Armed border militias descended on Arivaca a decade ago determined to stop illegal immigration and cross-border drug smuggling, but their zeal led to tragedy.

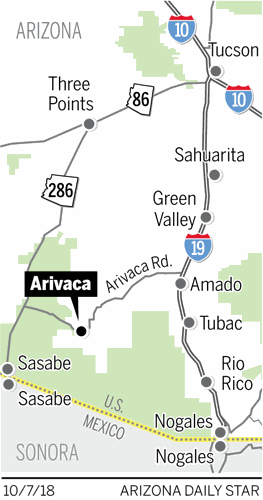

Now, residents of the remote town an hour southwest of Tucson find themselves dealing with an eerily familiar situation.

In late August, a black armored vehicle with a .50-caliber replica machine gun on top rolled into Arivaca. A few days later, a ragtag group spouting military-style rhetoric came to town and started accusing people of sex-trafficking children. Their arrival aggravated an already tense relationship between some Arivacans and a local man who has organized armed patrols south of town since early last year.

The arrival of a BearCat armored vehicle was disquieting for Arivacans, who still remember a 2009 home invasion by men linked to a militia that left two people, including a 9-year-old girl, dead.

After the arrival of the armored vehicle and the wild accusations, on Sept. 9 about 70 Arivacans set up rows of folding chairs on the wood floor of the one-room schoolhouse to figure out what they should do. Sheriff’s deputies couldn’t step in until the newcomers broke laws. In the meantime, the local bar posted a sign saying militia groups weren’t welcome and one resident got Facebook to remove the most inflammatory pages one group posted.

Foremost in their minds was the worry this wave of newcomers could lead to a similar tragedy as the 2009 home invasion orchestrated by members of a group called the Minutemen American Defense militia. The shooting left 9-year-old Brisenia Flores dead alongside her father, Raul Flores, 29, and put two of their killers, Shawna Forde and Jason Bush, on death row.

“I don’t want to live in fear that one of my kids is going to be the next Brisenia,” resident Eli Buchanan said as he stood to speak at the schoolhouse meeting.

Arivaca resident Clara Godfrey called the outsiders “cucarachas” — cockroaches. She knows the chaos they can cause: She said her nephew Albert Gaxiola was coaxed by militia members into taking part in the deadly home invasion. He is now serving two life sentences in an Arizona prison.

She worried that some misguided townspeople might be persuaded to join the new groups and urged residents to shine a light on them so they would “scurry back into their corners.”

Leaning on a cane as he spoke to the crowd at the schoolhouse, Dan Kelly said his fear was that “one of these characters is going to come in to ‘save the children’ and go on a shooting spree.”

Clara Godfrey takes the floor during a meeting of Arivaca residents last month, when about 70 people gathered to discuss militia groups that have settled in the area.

Arivaca is a haven for artists, hunters, retirees, ranchers and families who want to live somewhere quiet and be left alone. The remote town of about 600 residents sits a dozen miles north of the U.S.-Mexico border and straddles cross-border smuggling routes, making it an inviting landing spot for vigilantes and citizen militias from across the country.

Bryan Melchior, co-owner of the Utah Gun Exchange, said he decided to bring his armored BearCat to Arivaca because he saw the town as the “epicenter of what border security is all about.”

He called his BearCat a “provocative marketing tool” for his online gun marketplace and video channel. He vehemently denies being part of a militia. Instead, he described his group as a “bunch of freaking rednecks from Utah that make websites and advocate for freedom and guns and border walls.”

The ragtag group, Veterans on Patrol, came to Arivaca in September after raising a ruckus in Tucson this summer with unfounded claims of child sex-trafficking at a homeless camp. Tucson police found no evidence to support the claim, but tens of thousands of Facebook users ravenously consumed the group’s videos, and many sent donations.

Michael Lewis Arthur Meyer, the group’s 39-year-old leader who is not a veteran, then claimed a skull he found in the desert belonged to a child who was sex-trafficked. The Pima County Medical Examiner’s Office determined the skull belonged to an adult. Meyer’s crusade led him to allegedly break into a home in Tucson, resulting in a felony criminal trespassing charge in Pima County Superior Court. He also has an outstanding warrant for not appearing in court on an unrelated assault charge.

Meyer would not talk with the Arizona Daily Star.

The schoolhouse discussion repeatedly turned to Tim Foley, the founder of Arizona Border Recon, who moved to Arivaca in early 2017 and runs armed patrols near the border.

Foley discounted any notion that he was part of a militia: “Look how many guys I’m surrounded by,” he said sarcastically, sitting by himself in his den. The only one in Arizona Border Recon that has a military rank, he said, is Sgt. Rocco, a pit bull curled up at his feet.

Tim Foley’s Arizona Border Recon group includes about 200 volunteers who search out border crossers.

“Created a mess”

Before coming to Arivaca, Melchior of the Utah Gun Exchange spent the summer traveling the country filming events to promote gun rights. He also held counterprotests of the survivors of the mass shooting at a high school in Parkland, Florida, in February, who he believes have been co-opted by anti-gun activists.

He came to Arivaca to film the border area in anticipation of President Trump’s threat to shut down the government by Sept. 28 if Congress didn’t fund his border wall.

Standing next to a creek that runs across the border, Melchior plugged a memory card into his laptop and started downloading video footage taken by motion-sensor cameras he set up. The footage will be uploaded to the exchange’s online video channel, which Melchior said is a platform for videos that might be excluded from YouTube or Facebook.

Melchior said the Utah Gun Exchange wasn’t associated with Veterans on Patrol. The first time he heard of Meyer was after Melchior got to Arivaca. Melchior reached out to Foley to set up an interview after seeing him in news reports.

“All we did was come down here and start interviewing people and asking questions,” he said with a rueful chuckle. “I’ll tell you, it’s created a mess.”

Bryan Melchior says he came to Arivaca to film the border area in anticipation of President Trump’s threat to shut down the government if Congress didn’t fund his border wall.

In retrospect, he said he should have been “more knowledgeable on the town’s anti-militia sentiment” before he came to Arivaca, adding “the BearCat is a military vehicle, so I get it.”

Still, he said Arivaca was one of the most unwelcoming of the many towns he has visited. Rather than sell him “$20 cocktails” as bars in other towns do to tourists, he was banned from La Gitana Cantina, the local watering hole and community hub.

Propped up against the bottles behind the horseshoe-shaped bar is a paper sign reading “No Militias, Never Again,” a phrase also printed on T-shirts worn by several people at the schoolhouse.

That sign caught Melchior’s eye when he went to get a “burger and beers” a few days after arriving in Arivaca. When he asked about it, the bartender told him it referred to the 2009 fatal home invasion.

The conversation was cordial until he mentioned he had contacted Foley, Melchior said.

“Instantaneously, the whole entire experience changes,” he said.

The bartender made it clear no militias or associates of Foley were welcome in the bar, he said.

The bar posted a sign on the front door making the no-militia policy public. When Melchior went in to ask why, he was told some of the videos posted on the Utah Gun Exchange website, Build The Wall TV, had “raised holy hell in the town” and his group was banned from the bar.

The bartender also objected to the video camera Melchior had strapped to his chest and told him it was illegal for him to bring into the bar the alcoholic lemonade he bought across the street at the Mercantile.

The bar also was a flashpoint when Veterans on Patrol came to town.

They had a drone on the table, which reminded bartender Megan Davern of a rancher who complained days earlier about a militia group trespassing on his land and flying a drone. They told Davern they were in Arivaca to save children from being sold into sex slavery at the border, she said. One of their group told her they sometimes worked with Foley.

Dan Kelly, center, with Ken Buchanan and Megan Davern, says he worries that “one of these characters is going to come in to ‘save the children’ and go on a shooting spree.”

Minutes later, a patron at the bar told her there was a man taking pictures of the humanitarian aid office for border crossers across the street, she said.

“At this point, there’s this real ramping up in the bar of ‘what is going on?’” she said.

She went outside and told them to leave and never come back.

In a video Meyer posted on Facebook, he suggested the humanitarian aid office was part of a nonexistent ring of child sex-traffickers. In other videos, he threatened water tanks in town and said he would build a wall north of Arivaca to cut if off from the United States.

While some residents are concerned, others see no reason to worry. A woman whiling away the afternoon with her friend at a burrito truck near La Gitana said local businesses should cater to anyone who isn’t breaking the law.

Steve Rendon

Steve Rendon, manager of La Siesta Campgrounds where the BearCat is parked, said the 2009 fatal shooting, which happened down the road from the campground, was a “scary thing and it’s very, very sad.”

At the same time, the group of people who dislike Foley are the same ones complaining about Meyer and Melchior, he said.

His main question: Why does Arivaca attract border-security vigilantes when many other towns in Southern Arizona have similar problems with smuggling? Nobody knows for sure, but Foley’s name came up repeatedly as a magnet for vigilantes.

“It will never improve”

Foley founded Arizona Border Recon eight years ago in Sasabe, a small border town southwest of Arivaca, and moved to Arivaca in May 2017. He now lives on a hilly dirt road on the east side of town.

Soon after he arrived, the town held a Memorial Day celebration and made T-shirts that read “No militia Never again,” which Foley said were made with him in mind.

His group includes about 200 volunteers from across the country who set up cameras on smuggling trails and search out border crossers. For a “good op,” he usually has a dozen or so men show up, he said.

Sitting at his desk, Foley scrolled through videos he had taken of illegal border crossers dressed in camouflage trekking through the hills south of Arivaca.

He said he has turned over “hundreds” of people to the Border Patrol and that he had never fired a shot at anyone while patrolling the border.

Foley wasn’t invited to the schoolhouse meeting and scoffed at the idea that another incident like the deadly home invasion could happen soon.

He supported Meyer when he was helping veterans in Tucson, calling the group an “outstanding organization.” But now, Meyer’s efforts were derailed because his “distrust of the government is so big” and he won’t “focus on one thing.”

Before the flare-up in early September, “they forgot who I was,” Foley said of the townspeople who dislike him.

“It’ll simmer down, but it will never improve,” Foley said of his relationship with the town.

Bryan Melchior, with a Beretta pistol on his hip, downloads trail cam footage gathered from the border to his laptop.

“They don’t want to know me. So that’s fine. I don’t want to know them if they’re going to be that ignorant and don’t want to sit down to an open dialogue,” he said.

Foley said his first interaction with Melchior was when Melchior contacted him before coming to Arivaca. Melchior said he planned to spend a few days filming a documentary but ended up staying for weeks.

Although Foley explicitly rejects the idea he is part of a militia, court records show he was intimately involved in militias that formed Operation Mutual Defense to help the Bundy family several years ago during its dispute with the federal government over the use of public land.

A summary of recorded phone calls filed by the FBI in federal court in Phoenix showed Foley talking with supporters of the Bundys about forcibly moving Muslim refugees to Montana. Foley was quick to point out that he resigned from that group.

In a separate incident, the FBI searched his house in 2011 after hearing a report that Foley said he planted explosive devices along smuggling trails near Sasabe. Foley said he never set any booby traps and, after spending hours searching his home, the FBI came away empty-handed.

Les Rivett sports a T-shirt from years before, when the town first had to deal with an influx of militia groups.

How to respond?

At the schoolhouse, the Arivaca residents tried to decide how to respond.

Should they confront the militia members when they see them on the street?

Many residents own firearms and some have military experience, but they worried a confrontation could feed paranoia and spark violence.

Should they ask Facebook to shut down Meyer’s pages, which connect him to the gift-card donations that keep him afloat?

Kelly took the lead on that effort and later said he contacted Facebook and within two days many of the pages run by Veterans on Patrol were taken down. Since then, the group has posted videos, on a new page, from Lukeville and outside the FBI office in Tucson.

What about getting other local business owners to follow La Gitana’s lead and ban the militias?

They said that might be best left to each business owner to decide.

One thing they agreed on was making sure everyone in town knew what was happening. They created a private Facebook page to share information, formed a phone tree in case the situation escalated and started accompanying anyone who felt threatened.

Pima County Sheriff Mark Napier, whose jurisdiction includes much of the Arivaca area, said he understands Veterans on Patrol is “not a welcome influence in the Arivaca area” and he “does not believe that VOP adds in any way to community safety.”

However, Napier said he was not aware of any criminal activity by the group.

“While their presence may be disquieting to some residents, it might not constitute a violation of the law that we can take action on,” he said.

Mountain plateaus and valleys make for a varying landscape south of Arivaca on Sept. 26, 2018.