A contractor that helped prepare a key federal environmental report for the proposed $2 billion SunZia power line had past ties to a major project investor — and works for SunZia today.

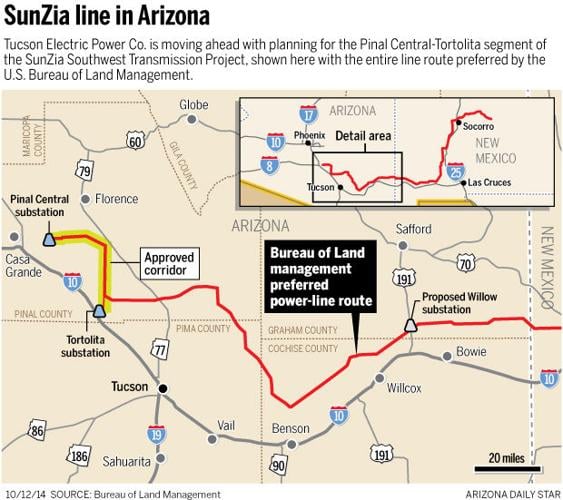

The Environmental Planning Group, a Phoenix-based consulting firm known as EPG, was the federal contractor for the environmental impact statement for the two high-voltage power lines planned to run from central New Mexico through Southeast and Central Arizona, crossing the Lower San Pedro River Valley near Tucson.

The U.S. Bureau of Land Management signed off on the controversial route in January 2015, about a year before the Arizona Corporation Commission approved construction in this state. EPG’s ties to SunZia have drawn conflict-of-interest concerns from critics of the project, but company officials and the BLM say the concerns aren’t justified.

SunZia’s backer, a Phoenix-based consortium of five investors called SunZia Transmission LLC, hopes to start construction in 2018 and finish the first power line in 2021. Opponents are considering legal action to try to stop the project.

Opponents say the federal environmental review is tainted in part because a panel of mostly SunZia officials recommended EPG’s hiring to the Bureau of Land Management. Opponents are also concerned about links between the company and SunZia and its investors, some going back to the years before EPG won a federal contract in 2009 to work on the environmental report.

Echoing those concerns is Patrick Parenteau, a Vermont Law School professor and former top attorney for the Environmental Protection Agency, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and National Wildlife Federation. He teaches classes on the National Environmental Policy Act, which governs the preparation of environmental impact statements and was founder of the law school’s environmental law clinic.

While it’s difficult to prove a federal agency is biased in its handling of a particular case, the BLM’s performance gives the impression of bias and conflict of interest, said Parenteau. He has litigated more than a dozen cases involving the Environmental Policy Act for the wildlife federation and for his school’s environmental law clinic.

Carrying out the environmental law “relies on good faith, objective, hard-look analysis” of proposed projects, he said. Federal agencies are required to make decisions in the best interest of the public, Parenteau said. “The whole process breaks down when parties with a direct stake in the outcome are in charge of assembling the facts.”

BLM and a top official from the Environmental Planning Group deny any impropriety. The bureau found EPG to be the best-qualified applicant and determined it had no financial interest in SunZia at the time it was hired. Its officials did their own review before hiring the firm.

EPG has worked on more than 100 projects involving electrical infrastructure, including power plants and transmission lines, said Mickey Siegel, a principal and project manager for the firm. It has done consulting work on issues related to the National Environmental Policy Act for 10 federal agencies besides the BLM. The act, known as NEPA, sets ground rules for how environmental impact statements should be written.

The bureau, not EPG, managed the environmental review, BLM officials said.

“Throughout the project, the BLM openly disclosed EPG’s role as the third-party contractor,” the bureau said in a written statement to the Star. “EPG’s role was clearly identified at scoping meetings, on public display boards, on draft documents.”

Even if there were a conflict of interest, it’s difficult to get judges to overturn an agency’s approval of a project on that basis, Parenteau said. An opponent usually must prove the agency was overtly biased and that key problems or issues were overlooked, he said.

CRITICS’ CONCERNS

These actions have drawn concerns from critics of the project:

- SunZia employed four of five members of a panel that reviewed applicants to help prepare the environmental report.

- BLM failed to disclose in its draft environmental report that the Environmental Planning Group had provided information for a map and done feasibility work for the SunZia project more than a year before it won the BLM contract — despite a federal Council on Environmental Quality recommendation that it make such a disclosure.

- EPG continues to work with the bureau on behalf of SunZia today, helping the bureau and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service prepare a bird mitigation plan for the project. EPG says it’s only follow-up work based on information it gathered when the environmental report was prepared.

- EPG worked for a prime investor in the SunZia project — Southwestern Power Group — from 2000 to within three years of when it won the BLM contract to prepare the environmental impact statement in 2009.

- In 2008, when SunZia prepared a request for qualifications for the BLM contractor on the environmental impact statement, it said the company winning the contract could also help SunZia obtain permits from Arizona, New Mexico and federal agencies. Critics see that as a promise of future work for SunZia, but the BLM and EPG say it wasn’t a promise of future employment.

PRIVATE COMPANIES’ role

Agencies such as the BLM and the Forest Service commonly hire private companies to help prepare environmental impact statements because they lack the staff or resources to do all the work themselves.

But the bureau chose EPG after hearing from an advisory panel of five: four SunZia officials, including project manager Tom Wray, and an independent consultant. The panel narrowed five applicants to two and recommended EPG over the second applicant, David Evans and Associates.

By contrast, when the Forest Service hired a third-party contractor in 2008 to help it prepare the Rosemont Mine environmental impact statement, it picked SWCA, a company with no ties to Augusta Resource Corp., the Canadian company proposing at the time to build the equally controversial copper mine in the Santa Rita Mountains.

With SunZia, the company-dominated advisory panel chose EPG, although Evans ranked slightly higher in the panel’s numerical scoring and would charge 17 to 21 percent less than EPG.

The panel concluded EPG had more experience getting permits for large power lines in the West and was more knowledgeable about the SunZia project area. In addition, SunZia’s experience should enable it to do the work for less than Evans would ultimately charge, the review panel concluded.

A core problem with conflict-of-interest rules is that — if applied too strictly — they can eliminate the most-qualified firms, law professor Parenteau acknowledged. But the bureau was on shaky legal ground by relying on an outside panel with such close ties to SunZia, he said. Regulations are explicit that a contractor must be selected solely by a lead agency such as the BLM or by that agency in cooperation with other agencies, he said.

“Choosing a contractor recommended by a group dominated by employees of the applicant raises serious questions of actual conflict of interest or at the very least the appearance of impropriety,” he said.

Peter Else, a Mammoth resident and a leader of those opposing the power lines, said he believes SunZia essentially chose EPG as the contractor.

“The National Environmental Policy Act has been subverted to the point that SunZia was allowed to subcontract the federal permit process to an environmental firm they had in their back pocket,” Else said.

The BLM said Else is wrong. After the outside review panel made its recommendation, it convened a team of four BLM specialists to evaluate contractor applicants. That team picked EPG based on its qualifications, the bureau said.

“To be clear, as required … the BLM made the final and sole decision as lead agency on the EIS contractor selection,” the bureau said in a written statement.

It’s common for contractors hired to do environmental impact statements to work on various projects over time by related companies or agencies, the BLM said. Federal regulations require that any contractor performing such a report write a disclosure statement specifying it has no “financial or other interest in the outcome of the project.” EPG did that in February 2009, the BLM said.

Else criticized the bureau and EPG for failing to disclose the company’s past ties to SunZia and its investor, the Southwestern Power Group, in the draft environmental report.

Else learned of the SunZia-dominated advisory panel last fall in response to a request for public records on the selection process he obtained through the federal Freedom of Information Act. None of the records he received at the time mentioned the BLM team that made final recommendations, he said.

Apparently, “BLM never asked the applicant if the contractor had ever worked for the applicant, they never asked questions. They told you they had a committee that met, but had no documentation of what the committee did. That’s not due diligence,” Else said.

In response, the BLM said that when it signed its agreement with the Environmental Planning Group, it “was not aware that EPG had conducted any previous work for SunZia.” The bureau said it did not learn of the prior ties until after it had signed an agreement to work with the company.

Siegel, however, said the bureau knew EPG had done feasibility work on earlier versions of the SunZia project, for the Southwestern Power Group. SunZia did not include those versions in its application to BLM to build the power line on federal land.

Siegel said the bureau met all requirements for disclosure under the National Environmental Policy Act, which governs the preparation of environmental impact statements.

FUTURE WORK?

SunZia’s 2008 request for contractors for the environmental report specified twice that the contractor would also help get other permits and government approvals. Among them: Arizona and New Mexico approvals, clean water and air-quality permits, a conditional-use permit and a Federal Aviation Administration permit.

“It’s obvious that somebody is going to give the employer the answer they want if they are going to get future work,” Parenteau said. “It’s just human nature.”

A federal district court judge has ruled that “a contractor with an agreement, enforceable promise or guarantee of future work has a conflict of interest” under federal law, Parenteau said. SunZia’s request came “awfully close to a ‘guarantee of future work,’” he said. “It’s at least an offer of future work.”

EPG’s Siegel said there was no promise of future work because, “When the schedule was laid out originally, all those processes were scheduled to run concurrently.” But some permits weren’t approved for years, such as the Arizona Corporation Commission certificate obtained last month, he said.

All the information gathered during the early work on the BLM environmental report was used in other permit applications later, he said, including some that are still pending.

“It was clearly disclosed that those efforts would be done during the EIS (environmental impact statement) process, not necessarily that everything on the list would be completed in that time,” Siegel said.

In statements to the Star, the BLM didn’t respond directly to questions about possible future employment guarantees, other than to refer to a third page in SunZia’s 2008 request for contractors that said the contractor “may” help SunZia get the other permits.

The BLM said it isn’t aware of “any prohibited financial or other interest in the outcome of the project on behalf of EPG. EPG’s disclosure statement complied with the BLM’s requirements. In addition, NEPA regulations do not prohibit a third-party contractor from completing later work on the same project for the project proponent.”

The project’s future now moves to New Mexico, where the power-line company needs the Public Regulation Commission — the equivalent of the Arizona Corporation Commission — to grant a certificate allowing the lines’ construction there. In Arizona, opponents have filed an application with the ACC to rehear the case. And they may file suit against the BLM, arguing that its process for approving the environmental review was rigged in favor of SunZia.