Rebekah Rucker’s self-contained special education class at Bloom Elementary has a diverse group of kids. There’s a student with Down syndrome, one with a hearing impairment, and a variety of students with different learning and emotional abilities.

A small group gathers around her on the rug as she teaches about social realism.

One boy jumps up and runs to the back of the room to spin a globe. Teacher’s aide Eli Ramirez keeps an eye on him and two other children playing computer games in the corner.

Another aide, Toni Smith, sits near the student with Down syndrome who is engrossed in an educational game on a tablet, singing along with the music in his headphones.

Keeping an eye on the room, Smith sees student Alize Dorame trying to stand and hooks her fingers through the girl’s gait belt, helping her off the floor.

As the lesson comes to a close, one student pulls Rucker aside to talk about something that happened at home.

The teacher listens intently, then tells him he’s loved and safe.

What Rucker and her aides do in the classroom goes beyond education.

Special ed professionals help with health, emotional and behavioral issues, and skills as critical as potty training.

Ideally, Rucker would have three aides. She did at one point in the school year, but there was a shortage in another classroom.

Not enough aides is just one of the outcomes of an underfunded special education system. Across Arizona, there’s a $100 million shortfall in what the state provides for special education students, according to a 2017 analysis by Anabel Aportela, director of research for the Arizona School Boards Association.

A bill introduced by state Sen. Sylvia Allen would go halfway to filling that gap — adding about $50 million for the 100,000 students with emotional disabilities, mild intellectual disabilities, a specific learning disability, a speech or language impairment and other health impairments. Schools currently get $13 above per-pupil spending for those students. Senate bill 1060 would raise that to $500 per student.

The bill passed the state Senate in January and is scheduled to be considered in the House education committee on Monday, March 2.

School district leaders say that the current funding formula does not cover the services for these and other special education students, who often need a host of professionals, including speech and hearing specialists, physical therapists, psychiatrists, one-on-one aides and more.

Pima County’s major school districts, except Vail, say they spent a collective $28.8 million last school year out of their general education fund to cover special education needs, money that would have gone to programs, services and facilities for the entire student body. Vail didn’t respond by the Star’s deadline.

The Tanque Verde Unified School District, with an almost $1 million funding gap, would be able to give their entire staff an 8% raise if those costs were fully funded, according to spokeswoman Claire Place.

Tucson’s largest school district, TUSD, has a K-12 funding gap of $2.2 million, while their gap for preschool services are $3.7 million, according to TUSD Superintendent Gabriel Trujillo. Public schools are required to provide preschool to children with special needs.

While the school districts calculated their funding gaps based on varying expenses, they did not include the cost of transportation, which can be high. The Arizona School Boards Association’s analysis also did not factor in special education transportation costs, which can include door-to-door service for many children.

Marana Unified School District said it has an additional $3.1 million in special ed transportation costs above its $4.4 million funding gap, which both have to come out of the general fund.

STUDENT IMPACT

Tucson-area school district leaders say the special education funding shortfall impacts their ability to pay competitive wages to hire and retain special education professionals, who provide critical services for the consistency and growth of students.

While teacher vacancies are high across the state and nation, there’s an even bigger problem when it comes to special education due to low wages and the high demands of the job.

Some of the highest vacancies are among teacher aides, who can make as little as $12 an hour despite the pressures of the job. Sarah Ledbetter, a special education teacher at Morgan Maxwell K-8 School, often comes home with scratches on her arms and face from a student who had an outburst. Although she has two aides, there are times when she’s alone in a class with 12 kids who have varied and often demanding physical, behavioral and emotional needs.

The two aides spend part of their day going with students into general education classrooms. While those students need a trained professional by their side, teaching them to integrate into gen ed is critical for working toward independence. The younger that children gain these skills, the better the outcomes as they get older.

Jenny Santamaria, a special education aide at Maxwell, makes slightly above minimum wage after six years in the district. The work is exhausting, but she says it makes a difference. If she wasn’t married, living in a dual-income household, she wouldn’t be able to support herself, she says.

Amphitheater Public Schools Superintendent Todd Jaeger says the district is always lacking between 20 to 30 aides, which is roughly a 20% vacancy rate. Amphitheater, which has one of the highest rates of students with special needs in the county, reports having an $11 million special ed funding gap. The district has a school that is entirely for students with special needs.

Vacancies aren’t just among teachers and aides, but across positions that serve the special education population. TUSD has high vacancies among sign language interpreters and psychologists, who can easily make more money working elsewhere.

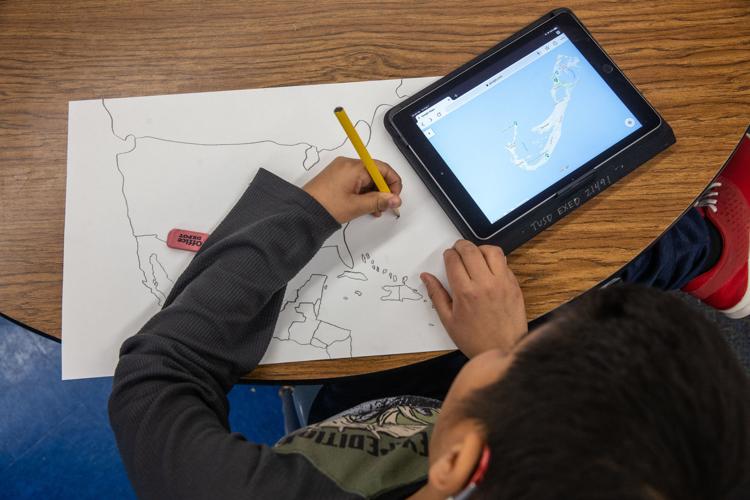

Veronica McCutcheon, a Tucson mom, says the goal for her two children with autism is to be independent. Her 6-year-old son Kaeden started the year at Bloom unable to draw or communicate. With tears in her eyes, McCutcheon took out a drawing he made after months of working with an aide assigned to him. He drew a coin with arms, legs and a little face, and he wrote the word “coins” above it. She says her son’s aide helped him learn to communicate his feelings through pictures. And to her surprise, he was also able to begin spending more time in general education classrooms with the help of his aide.

“You can’t put a price on that, but you want those people to have what they need cause you don’t want them to go away,” she said.

“These people are underpaid and overworked,” she said. “They’re in charge of pretty much raising our children. How can they do their job if they’re not given the tools?”