We have left turns from Michigan and potholes from the pits of hell, but one local traffic oddity is an Old Pueblo original.

What do you call a road that runs diagonally between an east-west street and a north-south avenue? Here — and nowhere else in America, apparently — that’s known as a stravenue.

Pima County is home to 40 of them, mostly in mid-century neighborhoods built around Tucson’s angled arteries — Aviation Parkway, Benson Highway, the Union Pacific Railroad tracks and Interstate 10 east of I-19.

The U.S. Postal Service even has an official abbreviation for the stravenue (that would be STRA), though mail carriers outside of Southern Arizona don’t need to concern themselves with it.

“Our records indicate the name is only found in Tucson, Arizona,” said Roy Betts, national spokesman for the Postal Service.

Tracing the origins of a made-up word

So who is responsible for coining the term?

Wikipedia gives credit for the stravenue to “Mr. Tucson” himself, Roy P. Drachman, who reportedly dreamed it up in 1948 as part of Del Webb’s Pueblo Gardens development near 22nd Street and present-day Kino Parkway.

But don’t believe everything you read on the internet. The apparent source for that historical nugget is a reader comment posted beneath an Arizona Daily Star story from 2008, which is pretty thin gravy, even for an online encyclopedia.

Arizona Highways magazine featured Del Webb’s Tucson development, Pueblo Gardens, in the November, 1948 edition.

Recent research by historian and preservationist Demion Clinco points to a more likely candidate: another prominent Tucsonan who played a large role in the city’s post-war development.

Clinco said the earliest appearance of a stravenue he can find is on the plat map for a subdivision called Country Club Park, a wedge-shaped neighborhood hemmed in by Aviation Road, Country Club and 29th Street.

It features six stravenues that were mapped out in February 1948, three months before the plat for Pueblo Gardens.

The same land surveyor produced both maps: Tony A. Blanton from the Tucson architectural firm of Blanton and Cole.

In December 1948, Blanton submitted another plat map, this time for North Campbell Estates at Campbell and Glenn, and again there were stravenues.

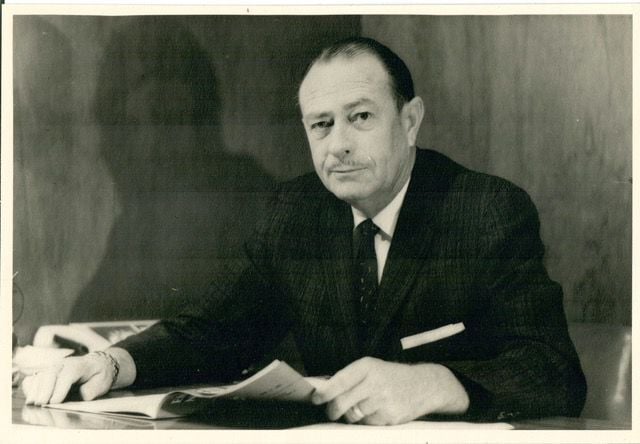

Planner and land surveyor Tony Blanton, ca. 1940s.

“Based on this, I think it would be fair to say Blanton brought us the stravenue,” Clinco said. “If he did not actually invent the term, he produced the first one and promoted their popularity in the late 1940s.”

Blanton helped put Tucson on the map

Longtime Tucson land surveyor Don Rockliffe said details like road names are often handled by the planner who is hired to draw up the subdivision map.

“Unless the developer had some pet names in mind, he left it up to the engineering firm to come up with the street names,” he said.

Of course, Rockliffe might be a little biased. Tony Blanton was his grandfather.

Rockliffe said his father, Donald Alan Rockliffe, married Blanton’s eldest daughter, Beverly, and worked as draftsman and design engineer for his father-in-law.

Tony Blanton, a prominent Tucson planner for decades, is a likely candidate for being the person who originated the term “stravenue.”

Blanton and Cole was one of Tucson’s first engineering and architectural companies, Rockliffe said, and it soon became the preeminent firm of its kind in the city.

By 1958, it had 42 employees and a newly built downtown office at Main Avenue and Pennington Street, though that building was lost to urban renewal about a decade later. “Now it’s buried beneath the county courthouse,” Rockliffe said.

Major local clients included the University of Arizona, several public school districts, Davis-Monthan Air Force Base and Hughes Aircraft Company. Blanton and Cole also worked on projects across Arizona and in eight other states.

Arizona Highways magazine featured Del Webb’s Tucson development, Pueblo Gardens, in the November 1948 edition. One “stravenue” origin story is that Roy P. Drachman reportedly dreamed it up in 1948 as part of Pueblo Gardens

.

From cowboy roots to the city’s “in-crowd”

Rockliffe said his grandfather was “part of the ‘in-crowd’ in Tucson, I guess you’d say, but he started out humble.”

He was born George Anthony Blanton in Calgary, Alberta, in 1910. His cowboy father was originally from Southern Arizona, and the family moved back here in 1911 — first to Willcox and then to Tucson in 1914.

After graduating from Tucson High School and studying at the UA, Blanton got his first engineering job with the Southern Pacific Railroad. He later worked for the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads, Pima County and the city of Tucson before launching a private practice with Frederick P. Cole, a former draftsman for the county.

Somewhere along the way, Blanton changed his legal signature to Tony A. Blanton — short (and somewhat redundant) for Tony Anthony Blanton.

Since learning of his family’s possible connection to Tucson road-naming lore, Rockliffe has done some research of his own that bolsters Clinco’s case.

He said there are 10 Tucson subdivisions that include stravenues, all of them mapped between 1948 and 1960. Blanton and Cole was the surveyor for six of them, including the five oldest.

Surveying streets runs in the family

The city planning and zoning commission added the made-up word to Tucson’s official street naming and numbering system in November 1948.

In May 1949, the Tucson Daily Citizen ran a piece explaining the new street type, which it described as “gobbledygood (sic) for diagonal.”

Tony Blanton rides a horse with his first child, Beverly, at his father’s ranch house on Hedrick Drive, near Campbell Avenue and Fort Lowell Road in 1936.

“I can remember seeing Cherrybell Stravenue as a child and thinking that was all so strange,” said Rockliffe, who retired in 2019 after 39 years as a land surveyor for Tucson Electric Power.

He never dreamed at the time that he might be related to the man who invented them — the man for whom Blanton Drive near Fort Lowell Road and Tucson Boulevard is now named.

Rockliffe said he used to visit his grandfather on Sundays and holidays. Occasionally, he would join him in his box seats at Hi Corbett Field for Cleveland Indians spring training games.

Blanton died in 1969 at the age of 59.

Rockliffe was about 11 at the time. Not long after, he began to learn the family business from his own father. He used to watch him work at his drafting table, and he later helped him draw a few subdivision plats before enrolling at the UA to become a registered professional land surveyor himself.

“He taught me surveying,” Rockliffe said of his dad, the likely son of the stravenue. “It felt like it was kind of in the blood.”