The outside contractors conducting the Senate’s audit of the 2020 election told GOP lawmakers Thursday they already identified a series of inconsistencies between information Maricopa County reported and what they’ve found.

The result could be workers from Cyber Ninjas showing up at the doors of some voters to try to resolve the claimed disparities — although Maricopa County election officials denied several of the contractors’ allegations.

Senate President Karen Fann confirmed that she is considering giving the go-ahead to visit voters’ homes, despite being told earlier this year by the U.S. Justice Department it “raises concerns regarding potential intimidation of voters.’’

Fann also is weighing new subpoenas to force Maricopa County to turn over information that the outside auditors said they never got or were denied. That would pave the way to a new round of court cases connected to the review of the county’s voting equipment and 2.1 million ballots.

But a judge’s ruling — and the announcement of a congressional committee probe — both mean it might also be Cyber Ninjas, and other firms conducting the audit, that become subject to closer examination.

Public disclosure ordered by judge

Earlier Thursday, Maricopa County Superior Court Judge Michael Kemp rejected claims by Fann that documents in the hands of Cyber Ninjas, including who is financing the review, are not public records and need not be disclosed. Kemp rejected arguments that only documents in the Senate’s actual possession are subject to the state’s public records law.

“Nothing in the statute absolves Senate defendants’ responsibilities to keep and maintain records for authorities supported by public monies by merely retaining a third-party contractor who in turns hires subvendors,’’ Kemp wrote. He noted that Fann herself made statements that the audit is a public function.

Allowing those documents to now be shielded, the judge said, “would be an absurd result and undermine Arizona’s strong public policy in favor of permitting access to records reflecting governmental activity.’’

Significantly, the information the judge said should be released to the public includes who is financing the audit. The $150,000 the Senate agreed to pay Cyber Ninjas “appears to be far short of paying the full cost,’’ Kemp said.

“The public does not know who is financing the remaining costs,’’ the judge wrote.

Kemp was no more impressed by arguments that how the Senate obeys or interprets the public records law is a “political question’’ beyond the reach of courts.

He said it is true that judges cannot tell the Senate how to conduct the audit.

But Kemp said what is at issue here is the enforcement of the public records law, a statute crafted by the Legislature itself. And he noted that lawmakers have not exempted themselves, “which supports the conclusion that the Legislature intended to bind itself to comply with the public records law.’’

“It is difficult to conceive of a case with a more compelling public interest demanding public disclosure and public scrutiny,’’ the judge wrote.

Investigation in US House

Meanwhile, the U.S. House Oversight Committee has launched its own investigation into the audit.

In a letter Wednesday to Cyber Ninjas CEO Doug Logan, Rep. Carolyn Maloney, D-N.Y., who chairs that panel, demanded he produce information about the company and with whom he is communicating, including former President Donald Trump and others who have advanced the theory the election was tainted.

“The committee is seeking to determine whether the privately funded audit conducted by your company in Arizona protects the right to vote or is instead an effort to promote baseless conspiracy theories, undermine confidence in American’s elections, and reverse the result of a free and fair election for partisan gain,’’ Maloney said in a joint statement with Rep. Jamie Raskin, D-Md., who chairs the subcommittee on civil rights and civil liberties.

Contractor cites irregularities

Kemp’s ruling and the results of the hearing Thursday portend months more of legal disputes.

During the hearing, Logan identified a series of what he said are irregularities, explaining them to Fann, R-Prescott, and Sen. Warren Petersen, R-Gilbert, who chairs the Arizona Senate Judiciary Committee.

For example, the Cyber Ninjas CEO said there were 74,243 mail-in ballots received “where there is no clear record of them being sent.”

Logan also said there were 11,326 individuals who did not show up on the version of the voter rolls prepared the day after the election but did show up on the Dec. 4 list as not only being registered but having voted.

And he said there were nearly 4,000 people listed as registering to vote after the cutoff on Oct. 15.

A canvass of voters would be “the one way to know for sure whether some of the data we’re seeing, if it’s real problems or whether it’s clerical errors of some sort,’’ Logan said.

Doug Logan, left, CEO of Cyber Ninjas, tells GOP lawmakers about irregularities he said have been found so far in the review of Maricopa County ballots and equipment. With him is Ken Bennett, who is the Senate's liaison with the audit.

In May, after the idea of contacting voters was first floated, an official in the U.S. Justice Department said the plan could intimidate voters. That would violate the federal Voting Rights Act, said the official, Pamela Karlan, principal deputy assistant attorney general.

Fann dismissed those concerns.

In responding to Karlan, Fann promised that if there is any door-to-door questioning, Cyber Ninjas would not select voters or precincts based on race, ethnicity, sex, party affiliation or “any other legally protected status.”

But what Logan appears to want is far more specific, contacting those whose names showed up, or did not, on conflicting documents, to hear directly from them whether they actually voted.

“Canvassing can help validate that information,’’ he said.

Ballot-counting ‘bubble’ issues

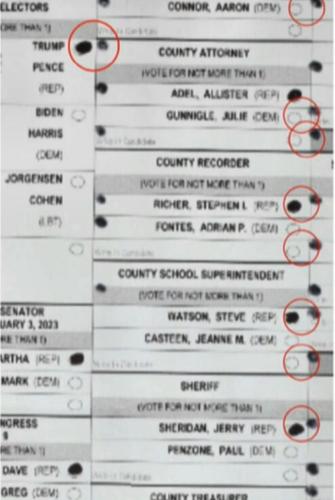

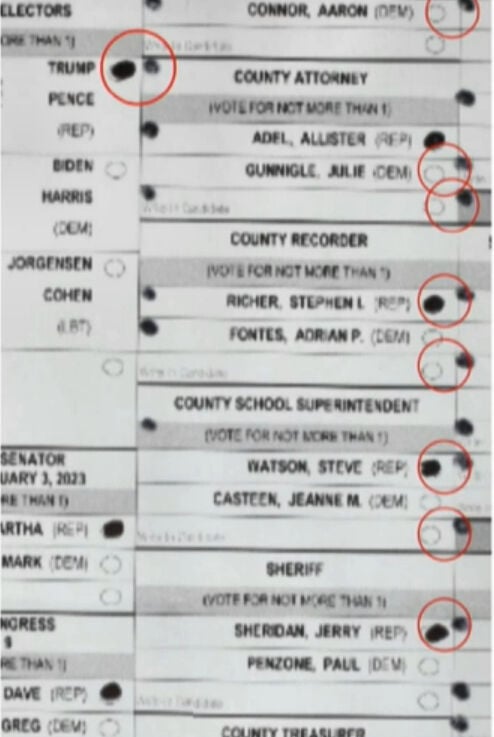

Another big issue is whether the ballots were properly counted.

County officials have insisted that there could be no “bleed-through’’ of marks made by voters on one side of the ballot to another. Even if that did occur, they said the ballots were printed in a way that those stray marks could not affect races on the other side of the sheet because of how the “bubbles” for voters to fill were aligned.

But Logan showed the senators evidence he said shows misalignment of those bubbles as well as actual ballots where stray marks could result either in a vote for someone for whom the person did not intend or could invalidate the choice for that race because it appeared more than one vote had been cast.

He said the problem appears to be confined only to votes cast on Election Day, as the preprinted early ballots were properly aligned. But that still amounts to about 168,000 ballots that were printed and cast at voting centers.

Separately, Logan wants access to images of the signatures on the early-ballot envelopes.

He claimed to have an affidavit — he did not say from whom — that so many early ballots were received, county election workers loosened the standards to determine whether signatures matched what is on file.

Logan said the standards started out at 20 points of comparison but were reduced to 10 and then to five.

“And then, eventually, they were told to just let every single mail-in ballot through,’’ he said. While Logan said it’s too late to redo such comparisons, the images will show whether county officials allowed ballots with no signatures at all to be counted.

Fann said the woman who made the complaint, whose identity she knows, worked to verify signatures for the county. The Senate president said there is no need at this point to reveal her identity.

County hits back on claim

County election officials denied the claim as “categorically false.’’

“At no point during the 2020 election cycle did Maricopa County modify the rigorous signature verification requirements,’’ they said Thursday in a prepared statement.

Ben Cotton, founder of CyFir, a subcontractor on the process, said he found other problems.

Some are related to a breach of the voter registration system the county itself reported, with the FBI having raided a Fountain Hills home days before the election. Cotton said that shows that at least one element of the county’s election system had been “hacked.”

But county election officials said all that was accessed was a site where people could register to vote, not the actual server where voter registration records are stored. All that anyone obtained was someone’s voter registration number, with no access to personal information, they said.

Cotton also said anti-virus software had not been updated since the county acquired the equipment in 2019 from Dominion Voting Systems, nor had there been updates and “patches’’ in the operating system, something Cotton said would be expected even of a home computer.

“What that creates is a tremendous vulnerability to anyone who could get access through a system,’’ he said, especially if the computer server handling voter registration had access into the county’s internal systems.

However, county election officials said they cannot update systems through security patches, saying that would alter a system that had been certified.

“Contrary to Mr. Cotton’s insinuation, the county maintains an air-gapped system and tabulation equipment is not connected to the internet,’’ they said.

A bone of contention between the Senate and Maricopa has been the county’s refusal to provide access to the internal routers, the devices that direct computer traffic. Cotton said such access could help identify who might have breached the system.

County officials have balked, saying the information on the router might compromise law enforcement, including identifying informants. But Cotton said that is at odds with the county’s own assurances that its election equipment operated on a closed system that did not have access to the internet. That means it could not have commingled data with the sheriff’s department, he said.

“The fact that they have responded back to an official subpoena with the justification that to produce that data would compromise these other aspects of the Maricopa County network that does touch the internet is an admission that maybe things aren’t like what they’ve told the American public,’’ he said.

Here's a look into Arizona's post-election audit, where workers are using high-res photography to analyze ballots. Video by Rodolfo Romo.