PHOENIX — Immigrant-rights groups are giving up their bid to void the “papers, please” provision of Arizona’s controversial SB 1070 in exchange for some state-issued informal — and non-binding — guidance on how police should enforce it.

In an agreement filed in federal court Thursday, the organizations are dropping their appeal of a ruling last year by U.S. District Judge Susan Bolton that there is nothing inherently illegal about the provision in the 2010 law requiring that police officers, when possible, check the immigration status of people they have stopped for any other reason.

Foes had tried to show the law was racially motivated. But Bolton said while it may be that most of the people affected in Arizona are Hispanic, the law itself is racially neutral.

In exchange, the state Attorney General’s Office is issuing an informal legal opinion spelling out for police officers how they can — and cannot — enforce the statute. That will include cautions against racial profiling.

Potentially more significant, it will remind officers that they cannot detain anyone for longer than necessary for the original reason they were stopped.

That means no delay while waiting for a radioed response from federal immigration agencies about whether the person is legally entitled to be in this country. And it also means that even if the person is not here legally, police cannot keep them from leaving while awaiting an immigration officer to come and take custody unless they are under arrest for some state offense.

As an informal opinion, though, it cannot be used to bring actions against police who do not follow the guidelines. But Victor Viramontes, senior counsel for the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Foundation said it will have some value when some police department decides it wants to try to take action against those not here legally.

“Exhibit A is going to be the state of Arizona saying what the constitutional limitation of local law enforcement is,” he said, saying it will be a “useful tool” that can be used against a “rogue” police department.

Karen Tumlin of the National Immigration Law Center said it’s even more important than that.

“This law was a racist attempt to marginalize Latino and Asian-American communities, to make them feel isolated and, ultimately, to drive them out of the state,” she said.

That’s not an exaggeration.

The legislation itself declared its intent was “to make attrition through enforcement the public policy” of Arizona. And it says the provisions would “work together to discourage and deter the unlawful entry and presence of aliens and economic activity by persons unlawfully present in the United States.”

Tumlin said the written legal opinion makes it clear that, whatever the intent of the original sponsors, Arizona is now on record as saying the law cannot be used to target those not here legally to drive them from the country.

And Cecillia Wang of the American Civil Liberties Union praised Attorney General Mark Brnovich for being “the first state official in Arizona to say, ‘I acknowledge these limits.’”

Not everyone sees the decision to drop the challenge as a good thing.

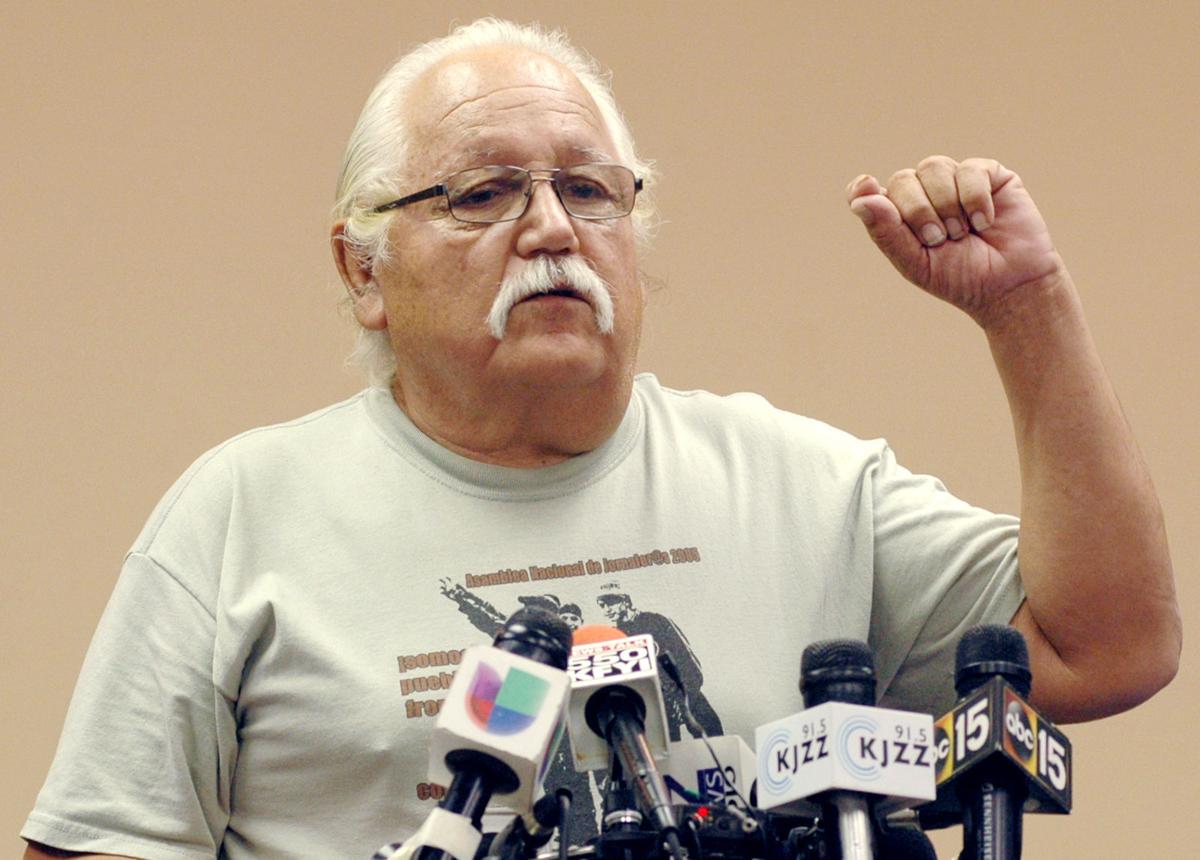

“Racial profiling has been instituted into law,” said Latino activist Salvador Reza. He said it keeps on the books an excuse for police to use some pretext to harass people they believe are in the country illegally.

“That means that any police officer can stop you and make up stories,” he said.

Reza said the only good thing to come out of the deal is the state is giving up trying to resurrect another provision of SB 1070 aimed at day laborers.

That law would have made it a crime for someone to stop a motor vehicle on a street and impede traffic in attempting to hire someone to work at another location. It also would have made it illegal for someone looking for work to enter such a vehicle.

Arizona had not been enforcing that because a federal appeals court had issued a preliminary injunction even before Bolton’s 2015 ruling.

While the deal announced Thursday ends the last bit of this lawsuit, it does not mean there will be no future battles over SB 1070 and allegations of racial profiling.

Bolton, in refusing to void the “papers, please” provision, said only that the law is facially valid because there are ways of enforcing it which do not single out Hispanics or other minority groups.

“Plaintiffs have admittedly not produced any evidence that state law enforcement officials will enforce SB 1070 differently for Latinos than a similarly situated person of another race or ethnicity,” the judge wrote.

But Alessandra Soler, executive director of the Arizona chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union noted that what was not before the judge — and what remains an option — is an “as-applied” challenge, where evidence is presented that a police agency enforces the law in a discriminatory fashion. Soler said the groups that challenged SB 1070 will continue to monitor what happens in Arizona and will file a new lawsuit if such discrimination occurs.

Brnovich said he hopes that the informal opinion ensures that does not happen.

“I don’t want any law enforcement official, whether they work for me or another law enforcement agency, to be racially profiling,” he said. “I don’t want law enforcement officials to be unnecessarily detaining people inconsistent with Supreme Court precedent.”

This deal comes nearly two years after the U.S. Department of Justice, which had filed a lawsuit against SB 1070, dropped its bid to void the “papers, please” provision.

That, too, involved a deal: Arizona gave up its efforts enforce another provision which would have made it a state crime to knowingly transport or harbor someone in this county illegally, and made it illegal to “encourage or induce” someone to come to or reside in Arizona if they have no legal right to be in the country.

With today’s announcement, the six-year battle over the divisive law that gained national attention is finally over.

The act’s approval by the Republican-controlled Legislature and signature by then-Gov. Jan Brewer drew national attention. It also resulted in demonstrations and boycotts, with officials in the state’s tourism industry reporting a loss in the number of conventions and conferences scheduled here.

But it also made Brewer, who had inherited the office the year before after Janet Napolitano quit as governor, a national figure. And it likely helped her win a term of her own in the 2010 election.