Studying glaciers in a warming world could make anyone sing the blues, but Chad Greene’s songs have more of a folk-country sound.

The Tucson-based scientist and moonlighting musician is set to release his debut EP next month, a six-song collection aptly titled “The Iceman Strummeth.”

At the moment, though, Greene is getting more attention for his day job with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

The singing scientist just authored a startling new study charting the retreat of glaciers in Greenland, where the world’s second largest concentration of ice is now shrinking at an alarming rate.

Greene and his JPL colleague and co-author, Alex Gardner, analyzed decades worth of satellite images to determine that the Greenland Ice Sheet has shed an extra 1 trillion metric tons of ice, about 20% more ice than previously thought, since 1985.

Their findings with Michael Wood from San Jose State University and Joshua Cuzzone of UCLA were published in the journal Nature on Jan. 17 and picked up by major media outlets around the world. Greene was interviewed on air by CNN, Gardner by Australia’s national television news service.

“I wasn’t expecting such a response to this one, but it’s been huge,” Greene said of the paper. “We’ve been getting so many of these sobering reports for so long that you never know when people are saturated. But fortunately, it’s getting coverage, so there’s still interest and it’s still resonating with people.”

Even Rolling Stone magazine wrote about the study — and tossed in a plug for Greene’s upcoming album in the process.

“The Iceman Strummeth” will be released on Feb. 23 on streaming platforms, vinyl and as a digital download through Greene’s bandcamp page.

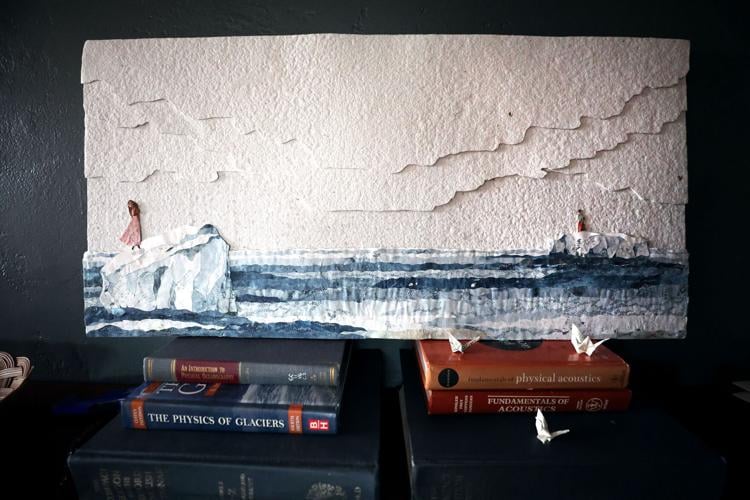

The album artwork for Chad Greene's debut album "The Iceman Strummeth" features an original collage, seen here Jan. 24, by Tucson artist Elana Bloom.

The songs drip with loneliness and heartbreak, though the artist insists he wasn’t channeling his work on the frontlines of the climate crisis when he wrote them.

“I think I have the good fortune to somewhat be able to compartmentalize, and as a scientist, you really have to do that,” Greene said. “You have to be able to emotionally separate what you’re feeling from what you’re finding.”

Music provides a much-needed creative outlet, a way to express himself outside of his “this-is-what-the numbers-are thing at work,” he said.

Still, the 39-year-old struggles with the abstract sometimes.

“I think if anything, I’m too much of a scientist in my songwriting, because I have to understand how every lyric makes sense. I have other musician friends who feel free to just write things that make no sense whatsoever — it’s just words; it’s fun — but I need to figure out the logic” behind it.

Behind the music

Greene grew up in rural Virginia and has been playing music most of his life. He started as a jazz drummer in high school and played in a jazz quartet called The Hot Tubs in college.

“Then in my 20s, I drifted more toward guitar, just like every other millennial hipster,” he said with a laugh. “Really, it’s just been a hobby.”

Greene moved to Tucson in 2020, after COVID-19 shut down the JPL offices in Pasadena, California, sending him in search of a new homebase for remote work. He said some of the songs on his EP also date back to the pandemic, when people everywhere were stuck at home with their thoughts.

Music fans would probably classify his style as alt-country, he said, but “hipster country really hits it right where it’s at.”

Greene is putting the record out himself, with a lot of help along the way from some old friends in the music business.

The EP was produced by James Wallace, who heads up the Nashville, Tennessee, folk-rock band James Wallace & the Naked Light and performs so-called “cosmic country” under the alter ego of Skyway Man.

Greene said he and Wallace have been friends since kindergarten. “Just the luck of us both growing up in that same rural county in Virginia was really what set this off.”

Wallace also plays on Greene’s album, which they recorded at some of Skyway Man’s preferred studios in Nashville and Oakland, California.

Singing with Greene throughout is singer-songwriter Anna Nalick, who scored a Billboard hit in 2005 with the song “Breathe (2AM).”

Greene said he met Nalick while he was living in Los Angeles, and she is the one who convinced him to record an album.

“I don’t know if I would have done it without her encouragement,” he said.

She even came up with the title of the EP.

“That was Anna’s idea,” Greene said. “That was actually one of the conditions for her performing on this. She said, ‘I want to be part of this, but you have to call it ‘The Iceman Strummeth’. And I just said, ‘That is brilliant. We have to do that. You’re right.’”

Glaciologist Chad Greene poses next to an iceberg topped with penguins during his second field season in Antarctica in 2018.

Two Tucsonans also contributed to the record.

Greene commissioned collage artist Elana Bloom to create the album art featuring a man and a woman floating alone on separate icebergs in the same sea.

His first music video was made by Clinton Willis, a military veteran turned film student at the University of Arizona who Greene recruited after watching him win the monthly short film competition at The Loft Cinema.

They ended up shooting the video for “Harder to Leave” near Gates Pass, Benson and several other Southern Arizona locations. Greene hopes to premiere it at The Loft during First Friday Shorts on Feb. 2.

Glacial pace

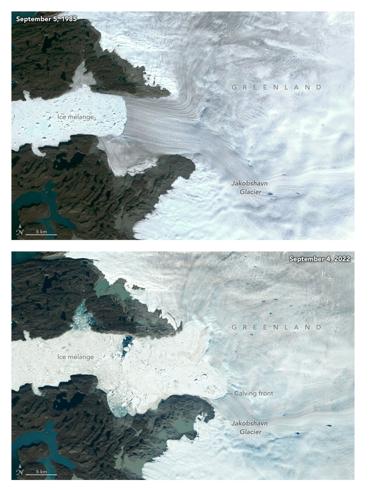

The Greenland glacier study took about three years to complete and involved analyzing almost a quarter of a million satellite images to produce a comprehensive, month-to-month look at more than 200 ice flows dating back almost 40 years.

Greene said a lot of the satellite images had to be manually digitized, which “usually meant having graduate students sit in a windowless office and click away on images to mark the edge of the glaciers.”

Eventually, specially designed computer algorithms were used to track the retreating glaciers in the images.

“Once we put it into one, clean, consistent dataset, the story really popped out,” Greene said. “It was like, ‘Oh my gosh, every glacier in Greenland is losing mass everywhere all at once’. It’s happening all over the island.”

And much of that melting began within the past two decades.

Greene said the Greenland Ice Sheet was relatively stable throughout the 20th century, with no dramatic changes. “Then something happened around the year 2000, where climate change really started taking hold,” he said. “We’ve seen this rapid decline ever since. It’s been steady and rapid and shows no signs of letting up.”

Satellite images from 1985, top, and 2022 show the retreat of the Jakobshavn Isbrae glacier on Greenland’s western coast. The glacier has lost an estimated 88 billion metric tons of ice.

Greene compared the loss of Greenland’s coastal glaciers to pulling the stopper from the drain of a massive bathtub filled with ice. If the entire ice sheet drained out into the ocean, it would raise sea levels around the world by about 24 feet.

So far, Greene said, global sea levels have not increased significantly as a result of the extra trillion metric tons of glacial melt that he and his fellow researchers identified in their study, because most of that ice was already deep underwater.

But the relatively rapid injection of so much freshwater into the Atlantic could alter ocean circulation and the distribution of heat energy around the globe, he said.

Of particular concern is Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (or AMOC for short), a flow system that moves as much water as 8,000 Mississippi Rivers and serves as a “conveyor belt of energy” between the tropics and the Arctic.

“It’s what dictates a lot of the weather in Europe. It’s why London doesn’t really get much snowfall, even though it’s farther north than northern Maine,” Greene said. “It can have really big effects on fisheries. It can have big effects on farming all over the world. And some models show that AMOC is highly sensitive to freshwater, like we could hit a tipping point where it shuts down.”

On the record

The debut single from “The Iceman Stummeth” — a stand-out, call-and-response number between Greene and Nalick called “The Refrain” — is set for release on Tuesday.

The second single, “Harder to Leave,” comes out Feb. 13.

The cover for the first album of music by Tucson-based glacier scientist Chad Greene.

He said he has no idea where this first foray into the music business will take him, but he’s “fascinated to find out.”

“I just want to explore things and learn,” Greene said. “That’s true in science, and it’s also true in art.”

If he ends up playing any shows to promote the album, he’ll have to work around his first trip to Greenland in March to study the ice there in person.

Ultimately, he just hopes someone out there will connect with his music the way he has with the songs that have inspired him.

“I have a real fondness for, like, Roger Miller and the old era of pithy, punny, sad country music. You definitely see those themes pop up on this album. There’s a lot of heartbreak, bleakness, not a great outlook,” Greene said.

Then he smiled.

“Actually, maybe I am starting to see some parallels with my work,” he said.

This long compilation of animations shows monthly changes to the edges of numerous glaciers in Greenland, based on satellite images captured from 1972 to 2022.