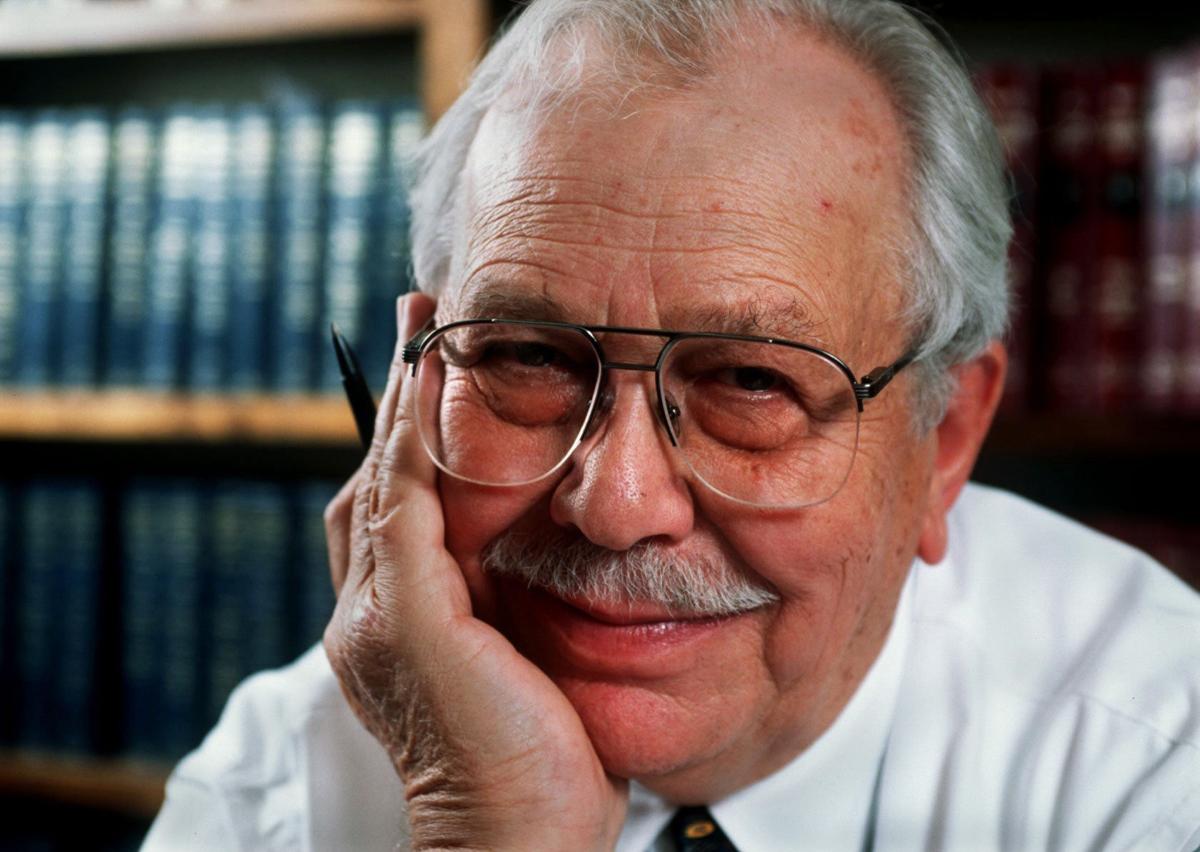

One of Tucson’s most celebrated civil-rights lawyers has died at 94.

W. Edward Morgan, who fought against capital punishment and racial discrimination and took cases other attorneys turned away, died Wednesday after a storied career that spanned six decades and took him all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

“He was someone who couldn’t stand to see injustice,” his wife, Barbara Elfbrandt, said of her husband, who was known for representing people at little or no cost if they couldn’t afford to pay.

Morgan practiced law from 1945 until 2006, when a stroke forced him to retire. He had been in failing health in recent years, his wife said.

Morgan’s quest for a law degree got off to a bumpy start at the University of Arizona, she said.

He was nearly kicked out for trying to organize an interracial dormitory off-campus in the 1940s, a time when black students were banned from campus housing.

He went on to win a lifetime achievement award from the UA law school in 2015 — 60 years after he graduated.

UA law school Dean Marc Miller called Morgan “the embodiment of a lawyer committed to public service.”

“He defined his life as a lawyer not by what he did for pay but by the cases and causes he took up for others as a matter of principle,” Miller said in a statement Friday.

“He pursued a life in the law with passion, skill and humor — and leaves a great legacy for future lawyers.”

Morgan’s UA award was one in a long list of honors bestowed by organizations including the National Lawyers Guild, the Arizona Civil Liberties Union and the Arizona Center for Law in the Public Interest.

A celebration of Morgan’s life is set for the Saturday of Thanksgiving weekend. It will take place at the UA law school at 1201 E. Speedway on Nov. 25 from 2 p.m. to 4 p.m.

The seeds of Morgan’s activism were sown early in life.

Born in 1923 in New York City, he spent much of his childhood in hospitals due to painful orthopedic problems and developed a lifelong love affair with books, his wife said.

He arrived in Tucson in 1935 at the age of 12, still wearing leg braces. Morgan told the Arizona Daily Star in a 1996 interview that he was appalled by the extent of racism he saw here.

He recalled how school officials tried to stop him from attending Safford Middle School — across the street from where he lived — because they said it was a “Mexican” school.

Instead, he was told to go to Mansfeld, an “Anglo” middle school in a white neighborhood several miles away.

Morgan insisted on going to Safford and said it opened his eyes to what people of color encountered.

“I was exposed to viewing the community from the view of a minority culture toward the dominant culture.”

The social upheaval of the mid-20th century figured prominently in his life and career.

In the 1950s, he represented the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People during the integration of Tucson’s public school system.

In 1964 he traveled twice to Mississippi to take part in a campaign dubbed Freedom Summer, a volunteer effort to register black voters.

He was best known professionally for two U.S. Supreme Court victories in 1966.

In one, the high court struck down an Arizona law that required school teachers to take a loyalty oath stating they were not communists and had never supported leftist organizations.

Elfbrandt, the plaintiff in that case, later became a lawyer herself and went on to wed Morgan 30-plus years later after both were widowed.

Morgan’s other high court win resulted in a murder conviction being overturned for a defendant who hadn’t received a hearing on whether he was competent to stand trial.

Morgan was a fierce opponent of capital punishment and at one point in the 1960s represented all 14 of the Arizona inmates on death row at the time, his wife said.

“He lost two cases where his clients were executed and he never forgave himself for that,” Elfbrandt said.

Though he built his reputation on high-profile cases, Morgan has said the high point of his career was his stint as a city-appointed magistrate in the 1970s.

It was “the best job I ever had because you get to do justice every day for the little people, the workaday people,” he told the Tucson Citizen in 2000.

Morgan was active for years at St. Michael and All Angels Episcopal Church until he learned late in life that he was Jewish, something his mother, perhaps fearing religious prejudice, had hidden from him, Elfbrandt said.

He began studying Judaism and was bar mitzvahed at Temple Emanu-El at the age of 84.

Janet Marcotte, retired executive director of YWCA Tucson, said Morgan was the sort of person you could meet once and never forget.

Their paths crossed 40 years ago during a panel discussion on children, and she came away impressed by “his intellect and goodness,” Marcotte said Friday in a Facebook post sharing news of his death.

“I can’t think of anyone in public life I have admired more,” she said.

Morgan is predeceased by his first wife, Eve Kessinger Morgan. He also is survived by four children: Aaron Morgan and Bruce Morgan of Tucson, Katharine Morgan of Callahan, Florida, and Paul Morgan of Kuna, Idaho.