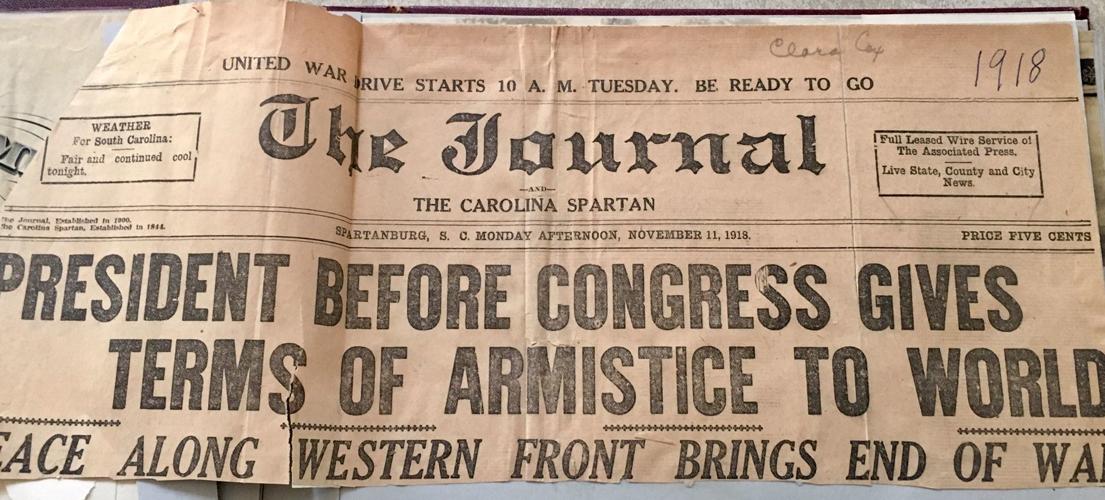

One-hundred years ago on Nov. 11, a young woman from East Tennessee, attending college in South Carolina, clipped out the banner news article from The Journal in Spartanburg.

“President Before Congress Gives Terms of Armistice To World; Peace Along Western Front Brings End of War,” the long-awaited headline trumpeted.

Clara Cox, a concert pianist and editor of her college newspaper, glued the clipping into a scrapbook.

The news surely meant that her fiancé, 2nd Lt. Sam Coile, would be coming home from the World War — to finish the architecture schooling he interrupted to join up and to take care of some unfinished planning for a wedding.

They had met when he, the gangly, serious son of a Presbyterian minister in Knoxville, had knocked at the door of her parents’ home as he sold Bibles to help pay for his university studies.

He couldn’t believe his lucky stars when she, a dark-haired beauty with soulful eyes and charming wit, the daughter of a prosperous telephone-company pioneer, opened the door.

Now, she pasted the Armistice Day article near grainy photos of a 6-foot-4-inch, uniformed man in European locales, and other mementos of Sam’s service. Among them was a brittle, unopened stick of gum. It had been in a care package she mailed to him, but it traveled waywardly around the world before finally getting to him, he explained, bemused, when he sent the gum back to her in a letter to complete its journey.

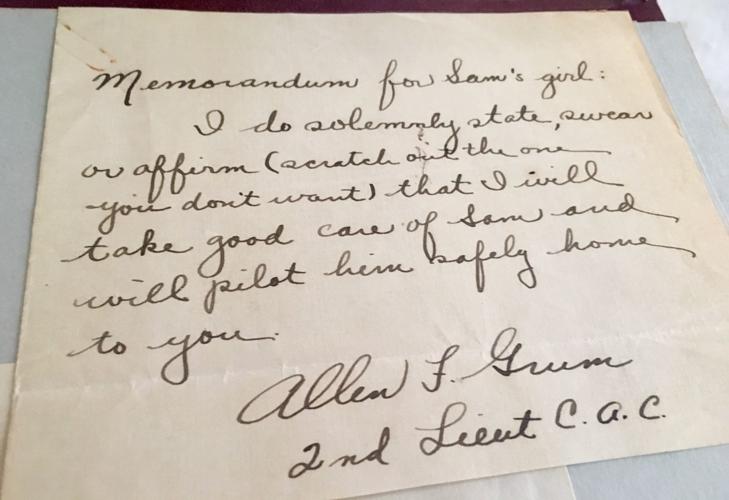

There was also a “Memorandum for Sam’s girl” written for her during the frightening wartime year of 1917. “I do solemnly state, swear or affirm that I will take good care of Sam and will pilot him safely home to you,” wrote Allen F. Grumm, 2nd lieutenant, Coastal Artillery Corps.

Sam finally received notice on May 12, 1919, that he would be shipped from Brest, France, to the United States aboard the S.S. Imperator.

He had completed 12 months with the Coast Artillery Corps in the American Expeditionary Forces on the brutal Western Front and was authorized to wear two service chevrons.

A few weeks later, Clara received a letter penned in flowing cursive by her fiancé’s dear friend and fellow serviceman:

“Sam’s girl, Having brought Sam back to you from overseas, and finding it impossible to keep a watchful eye on him since he doffed his military uniform, I respectfully request that I be relieved of further responsibility. Signed, Allen F. Grumm, 1st Lt., CAC”

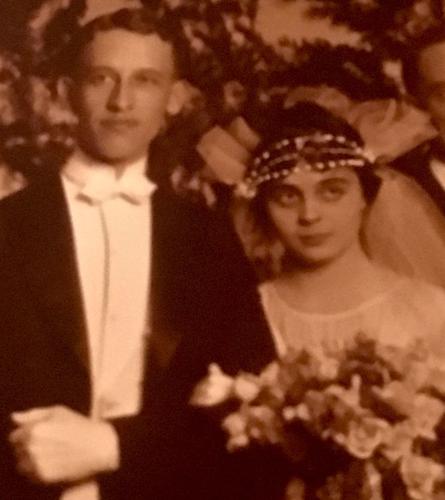

That letter, too, found its home in her scrapbook, a few pages before she would close out the year by adding the photos of her wedding in her parents’ home in Cookeville, Tennessee, on New Year’s Eve 1919.

Sam was home safe, their lives together were beginning, the Twenties were roaring in and Clara wore an early flapper-style headband on her veil. The Great Depression — which would cost Sam his beloved and by-then-prominent career as a architect — was a decade away. By then, their children, Martha and Jack, would be born, their destinies to be shaped by the economic crash and by their own calls to service in World War II.

Sam would go on to a second career, with the help of his father-in-law’s friendship with FDR’s secretary of state, Cordell Hull, a fellow Tennessean. Landing in Washington, D.C., Sam helped to write and then oversaw implementation of the society-changing G.I. Bill for the Veterans Administration. He paid off his final Depression-era debt in the early 1960s. He and Clara lived to celebrate their 50th wedding anniversary together.

All would be documented in the heaps of fragile, yellowing scrapbooks that two of their grandchildren and one of their great-grandchildren would find in old family boxes in 2018, a century after that Armistice Day, now observed annually as Veterans Day.

It’s a perfect time to say, in their memory, “Thank you for your service.”