Tucsonan Bob De Armond will ring in the new year the same way he has for the past 50 of them: standing watch on a street filled with flowers in Pasadena, California.

Every year since 1973, De Armond has helped decorate floats for the famous Rose Bowl Parade on Jan. 1.

It’s one of the most unusual and intensive part-time jobs imaginable: roughly 95 hours of work crammed into the last five days of the year, culminating with an overnight shift in the parade’s staging area on Dec. 31.

“I have never been to a New Year’s Eve party,” the 76-year-old parade float supervisor said.

De Armond was joined in Pasadena this year by a crew of more than a dozen volunteer decorators he recruited in Tucson.

Rose Parade rules require every inch of every float to be covered with flowers or other plant parts, so he also took along file boxes filled with colorful local material to use on this year’s entry. One box was filled to the brim with 55 pounds of rusty red seeds that a volunteer collected during the heat of the summer from several Texas mountain laurel plants growing along the drive-thru lane of a fast food restaurant at El Con Center.

Each of those red seeds, no bigger than a marble, had to be glued onto this year’s float by hand.

De Armond volunteered for his first Rose Bowl Parade in 1973, shortly after he moved to the Los Angeles suburb of Torrance, California.

He said he didn’t really know anyone in Torrance, so when he saw a notice in the local paper inviting people to come help decorate the city’s parade float he signed up as a way to meet people.

“I’d been a fan of the parade for a long time,” he said.

That first float he worked on was a collaboration between the City of Torrance and the U.S. Forest Service, featuring Smokey Bear, Woodsy Owl and several trees in different colors, representing the four seasons.

De Armond was only supposed to help out for one day, but he impressed his supervisor so much she arranged to have him come back for the rest of the week.

“I took to it right away,” he said.

Petal power

Within a few years, De Armond was promoted to supervisor and paid to oversee all the decorating for the city’s annual Rose Parade float. He also served on the board of directors for the Torrance Rose Float Association, including two terms as president.

He even helped drive the city’s float for about six years.

The parade route only covers about 5½ miles, De Armond said, but “depending on where you are in the lineup, sometimes you’re in that thing for about five or six hours.”

Most of the time, the driver is sitting or lying down on two pieces of plywood no more than about 6 inches above the pavement, he said.

But every design is different. One year, De Armond controlled the gas pedal from one part of the float, while someone else in another part operated the brakes and the steering wheel.

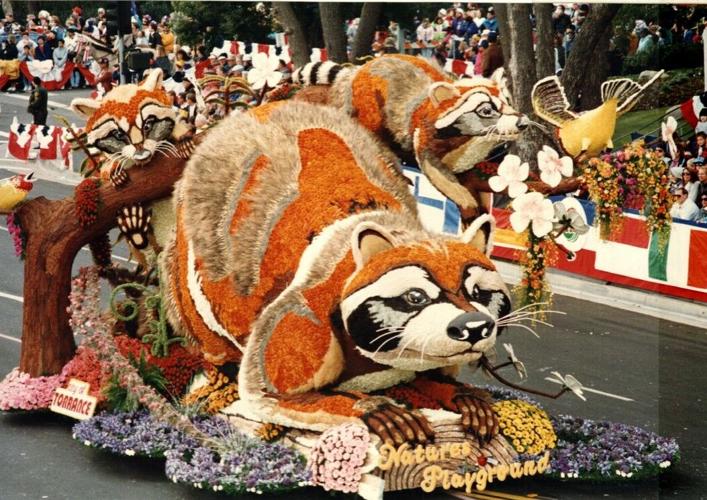

Another year, he had to lie down and look out through the nose of a giant raccoon so he could serve as a spotter for the float’s driver. That’s when sleep deprivation got the better of him.

“In front of us was an all-girls band from Japan that played the same song over and over, and their flags were going like this the whole time,” he said, motioning with his hands in front of his face.

Thoroughly hypnotized, De Armond dozed off, only to be awakened after an unknown amount of time by the voice of a parade official in his headset, warning him that their float was getting too close to the entry ahead of them.

Luckily, the floats only have a maximum speed of 2 or 3 mph.

“I could have caused an international incident,” he said with a laugh. “I was wide awake the rest of the parade, let me tell you.”

He decided to quit driving the floats and stick to decorating them after that.

Since the early 1990s, De Armond has worked as a seasonal supervisor for Fiesta Parade Floats, the most experienced and award-winning float building company associated with the Tournament of Roses. During that time, he has overseen the decoration of parade entries for several different California cities and huge commercial floats costing several hundred thousand dollars for major retailers like Target and Lowe’s.

Tim Estes, president of Fiesta Parade Floats, described De Armond as a conscientious and passionate supervisor and a great mentor who has “always loved the Rose Parade to death.”

Fiesta owes its success to “dedicated people like Bob,” Estes said. “It’s all for the love of the Rose Parade, because it sure isn’t for the money.”

Floral frenzy

De Armond’s entry in the 135th Rose Parade on Monday features a giant Mardi Gras jester that will dance above several live musicians as they ride along and play on flower-covered stages colored purple, green and gold. It’s the second year in a row he has been assigned to a float from the State of Lousiana’s tourism bureau.

“It’s kind of interesting because my mom’s birthday was Jan. 1, and she was from Louisiana,” he said. “I used to tell her, ‘You get the best flower bouquet from your son for your birthday that anybody ever gave.’”

As far as De Armond is concerned, decorating floats is just an extension of the kind of artistic work he has always done. “My whole life has been creating designs, so it’s just kind of a natural thing for me,” he said.

He spent his 45-year professsional career with HF Coors, a wholesale dishware manufacturer where he created and painted patterns on more than a million dishes.

When the company relocated from California to Tucson almost 20 years ago, he went with it, but he continued his annual, post-Christmas trek to Pasadena to work on parade floats. “I told my boss when I moved here, one of the stipulations is I get that week off so I can go back and do that,” he said.

He retired from his job as HF Coors’ art director about six years ago, but he continues to nurture his creative side as staff artist at Santa Theresa Tile Works downtown.

De Armond generally heads for California on the day after Christmas, but the float decoration work starts long before he gets there. In November, workers begin cutting up piles of dry strawflower confetti and cleaning the hundreds of thousands of little plastic vials that the roses go in.

For outsiders, the scale of the operation can be hard to comprehend. De Armond said there is a crew of 200 to 300 people in the float-building area, and all they do for a week leading up to the parade is trim roses to specific heights and stick them in those water-filled vials — a process known as “vialing.”

“They say that the average float has more flowers than a really good florist shop will use in a year,” De Armond said. “I’ve had ones that had 80,000 to 90,000 roses on them.”

The frames holding up all those flowers are made from pencil steel mounted to I-beams like you’d find in a skyscraper, he said. “We’ve had some floats that were so heavy that the tires had to be filled with sand so they wouldn’t collapse.”

Each entry is meticulously planned out in advance. De Armond doesn’t design them himself, though he does weigh in along the way.

Then it’s up to him and his crew to execute — and occasionally elaborate on — the overall vision. “With the detail stuff, I have a lot of leeway,” he said. “In the (instruction) book my boss will say, ‘Fill in as needed, see Bob.’”

Rose regulars

Throughout the hectic decorating process, De Armond has to direct a shifting crew of 50 to 60 volunteers a day. Many of his workers are Girl Scouts, just there for a day or two, but he also relies on a seasoned team of Rose Bowl regulars.

“I have a lot of people that have been decorating with me for many years,” De Armond said. “I have people that fly in from Canada, and this one couple, they come out every three or four years from Columbus, Ohio and work with me. It’s kind of like a family reunion every year with friends.”

A few people volunteered with him as teenagers, then showed back up decades later with teenaged children of their own.

“My group and I are known for real intricate detail,” De Armond said. “I keep getting floats with really crazy details, because all of my regulars really like doing stuff like putting beans on one by one and stuff like that.”

One year, De Armond and company were tasked with decorating a float for the City of Azusa, California, that included a large brown-and-white street sign for historic Route 66.

“Two ladies spent the whole week doing that sign. The white I had them do with grains of rice one by one with tweezers in perfect straight lines, and the brown was little tiny flax seeds put on like that,” he said. “Nobody would notice, even from the curb, that it was done that way. But you’re trying to impress the judges.”

And it worked, too. Azusa’s float took home a technical award that year, beating out several, far more expensive, corporate entries.

De Armond is always on the lookout for interesting new materials to use in the parade. He once visited a friend’s farm in Nebraska and came home with a suitcase full of cornhusks for a float he was working on. He has also been known to harvest the orange-tufted beans from the inside of giant bird of paradise flowers to use as decorations.

To give something a weathered or antique look, sometimes De Armond will spray it with glue, then use his own breath to blow on a dusty layer of cinnamon or finely chopped dill weed.

He said his favorite float was one he decorated with a Day of the Dead theme, “which was kind of weird for conservative Pasadena.” The tallest float he’s worked on topped out at 55 feet, roughly the height of a five-story building.

De Armond said he’s had no major mishaps in 50 years of float-making, though he did have to improvise one year when a behind-the-scenes political fight in a Southern California city caused the funding for the float to suddenly dry up.

It was too late to drop the entry from the parade, so they built as much of it as they could. The display was supposed to feature three fighter jets soaring over a family of antelopes, but they ended up with just two jets and a single animal.

With no money for flowers, large areas set aside for floral arrangements were decorated instead with plants De Armond picked from along some nearby train tracks or whatever he could salvage from the trash bins of other float builders.

“We ended up winning the award for best small float and everybody was freaked out that we did,” he said. “That was the most satisfying.”

Ready to float

Traditionally, Dec. 31 is moving day for the float builders of Pasadena. That’s when the finished creations are driven over and parked along Orange Grove Boulevard, where the supervisors will repair any damage sustained during transit.

One year, De Armond spent a good chunk of his night fixing a fairy on his float that got beheaded by a low-hanging obstruction on its way to the staging area.

Float workers also have to stand guard over their entries as they sit there overnight on the public street.

“It’s New Year’s Eve, so you have to keep all the inebriated people from pulling flowers off your float,” De Armond said. “You don’t get any sleep.”

Since he isn’t driving floats anymore, though, he does get to relax a bit on Monday morning and take part in a New Year’s Day tradition at a friend’s house near the parade route.

Every year, he said, a group of float supervisors from different companies all get together to eat breakfast, watch the parade and “make fun of each other’s stuff.” Then they all pile into a car and drive to the end of the route to meet the floats as they come in and catch up with more of their colleagues.

De Armond said such camaraderie and creativity are what keeps him coming back year after year, despite all the pressure and exhaustion that comes with the Rose Bowl Parade float business.

“You either really, really like it,” he said, “or you don’t want to do it at all.”