Tucson-based NASA scientist Chad Greene made his first trip to Greenland earlier this year to test a special high-resolution radar designed to peer through the ice from an airplane and map the bedrock underneath.

Imagine his surprise when the device also captured a detailed image of an especially cold Cold War relic.

During a test flight over northern Greenland on April 24, Greene and his fellow researchers happened across the location of Camp Century, a subsurface research station that was carved into the ice sheet by the U.S. Army starting in 1959.

The so-called “city under the ice” was powered by a nuclear reactor and housed up to 200 men during its eight years of operation roughly 780 miles from the North Pole.

A government photo taken in 1960 shows a metal-arch roof being placed over a trench during construction of Camp Century, the U.S. Army’s attempt to establish a subsurface ice base in northern Greenland.

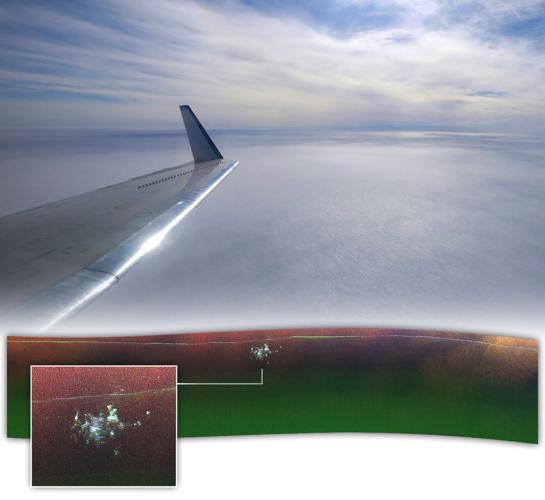

The site now lies more than 100 feet below the surface, buried beneath a layer of snow and ice that has been gradually growing since the facility was abandoned in 1967. Yet there it is — buildings, tunnels and all — in an almost 3-dimensional picture captured by NASA’s Uninhabited Aerial Vehicle Synthetic Aperture Radar.

A NASA Earth Observatory graphic shows an aerial view of northern Greenland with a high-resolution, ice-penetrating radar image of Camp Century (inset), a nuclear-powered base the U.S. Army operated from 1959 to 1967. The image was created using data provided by NASA’s Chad Greene and Joseph MacGregor.

“We weren’t expecting to be able to see it in such great detail,” said Greene, a climate researcher with the space agency’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

NASA’s popular Earth Observatory website made the radar signature of Camp Century its “Image of the Day” on Nov. 25.

Greene said the image represents “proof of concept” for the radar system, which could become a powerful new tool in the effort to chart the impacts of climate change.

“Can it map the ice bed? Yes it can,” he said.

Project Iceworm

As the Cold War heated up in the late 1950s, the Army sought to establish an outpost on the Greenland ice sheet, about 150 miles inland from what was then Thule Air Base, to test arctic construction methods and the utility of mobile nuclear power plants.

Trenches were dug up to 26 feet deep and covered with steel-arch roofs, forming tunnels in which prefabricated buildings were assembled. There were 21 tunnels in all, with a total length of almost two miles.

The reactor that powered the camp was towed across the ice sheet from the coast on a huge, specially built sled.

The U.S. military began construction without the approval of the Kingdom of Denmark, which governs the island territory triple the size of Texas and its roughly 56,000 residents.

An aerial photo of Greenland taken by NASA climate researcher and Tucson resident Chad Greene during a series of scientific test flights in April.

Camp Century was continuously occupied until 1964, when it switched to seasonal operations for three years after that.

The facility ostensibly served as a scientific research station and a testing ground for ice-cap military operations.

Its true purpose wasn’t revealed to the public until 1996, when documents were declassified on Project Iceworm, a secret military plan to deploy as many as 600 nuclear missiles in silos scattered across the Greenland ice sheet.

“The project was considered favorably in the higher echelons of the Kennedy Administration, who were cautiously optimistic concerning the possibility of getting the necessary consent from the Danish Government,” wrote historian Nikolaj Petersen in 2007. “An analysis of Denmark’s nuclear policy demonstrates the utter lack of realism of this assumption.”

Pentagon officials eventually shut down Project Iceworm, not for the sake of international relations but for technical reasons. As those at Camp Century learned as their tunnels gradually closed in around them, the Greenland ice sheet is simply too unstable to make long-term subsurface facilities feasible.

The nuclear missiles were never deployed and the scheme was never discussed with the leaders of Denmark.

Down to the core

But not all of the research at Camp Century was top secret.

In 1966, the U.S. Army Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory completed a three-year effort to drill through the entire Greenland ice sheet, producing a core sample about 4 inches in diameter and nearly a mile long.

That ice core is now famous, at least in the paleoclimate community, Greene said.

Researchers have used the core to reconstruct the temperature and precipitation record of Greenland going back about 20,000 years, and it is still being kept frozen inside the U.S. National Science Foundation Ice Core Facility in Colorado.

“The ice at the bottom of the Camp Century ice core is about 100,000 years old,” said Greene, who moved to Tucson in 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic made him a remote worker.

Tucson-based climate scientist Chad Greene poses with a NASA research aircraft at Pituffik Space Base in Greenland during two weeks of test flights in April.

Ice is the focus of much of Greene’s climate research.

During his first field season in Antarctica in late 2012 and early 2013, he spent several weeks camped in a one-man tent “a thousand miles from anything,” he said.

The glaciologist returned to the southern continent in 2018, this time to study ice sheets from the air in a World War II-era DC-3 with skis on its wheels and a cabin filled with high-tech instruments.

Four years later, he teamed up with his NASA JPL colleague, Alex Gardner, and others on a study that made international headlines by documenting the loss of some 14,710 square miles of protective ice shelf from the perimeter of Antarctica since 1997.

He and Gardner followed that up early this year with another bleak report charting the ravages of global warming, this time in Greenland, where an analysis of historic satellite images shows that since 1985, the ice sheet has shrunk by an extra 1 trillion metric tons of ice, about 20% more than previously thought.

A ‘stunning’ scene

Greene’s two weeks of test flights in April marked his first in-person visit to Greenland, and he was blown away by the dramatic landscape of mountains with rivers of ice flowing out of them. “It’s absolutely stunning,” he said.

The flights in a NASA Gulfstream III jet with the special radar mounted to its belly were conducted out of Pituffik Space Base, formerly Thule Air Base, on Greenland’s northwestern coast.

Greene said the goal was to see if the radar system could be used to produce detailed maps of the area where the ice sheet meets the bedrock, a mile down or so. Such information can help scientists measure ice sheets and estimate how they might move.

Aerial photos of Greenland taken by NASA climate researcher and Tucson resident Chad Greene during a series of scientific test flights in April.

Flying over Camp Century — let alone scanning it with the radar — was a happy accident.

As you might imagine, Greene said, the extreme and unpredictable weather in Greenland can make aerial science a challenge. “We made 25 different flight plans in hopes of getting four of them done,” he said.

One of those successful flights just happened to take them over the site of the old base, so Greene snapped a picture out the window of the aircraft to pair with the radar image of what was hidden beneath.

Eventually, Greene and Gardner want NASA to send the Gulfstream to the South Pole, so the special radar can be used to assess the thickness and overall condition of Antarctica’s most crucial stockpiles of ice in the face of human-caused climate change.

Scientists are especially worried about the ice shelves fronting two massive glaciers at the western edge of the continent. Should those shelves fail, there could be nothing to prevent slabs of inland ice more than a mile thick from sliding into the ocean, destabilizing the entire West Antarctic Ice Sheet and triggering a potentially catastrophic rise in global sea levels.

“It’s one of the climate tipping points a lot of people are concerned about,” Greene said.

By mapping the ice and the bedrock it is sitting on, scientists may be able to answer two vitally important questions, he said: “How much sea level rise are we going to have, and how quickly is it going to happen?”

Cold comfort

Ultimately, Greene said, “logistics and funding” will determine when NASA might deploy the radar system to Antarctica to start the mapping process there.

“I wish I could set the timeline,” said the scientist, who has used his four years in Tucson to grow a mustache and record a “hipster country” album called “The Iceman Strummeth.” “If I could, we’d be going tomorrow.”

An aerial photo of Greenland taken by NASA climate researcher and Tucson resident Chad Greene during a series of scientific test flights in April.

Global warming also poses a threat to the Greenland ice sheet and to the remnants of Camp Century specifically.

Though the nuclear reactor was removed from the site in the late 1960s, a substantial amount of radioactive waste, diesel fuel and raw sewage was abandoned under the ice along with the military outpost. Those pollutants could be exposed or carried away in meltwater as the ice sheet shrinks.

An international study in 2016 suggested the build-up of snow and ice over the camp could reverse itself — with net accumulation giving way to net ablation — within the next 80 years.

Camp Century in northern Greenland as it looked in 1966. The so-called “city under the ice” was built by the U.S. Army in 1959 and abandoned in 1967, after the nuclear reactor used to power the camp was removed.

In response to concerns from officials in Greenland, the Danish government launched a long-term environmental monitoring program at the site in 2017.

Worries about contamination have eased since then, thanks to a subsequent study in 2021 that concluded there is “no risk” of the camp’s ruins emerging from the ice or being breached by meltwater before the turn of the century.