Miguel and Veronica Soto are close siblings. Miguel is older but they’re not far apart in age. They’re fun and funny together. They are so connected, they can finish each other’s sentences.

Veronica and Miguel share common interests and, as siblings are wont to do, they disagree from time to time. Even argue a bit.

But there is one passion they share deeply: raising awareness about HIV/AIDS and more specifically within the Latino community.

“This is my community and this is what I do for my community,” said Miguel, HIV program coordinator at the Pima County Health Department.

Yup, agreed Veronica. They love their town and its people, and the Soto siblings want people to understand that Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome remains a problem that requires continued attention from policymakers to nanas and tatas in the barrio.

“We’ve never shied away from anything,” Veronica said.

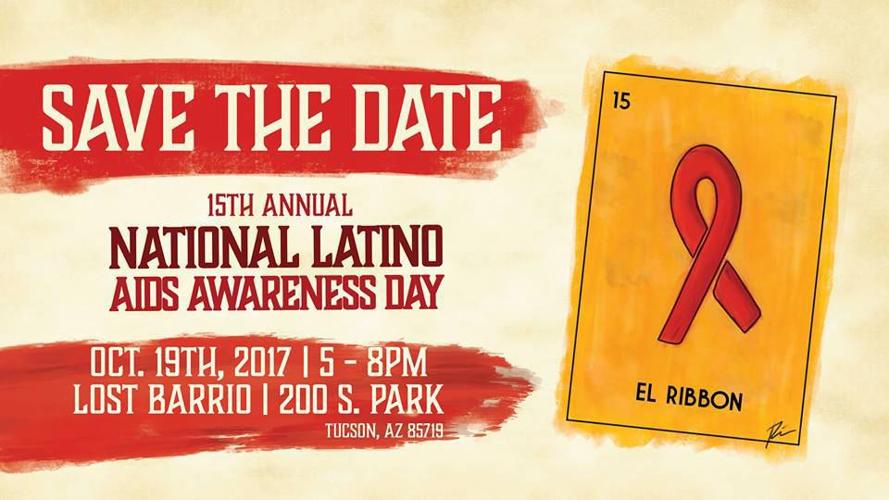

For the pair, and the other individuals and groups who share the same commitment, spreading the word is a year-round endeavor. But among those 365 days, one has stood out for the last 15 years: National Latino AIDS Awareness Day, or NLAAD for short.

This year’s NLAAD is Oct. 19. An evening event has been planned by a committee of which the Sotos are co-chairs for the second consecutive year. The event will be a free, three-hour block party beginning at 5 p.m. on South Park Avenue in Lost Barrio, which old-timers know as Barrio San Antonio.

There’ll be food trucks, aguas frescas and entertainment, but more critically, there will be available lots of information about HIV/AIDS and how the Latino community can deal with it up front and openly.

NLAAD and everything that it represents is a huge task. But Veronica and Miguel seem at ease with their commitment. It’s made easier by their special relationship.

“It’s even stronger than a brother-sister relationship,” said their mother Teresa A. Soto. “I sometimes think they’re like twins.”

Teresa Soto, who worked for 29 years as a teacher’s assistant, at least 21 of those years at Drachman Montessori K-8 Magnet School, said her children have a unique connection and are devoted to their cause.

“He passed on his passion to her,” said Teresa Soto. “She understood what he was working toward and she ran with it.”

While the general population has seen a drop in HIV/AIDS cases, Miguel said the infection rate continues to climb among Latino and African-American males and young people. The principal entryways are shared drug-use needles and having unprotected sex, Veronica added.

Among people who have HIV, one in four do not know they are positive, said Miguel, who has worked for the county health department for 10 years.

Blame the rise on the “super-hero complex” in which some people believe they’re invincible and beyond AIDS’ long reach, and the lame sex education young people receive, if they get it at all.

“We can’t talk about sex education,” said Veronica, who works for COPE Community Services. The moral guardians who make the rules insist that parents instruct their children. “Your sexual health is just as important. But families don’t talk about it,” she said.

The Soto-Rodriguez family does talk about it. It helps that there are a number of educators in the large Soto clan. It also helps that the elders are part of the discussion.

“My nana and tata are so accepting about everything,” Veronica said. “They don’t bat an eye.”

And that openness extends to a younger generation. Veronica said she has consistently been honest and direct about sexual health with her son. So much so she calls him the “condom kid” because he dispenses condoms among his friends or at health fairs, working with his mother.

That’s the goal of NLAAD. Openness. Clarity. Judgment-free.

The move to focus on Latinos and AIDS came when Miguel was working for the Southern Arizona AIDS Foundation. That organization and others were feverishly working on AIDS prevention and awareness among gay men. Later when he moved to COPE, Miguel and others began to direct some of the health programs toward the Latino community. Education programs aimed at the general population failed to take into account cultural differences, nuances and challenges within Latino families. AIDS activists tailored their message.

“It was time to say and do something,” said Miguel.

That time isn’t up, however. So the two will continue speaking up, speaking out and speaking truth to power.