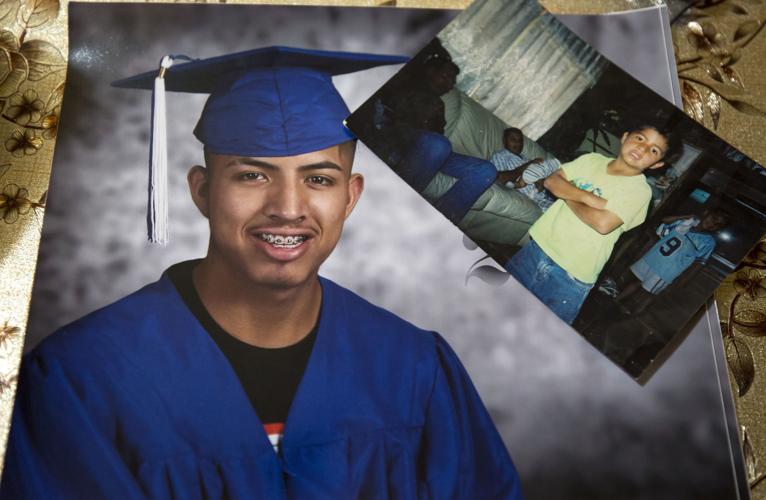

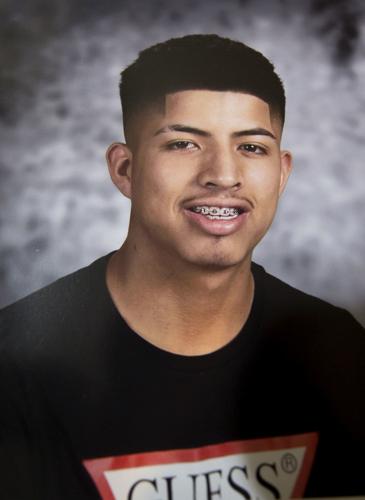

Maria Resendiz Uribe looks at her son’s senior photos taken last year. There is no way Jonathan Torres Resendiz will graduate with his class now.

Instead, the 18-year-old in the photo wearing a blue cap and gown complemented by a big toothy smile is facing deportation to a country he left when was 6 years old.

The Catalina High School student is undocumented, and after being caught on the TUSD campus with marijuana wax and vape pens, he’s spent more than three months in jail.

Uribe crossed the Mexico-U.S. border with her three youngest children in 2008, Torres being the baby. Uribe made the treacherous desert crossing with her kids less than two years after her 45-year-old husband died of hypothermia attempting the same trek.

From Guanajuato, in central Mexico, Uribe says she brought her children here for a better education and a better life.

She says her son’s arrest is the first time he’s ever been in trouble in school or with the law. Neither the Tucson Police or Pima County Sheriff’s departments have a previous record involving Torres.

The teen was caught by school security with a marijuana vape pen on Nov. 4, according to a Tucson police report. Security personnel searched his backpack and found marijuana cartridges and additional wax pens for vaping.

School officials called police first and then his mother. When Uribe got there, Torres was being arrested. Police took out the handcuffs, and she had to leave. It was too painful to watch.

Torres had 11 marijuana cartridges in his possession that day, according to a memo written by Catalina Assistant Principal Michael Beck and provided by Torres’ family. He received a 10-day suspension pending a hearing.

Vaping has become a problem among youth in high schools across the country, with school districts adopting policies to address the matter over the last several years, and the state launching campaigns to raise awareness.

At the hearing, school officials told Uribe and Nasaria Torres, his older sister, that Torres was welcome back at the school. Nasaria recalls school administration telling her mother to be more responsible for her son.

Uribe wishes that rather than calling the police, the school would have just called her.

Tucson Unified won’t comment on specifics in Torres’ case, but the district’s code of conduct mandates calling law enforcement for any allegation of illicit drugs, says Superintendent Gabriel Trujillo.

TUSD was not aware of Torres’ immigration status as that is not information that can be legally tracked.

“It’s a difficult situation,” Trujillo said. “It’s a sad situation. We certainly are very disappointed that this has been the outcome, and our heart goes out to the family.”

A $100 bond was set for Torres’ release the day he was arrested. But when his mom and sister went to pay it, they found out there was an immigration hold on his case.

When a person is booked into the Pima County jail, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement automatically checks their immigration status, says spokeswoman Deputy Marissa Hernandez. If ICE puts out an immigration hold, the Sheriff’s Department will notify ICE before releasing the inmate. The jail tells people paying bond in these situations that ICE will likely take custody of the person before the jail can release them — a process that takes two hours, resulting in the bond that was paid being forfeited.

Torres was sentenced on Feb. 13 for first-time possession charges, receiving 18 months of probation, minimal fines and 200 hours of community service. He has since been placed in an ICE detention center in Eloy.

“JUST A NORMAL KID”

Despite the fact that penalties for possession of marijuana have decreased nationwide, it is still a felony in Arizona.

The County Attorney’s Office regularly files charges against juveniles and adults for minute amounts of marijuana, says Joel Feinman, the Pima County public defender whose office represented Torres on the drug charges and routinely represents defendants in such cases. Spending months in jail during these court proceedings is not uncommon.

Prosecuting people for low-level marijuana charges is “at odds with what we want our community to believe,” Feinman said. Students, ages 16, 17 and 18, are regularly charged as felons, which stays on their record permanently with all the accompanying damage of that label, he says.

Chief Deputy Pima County Attorney Amelia Cramer says Feinman is “twisting the facts.”

Juveniles and adults charged with up to 2 pounds of marijuana possession are usually offered a diversion program, which ends in the charges being dismissed, Cramer said. When diversion isn’t offered, it’s usually because that person has additional, often violent, charges.

Cramer says Torres was offered diversion to avoid a felony charge, which is separate from the deportation case, and does not know why he declined. The family was unaware of such an offer.

Feinman cannot comment on any specific case, but said there are a number of reasons why someone would decline a diversion plea deal.

In the meantime, Torres is awaiting deportation proceedings. While his friends and family would like to hire a lawyer, they’ve yet to find one they can afford.

Volunteer attorneys with Keep Tucson Together, a partner of the county public defender’s office that represents low-income people in immigration court, will take his case if the family can’t obtain a private lawyer.

The volunteer group attempts to get people who are bond-eligible out of custody. Torres’ family hopes the immigration court will issue a bond. But even if it does, those costs vary widely and can run in the thousands, says public defender Margo Cowan, who runs the operation.

Cowan says there are routes to seek relief from deportation in a case like Torres’. One may be seeking asylum from a region he doesn’t know and where he could be at risk.

“When people have been out of their community for a long time, they’re easy targets,” Cowan says. “They stand out.”

Most of Torres’ family is in the U.S., except for one older brother who Torres hasn’t seen in eight years.

Uribe says her son cries to her on the phone. He doesn’t know what he would do in Mexico. She wipes tears away, thinking of her son alone and afraid.

In school, he was studying mechanics and carpentry. He looked forward to his classes, his mother says. And he worked to help pay for his own things and to cover necessities.

As a kid, he helped out in the restaurant where his mom worked. When she had to quit that job because of health problems, Torres quit playing soccer so he could work more.

For the eight or nine years Torres played soccer, he was the first to show up to practice and the last to leave, says Daniel Roth, who coached him for much of that time. Roth’s wife often picked up Torres and brought him along with her own son to practice.

Roth says Torres was a model player and a good kid.

The company Roth works for, M3 Engineering and Technology, sponsors refugee and immigrant children who live below the poverty line, which is how he ended up coaching Torres.

A lot of the kids Roth has dealt with got into trouble at times, but “Jonathan was always clean,” he said.

Most kids vape, Roth says. He thinks what happened to Torres is unacceptable.

“I don’t think he’s really that off track,” he said. “He’s just a normal kid.”