In April 2006, longtime labor and civil rights activist Dolores Huerta spoke to students at Tucson Magnet High School. In her speech, Huerta, who had more than 50 years of political organizing experience, said that “Republicans hate Latinos.”

A firestorm erupted. Outraged Republican state legislators and national radio talking heads took umbrage. It was as if Huerta had taken a knee during the national anthem.

A year later, Republican legislators set their sights on the Tucson Unified School District’s Mexican American Studies program. And by 2010, the GOP-led Legislature and the governor banned the program — the same year that Arizona Republicans approved SB 1070, a law that enabled local police to stop and detain people on suspicions that they were living here without documentation, which resulted in the racial profiling of Latinos.

Eventually, federal court rulings all but gutted SB 1070 and in August a federal judge ruled that the ban on Mexican American Studies violated students’ constitutional rights “because both enactment and enforcement were motivated by racial animus.”

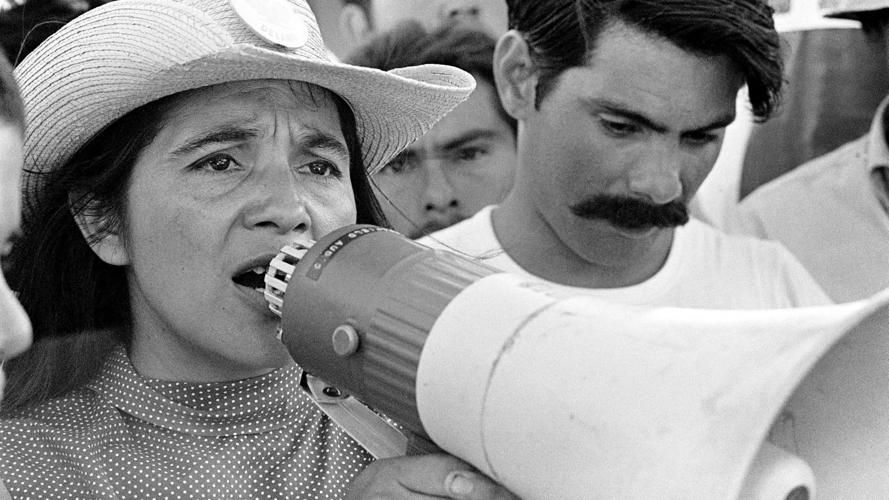

Huerta, who in the early 1960s co-founded the United Farm Workers Union alongside César E. Chávez, has long been on the national stage. Now a new documentary film focusing on her work and life will bring even more attention to Huerta who, often shunted aside in the history books, has been a leading voice in support of agricultural workers, women, the environment and Latino communities.

Huerta, 87, will return to Tucson Oct. 9 to appear at The Loft Cinema, 3233 E. Speedway, for the 7:30 p.m. screening of “Dolores.” She will participate in a Q&A after the film, which opens Oct. 6.

The film, she said, is “historical and relevant to today’s politics.”

Last week I interviewed Huerta, who was at the office of the Dolores Huerta Foundation in Bakersfield, California, by phone for an interview that will air on KXCI-FM.

When I asked her if she felt that her 2006 remark was vindicated by U.S. District Judge A. Wallace Tashima when he ruled that racism was at the basis of the Mexican American Studies ban, Huerta demurred. She didn’t gloat. She simply said, “I’m so happy to hear that happened.”

She easily could have said “yes.”

Instead, Huerta talked about the value and importance of the now-defunct Mexican American Studies program. The program improved students’ overall academics and character, taught them necessary critical-thinking skills and was never compulsory. These were critical points that opponents never acknowledged, that instead were buried by the dog-whistle racial politics of Republicans, led by former Arizona Superintendent of Public Instruction John Huppenthal and former Attorney General Tom Horne, who as Huppenthal’s predecessor launched the campaign to burn and bury Mexican American Studies.

While the Tucson Unified School District canceled the program under state threat of losing millions of dollars in school aid, Huerta is not giving up that the program will return. Moreover, she said all public schools should incorporate ethnic studies into classrooms, from kindergarten to the 12th grade, so students can learn about the contributions of people of color.

“If we don’t include that into our schoolbooks, that means that the racism and the bigotry will continue and our children of color will never be given the dignity that they deserve,” Huerta said. “They will always feel like second-class citizens.”

Since she was a child growing up in the agricultural fields surrounding Stockton, California, Huerta understood clearly that being a worker, being a Latina, relegated her to second-class status. Several years before she met Chávez in the mid-1950s, Huerta had begun organizing farm workers to seek better wages and working conditions. In 1962, Huerta and Chávez formed the National Farm Workers Association, the forerunner to the United Farm Workers Union.

In subsequent years, the UFW took on the powerful growers in California and the Southwest who were aligned with their Republican patrons, former governors Ronald Reagan in California and Jack Williams in Arizona, and President Richard Nixon and the Teamsters Union. In doing so, Huerta and Chávez, and the UFW and its supporters, brought the much needed spotlight on the field workers’ deplorable working conditions. Their efforts also paralleled the burgeoning Chicano-rights movement of the 1960s and 1970s in the urban barrios throughout the Southwest.

Huerta was there. She helped lead. She voiced the dreams and demands.

This may all be history to many, but the issues of the past remain largely the same today, said Huerta. Today’s political climate expressed by President Trump and his administration’s policies on gender and minority rights, immigration and the environment, she said, are “a call to action.”