Seven nuns walked through scorching desert from San Diego to Tucson to begin a ministry 150 years ago.

Their feet bled from blisters formed in their black shoes with thick wide heels.

Their legs bled from cacti thorns that pierced through their thick stockings under their long, black habits.

A horse-drawn covered wagon carried supplies and their sparse belongings. The wagon provided shade when they slept under it during the day. They walked by night.

So the stories go, said Sister Irma Odabashian, recalling the history of her predecessors as told in a diary written by Sister Monica Corrigan.

Corrigan detailed the nuns’ trek, which started in Carondelet, Missouri, and went to San Francisco and San Diego before concluding in Tucson — a journey that included travel by carriage, train and ocean steamer, to start their order’s province here in 1870.

The faith, guts, strength and determination of these women is behind the subsequent work of more than 700 nuns of the order of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet, who were sent to Tucson to carry on ministries over the decades.

“God was walking with us in this ministry,” said Odabashian.

A celebration paying tribute to the 150th anniversary of the nuns’ May 26 arrival in Tucson has been postponed because of the pandemic, she said.

The event is now scheduled for next year at the downtown St. Augustine Cathedral, and it will include the unveiling of sculptures honoring the seven nuns and the religious congregation.

Predecessors buried at Holy Hope

Odabashian is among five Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet who remain in Tucson continuing religious work, including some of the 64 ministries the order has carried out in the state over the years.

The women gathered recently at the graves of their predecessors at Holy Hope Cemetery to pray and contemplate their work.

Five of the seven original nuns who settled in Tucson in 1870 are buried at the Catholic cemetery. More than 140 Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet assigned to minister here and throughout Arizona are also buried there.

The order’s members originally were called to serve as teachers in Arizona by Bishop Jean Baptiste Salpointe, who was appointed vicar apostolic of Arizona in 1868.

The seven pioneer sisters in Tucson. Standing from left, Sister Emerentia Bonnefoy, Sister Euphrasia Suchet, Sister Monica Corrigan and Sister Hyacinthe Blanc. Seated from left, Sister Ambrosia Arnichaud, Sister Martha Peters and Sister Maxime Croissat.

So, when the missionary nuns’ province leaders in Carondelet, Missouri, sent them to Tucson, the women opened their first school in the West — St. Joseph’s Academy — in an adobe building next to what is now St. Augustine Cathedral, said Odabashian.

In time, they became administrators and educators at 14 schools, including at Mission San Xavier del Bac, St. John’s Indian Mission at Komatke in the Gila River Indian Community, and parochial schools in Tucson, Florence and Yuma.

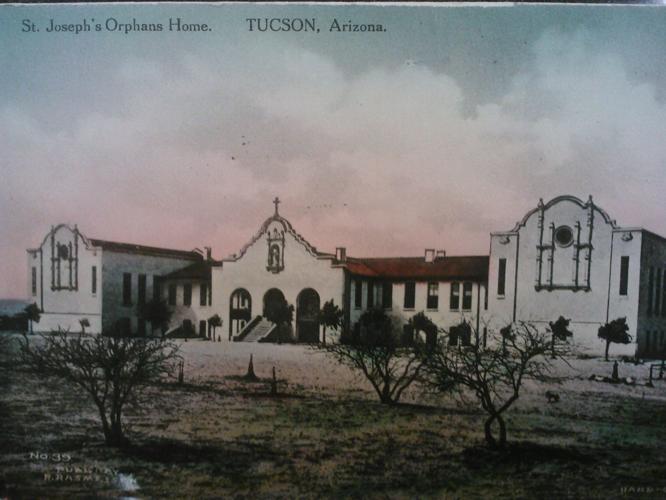

They ran St. Joseph’s Children’s Home, an orphanage that once stood on South 12th Avenue, south of West Silverlake Road.

Nuns also staffed a small St. Mary’s Hospital in 1880 at the request of Salpointe, said Odabashian. She said the hospital was desperately needed to care for injured railroad workers and miners, receiving 11 patients after the 12-bed hospital opened its doors.

The religious women also opened a nursing school at the hospital decades later, and also treated tuberculosis patients. The order’s work spread, including caring for the sick and to educate youngsters in Prescott, too.

St. Mary’s Hospital around 1900. The hospital continues to operate on Tucson’s west side.

Odabashian came to Tucson in 1978 to work as a laboratory medical technologist analyzing blood samples at St. Mary’s Hospital.

She then enrolled at the University of Notre Dame and received a master’s degree in hospital administration, returning to St. Mary’s as an assistant administrator under Sister St. Joan Willert, then president and chief executive officer of St. Mary’s and St. Joseph’s hospitals.

“The most challenging work in administration at St. Mary’s Hospital was being able to reach out to the poor and the underserved as government cutbacks and changes in health care were occurring,” said Odabashian. “We had to deal with charity, care and the ability to make ends meet.”

“God helped us and showed us the way. Our faith energized us,” said Odabashian, mentioning her gratitude to the foundation and the community’s support through private donations and fundraisers.

Willert became board chair of the Carondelet Health Care Corp., overseeing 14 hospitals in the nation sponsored by the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet.

Willert’s vision led to Carondelet Health Network, which today in Tucson includes St. Mary’s and St. Joseph’s hospitals, the Neurological Institute and the Heart and Vascular Institute.

Holy Cross Hospital in Nogales is also part of the network. Now, the parent group for Carondelet Health Network is the for-profit Tenet Healthcare.

Odabashian also worked as a certified interfaith chaplain at St. Mary’s emergency room and the hospital’s mental-health and cancer wards before becoming a patient advocate, retiring in 2018. She continues to volunteer at the hospital and also works with migrants at a short-term shelter.

She recalled other prominent nuns of the order — Sister Kathleen Clark, founder in 1973 of Casa de los Niños for neglected and abused children; Sister Clare Dunn, an Arizona state representative from 1975 to 1981 who was committed to social justice; and Sister Judy Lovchik, Dunn’s legislative aide. Dunn and Lovchik were killed in a car crash in 1981.

Sister Kathleen Clark founded Casa de Los Niños for neglected and abused children in 1973.

Other nuns who live in Tucson are Sister Marge Foppe, who worked as a radiology technologist and in pastoral ministry at St. Joseph’s Hospital; Sister Michelle Humke, who was director of behavioral health and a licensed family and marriage counselor at St. Elizabeth of Hungary Clinic and also trained University of Arizona students in counseling; Dorothy Ann Lesher, who is in pastoral ministry at the Villa Maria Care Center; and Noelle O’Shea, who is in parish ministry at St. Rita in the Desert Church in Vail.

O’Shea, a veteran elementary teacher and high school and college campus minister, came to Tucson in 2000 to oversee children in the pediatric clinic’s waiting room at St. Elizabeth of Hungary Clinic.

Up to 30 children showed up for clinics and waited in a room built to hold 10 children.

“I set up a one-room schoolhouse and I would read to the children in English and Spanish. The older children were my assistants, and I had two aides,” she recalled.

The children also did activities outdoors on a playground, and O’Shea dressed up as a clown during the holidays and for staff picnics. A favorite pastime was when she pulled out her brushes and did face painting.

After five years, she became the liturgy coordinator for St. Joseph’s Catholic Church, and also helped teachers at the school with students reading scriptures during Mass and acting out the Gospel in mime.

For the past nine years, O’Shea has worked at St. Rita’s in religious education, including teaching adults who want to become Catholics.

Now, with the pandemic, her work and that of her fellow nuns is on hold.

“I believe things will get better,” said O’Shea. “I pray to God that he help the scientists find a vaccine and that he help the medical teams treat the sick.”

Some of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet with their students at Mission San Xavier del Bac south of Tucson.

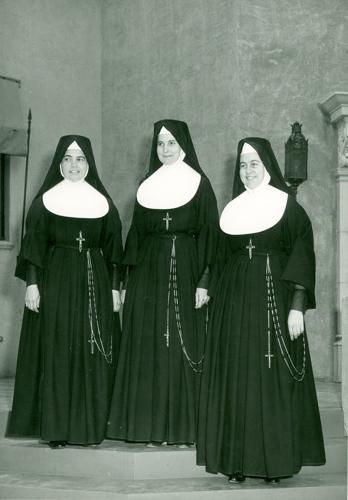

Three of the many Sisters who taught at Salpointe High School