Just over a century ago, several hundred game fish raised in ponds in Iowa were hauled across the country by rail to be released into Arizona’s newly dammed Salt River.

A recent study suggests some of those transplanted buffalofish are still alive today in the waters of Apache Lake.

Not their descendants. Not members of the same species. The same individual fish that were sent west in 1918, as World War I was winding down in Europe during Woodrow Wilson’s second term as president.

Researchers identified seven buffalofish over the age of 100, including four so old that they were likely part of that original shipment to Roosevelt Lake, upstream from Apache, 105 years ago.

“There’s these hangers-on that have been there all this time,” said fisheries biologist Alec Lackmann, lead author of the study. “Apache Lake has sort of served as a sanctuary in the desert for these fish.”

An ichthyologist by training, Lackmann is an assistant professor in the Department of Mathematics and Statistics at the University of Minnesota Duluth.

He said buffalofish do not occur naturally in Arizona, but there are three species — bigmouth, smallmouth and black — that are native to the Mississippi and Hudson River systems in the U.S. and Canada.

Alec Lackmann, researcher from the University of Minnesota, Duluth, photographs the black spot pigmentation — age spots — on the pelvic fin of a buffalofish before it is released safely back into Apache Lake.

Lackmann described them as “gentle giants” that move through the water slowly, feeding on phytoplankton and tiny, freshwater crustaceans. The bigmouth variety is a freshwater filter-feeder, “the ecological equivalent of a whale shark” in the ocean, he said.

Until 2019, buffalofish were thought to live no more than about 25 years. Then Lackmann used a refined aging technique to document bigmouth buffaloes in Minnesota that were well over 100 years old.

He has since identified bigmouths in Saskatchewan that were born in the early 1890s and are still swimming around more than 125 years later.

Now, thanks to the research at Apache Lake, the smallmouth and black buffalofish also have been added to the world’s short list of animal species known to live past the age of 100.

Centenarian fish

“These fish are incredible,” said Stuart Black, a recreational fisherman who lives in Phoenix and co-authored the study. “We’ve got the only lake in the world with three species of centenarian fish.”

Black is the one who first tipped Lackmann off about the buffalofish in Apache Lake.

Apart from their remarkable longevity, the three species of buffalofish in Apache Lake also come in a range of colors.

He started fishing there in 2019, along with other self-described “conservation anglers” who go to great lengths to release the fish they catch without harming them.

They use less-damaging hooks with tiny micro barbs or no barbs at all and special nets and slings to properly support their catches without damaging their scales. Some even carry antiseptic ointment to treat any wounds they might find on the fish.

Almost right away, Black said, he began to notice distinctive black and orange spots on the usually ash brown or copper-colored buffalofish that he and others were catching at Apache. When he tried to find out more about the markings, his internet search turned up one of Lackmann’s earlier papers likening them to age spots.

Black said he sent the scientist an email with a few pictures and got a call from Lackmann less than 15 minutes later.

“He said, ‘These are the fish you are catching? I need to come down,’” Black said. “That started the whole project.”

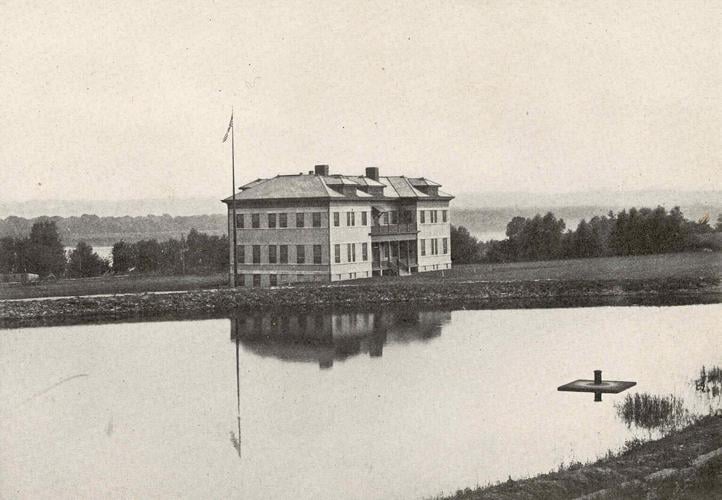

An image from 1916 shows the Fisheries Biological Station in Fairport, Iowa, the likely source of buffalofish that were introduced into Arizona's Roosevelt Lake in 1918 and are still alive today in Apache Lake downstream.

Lackmann and fellow researchers ended up making three trips from Minnesota to Arizona in 2021 and 2022 to study buffalofish that were pulled from Apache Lake by Black and his group of about 30 strict catch-and-release anglers.

Ironically, researchers had to kill some of the fish to figure out how old they were.

A total of 23 test subjects were aged using small stones of calcium carbonate called otoliths, which form in the inner ears of most fish species and can be dissected to reveal annual growth marks similar to the rings on trees.

“That was kind of hard for us,” Black said of sacrificing the old fish for science. “When you look back on it, you kind of cringe,” but it was the only way to know for sure.

The oldest individuals from each species turned out to be a 108-year-old black, a 105-year-old bigmouth and a 101-year-old smallmouth.

And such longevity appears to be a common trait in this type of fish.

Evidence detailed in the new study indicates that more than 90% of the buffalofish found in the Salt River reservoir, 160 miles north of Tucson, are at least 80 years old. Findings suggest that most of them probably hatched in the 1920s or earlier, including individuals brought to Arizona in 1918 that are “likely still alive as of 2023,” the study says.

The research was published last month in the journal Scientific Reports.

“Fountain of youth”

Lackmann said more study is needed to determine how many buffalofish might be living in Apache Lake and whether they have ever successfully spawned there.

To help with that effort, Black and his fellow conservation anglers have been collecting pictures of the buffaloes they catch there. The photo database now includes more than 220 “capture events” representing an estimated 180 individual fish, including ones that have been caught and released multiple times. One fish in particular has managed to get itself hauled out of the water six times so far.

Black’s 9-year-old son, Beckham, has been helping with the work, resulting in photos of the boy holding roughly 20-pound fish that are 10 times older than him. “It’s insane to think about,” Black said.

Beckham Black, 9, prepares to release an Apache Lake buffalofish that is likely more than 10 times his own age.

Their community-science-based fishing group doesn’t have an official name, but it does have a mascot of sorts. Black dreamed up a character called Buffalo Gill while he was researching the history of the fish’s introduction to Roosevelt Lake. He said he’s already making plans for a children’s book and a screenplay about the not-so-fictional fish that ventured out West more than a century ago.

The scaly journey shows up in the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries’ annual report for 1918: 420 fingerlings, yearlings and adults, mostly likely reared at Iowa’s Fairport Biological Station along the Mississippi River, then transported by train to Globe and released into the state’s newest reservoir.

A commercial fishing industry eventually sprang up on Roosevelt, operating there from the 1930s until the 1960s.

It’s unclear how and exactly when the buffalofish made their way downstream to Apache Lake, but Black said the unique population that has taken hold there deserves to be protected.

Buffalofish are unregulated in Arizona, and there is no limit on how many of them anglers are allowed to catch, according to Curt Gill, statewide sportfish program manager for the Arizona Game and Fish Department.

Gill — yes, Gill — said the fish can be taken with a variety of methods, including rod and reel, crossbow, spear gun, gig or snare.

That’s what Black is afraid of. Though buffalofish are difficult to catch with a line and hook, he said bowhunters can take them with relative ease.

Gill said state wildlife officials or interested members of the public could seek protections for the buffaloes in Apache Lake through the Arizona Game and Fish Commission, but the soonest any such regulatory changes might take effect is Jan. 1, 2025.

A close-up image shows black and orange spots on the tail of an Apache Lake buffalofish. Researchers have found that the long-lived fish only begin to exhibit such markings around the age of 40.

Black isn’t sure Arizona’s century-old trophy fish can wait that long. “Game and Fish wants to look at it in a year. I need it looked into as soon as this (story) hits,” he said.

Lackmann said the Apache Lake community of buffalofish will only “become even more interesting” as time goes on. Studying them could even improve our understanding of the aging process for all vertebrates, humans included.

“What is the fountain of youth for buffalofish?” Lackmann said. “We have a lot to learn from these fascinating fish.”

Longfin dace are swimming in Tucson's Santa Cruz River again after being gone for more than 100 years.