Catherine Drexel was born Nov. 26, 1858, into a family of affluence and status. The Drexels of Philadelphia were known for their business acumen as well as their philanthropic activities.

Drexel considered it her destiny and duty to provide education for the most downtrodden races — Native Americans of the Southwest and African-Americans in the South.

Drexel was the second of three sisters. When their father died in 1885, the Drexel daughters became some of the wealthiest women in the country. Already making charitable donations to Indian missions, Katharine Drexel (as she became known in her adult life) and her sisters headed west in 1887.

Traveling to Indian reservations required stamina and a strong constitution since no railroads spanned the isolated regions occupied by most native communities. The sisters made their way by buckboard to the Rosebud School in South Dakota, a product of Katharine Drexel’s generosity.

In Pine Bluff, they met Red Cloud, one of the most important chiefs among the Sioux. Drexel had contributed to the building of a mission in Stephan, South Dakota, and was treated to an Indian dance not usually witnessed by outsiders.

She headed west again the following year to visit the Chippewa in Red Lake, Minnesota, and an Indian boarding school in White Earth, Montana. Drexel was already sponsoring 22 missions and subsidizing many others.

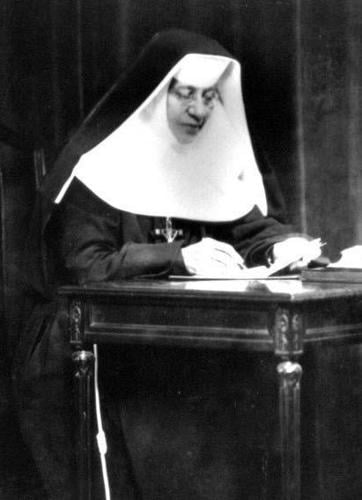

In 1889, Drexel entered the Sisters of Mercy order. Two years later, she started her own convent, the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament for Indians and Colored People, and began construction on a new convent in Cornwell Heights, Pennsylvania.

St. Elizabeth’s Convent was completed in 1892. Starting her own convent allowed Drexel to maintain control over her finances instead of turning her capital over to the church. Prejudice against Native Americans and African-Americans left her wary that her efforts to provide funds to those who needed her intervention would be ignored.

In 1895, Drexel purchased 200 acres in an area known as La Cienega Amarilla, just west of what would become the Arizona-New Mexico border, with the purpose of starting a school for Navajo children.

She made her first trip into Navajo country in 1900 to check on the planned school, and returned the following year to meet with respected Navajo elders to assure them the school she called St. Michael would soon open.

On Oct. 15, 1902, Sister Mary Evangelist from the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament boarded a train out of Philadelphia for Santa Fe. Evangelist would become the first Mother Superior of St. Michael School. Drexel, who was already in the West, met up with her along with Sisters Mary Angela and Mary Agatha, and they all headed for Gallup.

From Gallup, it was a five-hour buckboard ride to the reservation. Agatha found the rough, barren trail exhilarating. She wrote in her journal:

“During the long ride we saw four crows, two wagons and a few Indians. I think we enjoyed it very much as there was a great deal of laughing done, making up prayers in between times. We were almost pure white with dust, at least our shawls and veils were, and the sun poured down on us, but we were not the least troubled, because we were on the way to the Navajo.”

That night, the sisters slept on the floor of the unfinished schoolhouse. The next day, they followed workmen from room to room washing windows and hanging curtains in preparation for the opening of St. Michael. More sisters arrived from St. Elizabeth’s and almost every day, freight wagons pulled into the remote district with equipment and furnishings.

According to Father Anselm Weber, one of the Franciscan priests who would teach at the school, Drexel paid for everything, “even for horses and saddles and Mass wine.”

On Dec. 3, 1902, the first 24 students arrived at St. Michael. Enrollment increased steadily through the years, but the school was not without its share of troubles. A 1911 measles outbreak left 2 students dead, and a flash flood destroyed the school’s gardens and storage buildings.

In 1920, the influenza epidemic that spread around the world made its way to St. Michael, infecting more than 80 children. All but one recovered.

Yet there was plenty of time for fun, such as a baseball game Drexel attended between St. Michael and Fort Defiance employees. As the score remained close, two of the sisters headed for the chapel with one of them saying, “This is going to require some very serious praying.” And sure enough, Drexel said, “Prayer won the game.”

Drexel expanded her educational territory in Arizona by funding tuition for Tohono O’odham children to attend schools in Window Rock and on the Gila River Reservation. She also supported a Yaqui church south of Tucson and the Yaquis’ San Ignacio de Loyola at Chuama. She paid the salaries of teachers at San Xavier del Bac Mission School.

Drexel’s work with African-American students was just as passionate. She built St. Francis de Sales girls school in Virginia, Immaculate Mother Academy for black girls in Nashville, St. Monica School in Chicago, and Xavier University in New Orleans, the first all black Catholic college in the United States.

Drexel made her last trip to Arizona in 1935. She spent her remaining years at St. Elizabeth’s Convent.

On March 3, 1955, Reverend Mother Katharine Drexel died at the convent. It is estimated she spent over $20 million during her lifetime to educate Native American and African-American students.

Drexel’s cause for canonization was introduced in Rome in 1964. In 1987, she was declared venerable by Pope John Paul II and beatified in November 1988.

Eagle Dancers from the Laguna tribe performed in Rome, and a Navajo woman spoke the first Navajo ever used in a Vatican liturgy.

Drexel was formally canonized on Oct. 1, 2000. Her feast day is March 3.