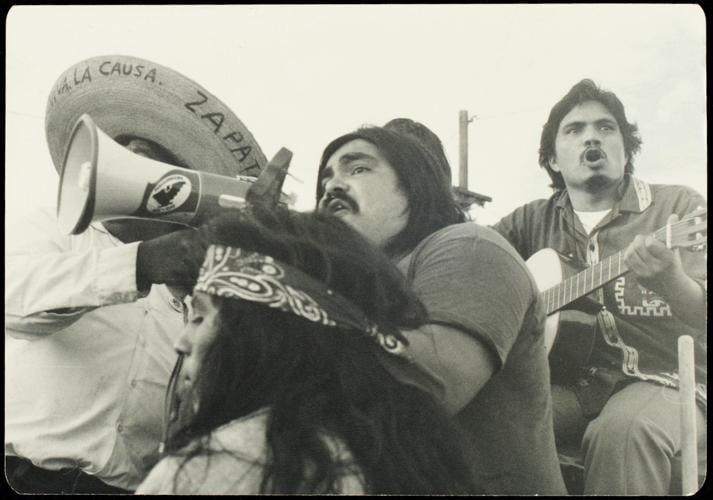

Sanchez was born to a Yaqui family in the desert town of Blythe, California, just east of the state line along Interstate 10. He moved to San Diego and in the early 1970s joined a musical ensemble, La Rondalla Amerinda de Aztlán, which devoted itself to Mexican roots music. About the same time, he joined Chavez and the United Farm Workers, who were seeking improved working conditions and wages for workers in the fields.

“Chunky came from a farmworker background,” Espinosa said. “He understood the issues and understood the importance of music in promoting social justice.”

Michelle Téllez, an assistant professor in Mexican American Studies at the UA, said that there are several lenses through which to view Sanchez’s activism.

Sanchez, who often used the line “let’s educate, not incarcerate,” brought attention to a prison and penal system that was used unequally against Chicanos. He fought against student tracking, which typically meant that Chicano students were guided away from academic programs and into technical training. Sanchez spoke out against injustice and anti-immigrant legislation, and was effective in organizing neighborhoods, said Téllez, who grew up in the San Diego area and personally knew Sanchez.

He used his culture and music as “a way of speaking back and building community,” Téllez added. For years, Sanchez worked in gang prevention and youth education programs in San Diego’s barrios.

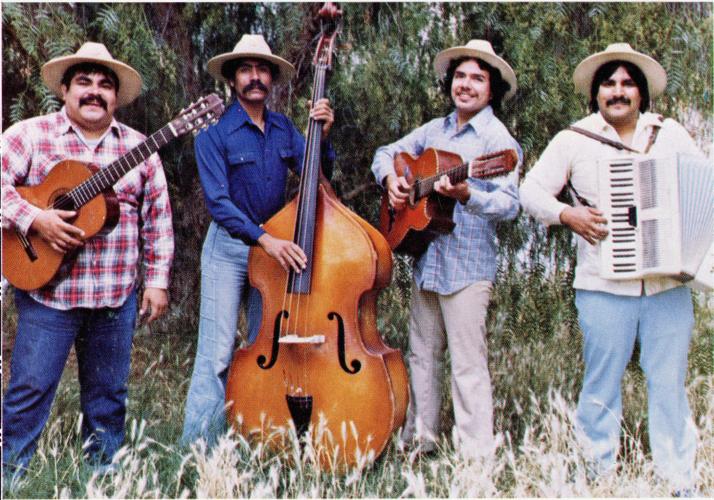

Espinosa said Sanchez spent time in Mexico City to study music, history and culture and upon his return to San Diego, he formed the musical group Los Alacranes Mojados with his brother Ricardo. In the mid-’70s, the group recorded “Rolas de Aztlán,” a record that became part of the soundtrack for the Chicano rights movement. The group’s name in Spanish, the Wetback Scorpions, is a play on words, meant to mock the denigrating word used against Mexicans.

Sanchez began to expand his message by emphasizing that the border was not a barrier to building alliances or sharing culture. “We can cross borders, transcend borders,” Espinosa said.

The group’s songs are a litany of calls for equality and justice and community building: “Yo Soy Chicano,” “Corrido de César Chávez,” “Corrido del Bracero,” “Vietnam Veterano,” and “Chicano Park Samba,” a song that cites the struggle of the Chicano barrio Logan Heights to create a park under the Coronado Bridge.

While he used his music to emphasize political and social activism, Sanchez influenced other musicians, like Los Lobos from Los Angeles, which often played with Los Alacranes.

“His activism and music cannot be separated. He saw music as a tool for doing his activism in the broader social justice movement,” said Espinosa.

Adolfo Guzman-Lopez, a reporter for Southern California Public Radio, credits Sanchez for his political awakening.

“I grew up in Tijuana and San Diego in the late ’70s and ’80s crossing the border almost weekly. My Mexican and American identities were shaped by these crossings but it wasn’t until I heard and met Chunky Sanchez and other Chicano artists as a Chicano student activist, and later through the Centro Cultural de la Raza, that I understood that what I was living was a hybrid life,” he wrote me.

Any appearance that you were adopting “American” culture meant that you were a sellout to Mexico, but when he met Sanchez and heard his music, “that took the best of Mexican and American musical styles to make us recognize and be proud of being in this third space, Mexican, American, and Mexican American,” Guzman-Lopez added.