Editor's note: Author Charles Bowden spent three years as a newspaper reporter in Tucson. Among those who worked alongside him, and learned from him, was Star environmental reporter Tony Davis, who wrote this remembrance.

Charles Bowden wrote with the lyricism of a poet, the outrage of a century-ago muckraker and the foresight of a prophet.

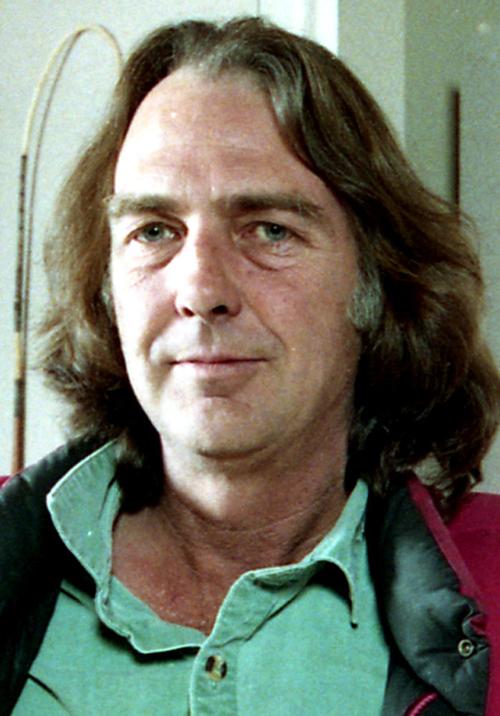

He was tireless, edgy, and at times intimidating and overpowering to sources. At 6-foot-4 and 185 pounds, his physical stature alone was enough to get him an entre to otherwise reluctant interviewees. Yet he was gentle and nurturing with younger writers.

He could grasp the essence of a person or a situation in a matter of minutes, but could stick to a single subject for 15 years.

“He devoured everything passing before his eyes. He had a huge appetite for life, and he had the enormous ability to pour life, death and everything that exists in between, onto paper through his writing,” recalled Julian Cardona, a Mexican photographer who collaborated with Bowden for well over a decade. “He went to any place, there were no limits, and he talked to any person about any topic.”

Bowden, a Tucsonan off and on for more than 50 years, died Aug. 30 at age 69 at his home in Las Cruces, N.M. He had moved there five years ago. The cause of death hasn’t been determined; an autopsy result could be at least a month away, said his sister, Peg Bowden, of Rio Rico.

He left a legacy of 26 non-fiction books and hundreds of newspaper and magazine articles for more than 25 publications ranging from GQ, Esquire and Mother Jones to Arizona Highways, Bicycling and the Teamsters Union magazine.

His topics included the destruction of the Sonoran Desert, child sexual abuse, the murders of thousands in Juarez, the plight of Mexican immigrants, the callous brutality of Mexican drug cartels and the threat to water supplies from overpumping of groundwater.

They revolved around a common theme: how the economic necessities of life create a climate of human desperation that leads to the widespread killing of people and the destruction of nature, said Molly Molloy, a New Mexico State University research librarian who collaborated with Bowden on many projects and lived with him the last five years of his life.

He liked to say that writing, for him, was a gift — just as painting or music was a gift for others — and that to use that gift strictly to make money was a sin.

“This is the news business. You’re supposed to defend the weak and attack the powerful,” he said at a talk in 2010 in Southern California. “Nobody needs court jesters except, I guess, the people in the court.”

He had an absolutely original, distinctive, literary style and choice of subject matter, recalled Tom Zoellner, author of four non-fiction books. He started reading Bowden when "Chuck" wrote for the now-defunct Tucson Citizen while Zoellner attended high school here in the early 1980s.

“He was one of those writers where, within a paragraph of seeing his material, you know you are reading Chuck Bowden.”

Winn Bundy, owner of the Southwestern-oriented Singing Wind Books in Benson for 40 years, called Bowden this region’s best essayist and one of its best writers. “He leads people and he doesn’t push ‘em and bang ‘em. He knew how to write: you have to have a beat. It’s like poetry — if you don’t have a beat, you don’ t have poetry.”

Alan Weisman, a best-selling author on environmental topics, said Bowden at his best was among this country’s top non-fiction writers.

“I don't say that lightly, especially about someone whose entire oeuvre was in first-person, because most first-person writers are either narcissists too in love with the sound of their own voices, or doing it because it's far easier to write in the person in which we live our lives: I,” said Weisman, another former Tucsonan.

THE EARLY YEARS

Bowden never went to journalism school, and he disdained the term journalist. In 2010, he told the Arizona Republic that “I'm a reporter. I go out and report. I don't keep a (expletive) journal. . . . (I) state the truth and give evidence."

He was a history major in college, earning a bachelor’s degree at the University of Arizona and a master’s degree at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and pursuing a Ph.D. from the latter school.

Born on July 20, 1945, he had been raised by Protestant parents in an Irish-Catholic neighborhood on Chicago’s south side, and moved with his family to Tucson in 1957, when he was 11, because of his sister Peg’s asthma.

His father, Jude, an Internal Revenue Service attorney, was well-educated, with passions that included reading Shakespeare and the Bible, Peg recalled. Chuck, too, read widely, taking on the Greek philosophers Socrates and Plato at an early age, and reading classical Russian and French novelists, particularly Dostoyevsky, throughout his life, friends and family said.

He and his sister, at ages 10 and 12, pooled their allowance to buy a monthly collection of classical records — Mozart, Beethoven and Rimsky-Korsakov, Peg recalled. “Then we would turn up the stereo full blast and listen to the symphonies and sonatas,” she said.

Chuck was an early rebel. Attending Tucson High School in the 1960s, he was defiant in the classroom, questioning his teachers’ take on history and literature, and “probably driving them crazy,” Peg said.

“He never toed the line in school. He thought it was boring and stupid,” she said. “He wrote for the student paper, the Cactus Chronicle, and he’d write articles that they wouldn’t publish about civil rights and Vietnam.”

He enjoyed the academic work of graduate school, but after writing his Ph.D. dissertation, he “walked” on his oral defense of the paper and never got his doctorate, she said.

The topic was neurasthenia, or nervous disorders, suffered by smart but bored women in the pre-feminist era of the late 19th century, a topic on which he contributed primary source material to the university library, said his second wife, Kathy Dannreuther, now a retired Tucson public librarian. But he balked when his faculty committee wanted major changes to the dissertation, she said.

“He said the committee was asking stupid questions, and that they obviously haven’t been reading the dissertation,” Peg said. “He felt, ‘Why should I defend a paper they hadn’t read?’ He decided, to hell with it.”

In the mid-‘60s, Bowden ventured to Mississippi to help the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Council efforts to register blacks to vote. He worked directly with the late civil rights activist Fannie Lee Hamer, and at one moment while they sat in her living room, “she called him a white cracker, which highly amused him,” his sister recalled. “I think that was a real taste of social justice for him, front line work with people that mattered, people of color. He was the only white guy with them.”

A WRITER'S LIFE

In 1970, Bowden took an instructor’s job in American history at the University of Illinois’ Chicago campus. He walked out on his contract and moved back to Tucson a year later, he told an interviewer.

“I thought, I’m wasting my life here,” he told Scott Carrier, a friend and public radio reporter, in 2005 while sitting in the backyard of Bowden's home near the University of Arizona. “I thought to myself, I’m going to go out and write the real history of my time on earth. . . I’ll write down all the stuff they think doesn’t matter that I think matters. I’m going to go out and create this endless book like Dickens did with his novels.”

When he first got back here, he mowed lawns, trimmed trees and did other manual labor for a living, said Mary Martha Miles, with whom he lived in the UA home for 12 years and who helped edit much of his later work. In the mid 1970s, he was a research assistant at UA’s Office of Arid Lands Studies, and also worked under a contract to produce a paper on Southwestern water problems.

His report, combining essay, polemic and narrative, hammered at the impacts of groundwater pumping and told how using groundwater transformed the Tohono O'odham tribe from “people who lived off the land to a people who happened to live on the land. . . The desert O’Odham moved from a society of abundance to a society of privation.”

UA never published the study.

Bowden, with $7.50 left in his checking account, brought the manuscript to Dannreuther, then a project manager and grant writer for the Tucson Public Library. She recalled reading the first page and thinking to herself, "This guy's going to be famous.

“Chuck had this amazing ability to bring together many disciplines: science, natural history, economics, ethnology, politics, etc., and coupled with his compelling writing ability, to create the perfect analysis of a very specific problem,” she said.

Ultimately, the University of Texas Press published the book, "Killing the Hidden Waters." It became an environmental classic, still in print today.

From 1981 to 1984, Bowden worked as a reporter and feature writer for the Tucson Citizen, specializing in pages-long examinations of problems that had generally been ignored. He wrote about victims of rape and child sexual assault and walked across the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge in southwest Arizona to dramatize the struggles of illegal immigrants crossing over from Mexico. Covering a 1983 eastern Arizona copper strike, he documented how the affair broke the union and fractured the community.

In 1984, a jury of journalists awarded him the Pulitzer Prize for feature writing, but the decision was overturned by the Pulitzers’ governing board.

“He brought a sensibility to his reporting that many journalists considered unorthodox, but it helped explain Tucson in ways that had never been done before,” author Zoellner said. “He wrote about nature in a rough-edged, almost violent sort of way and he framed otherwise kind of mundane questions about land use in starkly dramatic terms.”

In the mid-1980s, he quit the newspaper and helped found City Magazine, an investigative, literary publication that chronicled the environmental issues of Tucson’s growth and the city's seamy underside: rapists, drug dealers and sleazy politicians.

After it folded for financial reasons in 1989, he poured himself into books, mostly on the environment at first, but also the sordid tale of S&L king Charlie Keating. Keating did jail time after being convicted of bank fraud, racketeering and conspiracy for fleecing thousands of his institution’s investors out of hundreds of millions of dollars.

Bowden's environmental books chronicled what he saw as Mount Lemmon’s ecological decline under the assault of population growth. He also wrote eloquently of the Sonoran Desert’s harsh beauty.

Later, starting with the photo book “Juarez: The Laboratory of the Future” in 1998, and continuing into “Murder City,” “El Sicario” and “Dreamland” in the 2000s, he focused on drug wars, narcos, killings and the corruption of Mexican society. “El Sicario” told the story of a former Juarez hit man who Bowden and others persuaded to give eight hours of interviews recounting his role in Juarez’ endless drug-related murders and his religious conversion that led him to tell his story, said Molloy, Bowden’s co-researcher.

It was inevitable that Bowden would get as deeply enmeshed into the Mexican story as he did, author Weisman said. Weisman’s own borderlands book, "La Frontera," stemmed from field research in the mid-1980s, when he could cross the border with impunity, whether a formal crossing point or not. While narco-trafficking was taking place, "it was still a beautiful shared environment, a mostly safe place where a lot of ranches bordered each other on both sides and you just open a cattle gate," Weisman said.

By the time Bowden started going there, "it wasn’t so pretty anymore. The narcotraffickers were loaded to the gills. Stuff started happening in Juarez, there was no longer just a strongman here and a strongman there," Weisman said.

In explaining the book “Murder City” about Juarez’s endless killings, Bowden told a 2011 Southern California audience that he had dedicated it to a Juarez newspaper reporter, Armando Rodriguez, who was murdered in November 2008 in front of his house while warming up his car to take his daughter to school. It was one of 1,600 murders that year in Juarez.

“He had filed 907 stories that year of murders. He had basically been consumed by murders,” Bowden said.

“I wanted to assault the reader. I wanted to take no prisoners . . . and I didn’t want any simple answers, ” Bowden told the audience. He used the tales of three individual killings to raise bigger questions about the role of the North American Free Trade Agreement’s damage to the Mexican and the “disaster” of the U.S. war on drugs, blaming both for creating the climate making these killings possible.

For his efforts, he drew more than a few death threats and at times had to travel in Mexico with a bodyguard. More than a decade ago, his then-partner Mary Martha Miles was told by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration that Bowden had three contracts out on his life, she said. At home, "we had guns in every room and in the truck," she said.

Yet Bowden would get very frustrated with people who felt he was writing from a negative perspective, Miles said.

"He had a deep love of the Mexican people, of their land and anything that touched their lives," Miles said. "He wanted to make the world understand them and to care for them in the way he did. He felt that if the readers understood, they could help make changes."

PRIVATE LIFE

Bowden loved good food and good wine.

"Cookbooks were his pornography — he would go into Williams-Sonoma and fondle the pots and pans," Weisman said.

He would rise each morning at 3 or 4 a.m., write until midday, then get on the phone with sources and editors in New York City until 2 p.m., Miles said.

"He would go to the store and buy food for dinner, and he would open a bottle of wine and drink it every day, without exception," Miles said. "It physically was destroying him."

In his last few years, however, he cut back on his drinking, said Molloy. He was a near-chain smoker of unfiltered cigarettes for decades, but gave that up a few years ago.

Public radio’s Carrier, who recently was working on a magazine profile of Bowden for the environmental magazine High Country News, said the writer appeared to be in poor health when he last saw him about a month ago.

But he was lifting weights and going for long walks, hoping to finish one more article, Carrier said.

It’s impossible to say how many more of Bowden's books or articles will appear. Even in his final weeks, he was writing constantly. If he felt too bad to write, Molloy said, he’d research. If he was too weary to research, he’d polish something already written. If he was too sick for that, he would be reading – he’d read more books than anyone else she’s known.

In early August, Bowden was coughing a lot. A doctor diagnosed him with the flu and prescribed antibiotics that didn’t work, Molloy said. A hantavirus test proved negative, and he’d been scheduled to see a cardiologist on Sept. 3, just days before he died, she said.

He had finished at least one more book, a memoir-like effort called “Rhapsody.”

"It really is like a piece of music. ... In some ways, that’s how this reads," said Alice Leora Briggs, an artist in Lubbock, Texas, who collaborated with Bowden on it.

Mix together that poetic voice, that innate sense of social justice and that reportorial ability for observing and digging, and the result was combustible.

As author Weisman said, “He could take his sheer capacity for engagement with the world, combined with his out-sized gift for eloquence and his attraction for rawness, to talk about things far bigger than himself.”