Last October, National Park Service ecologist Andy Hubbard hiked into an empty canyon on the east side of Saguaro National Park to collect water samples from Madrona Pools.

There was just one problem: One of the two spring-fed pools he was there to sample was completely empty.

“This usually has a whole springbrook that’s just dumping water in here,” said Hubbard, as his boots crunched on a dry pile of coarse sediment. “Holy cow.”

This is what another year of unusually hot, dry weather looks like on the western slope of the Rincon Mountains. It’s something that might happen more and more, scientists warn, as human-caused climate change continues to heat the planet.

In fact, the trend appears to be well underway.

Last year marked the 25th in a row with above-average temperatures in Tucson. According to the National Weather Service, 2023 finished in a tie for third on the list of the warmest years on record. Only 2017 and 2020 saw higher annual average temperatures over the past 129 years.

Nine of the 10 warmest years on record in Tucson have come since 2009.

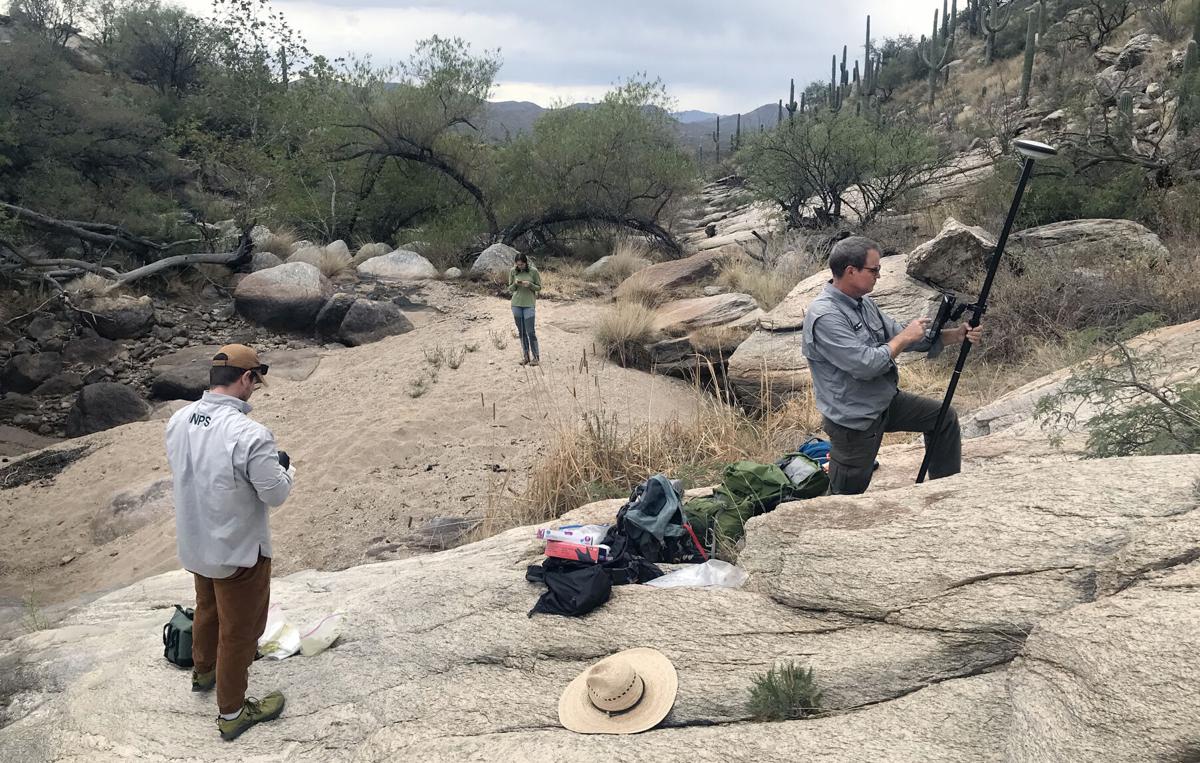

Hubbard is program manager for the park service’s Sonoran Desert Network, a team of scientists that collects and analyzes ecological data from 11 national park sites in the Southwest.

As part of that effort, he and his fellow ecologists conduct annual surveys of springs and wetlands from Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument in Arizona to Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument in New Mexico.

What they saw in Saguaro National Park last year was not promising.

Of the 21 perennial springs they routinely check there each September and October, five were completely dry and six others were down at least 80% from the flows recorded since 2017.

“Most of the sites we went to (last) year were much lower than expected,” he said. “Some sites were at least as dry or drier than they were in 2020,” which ranked as the single driest year — and the second driest monsoon season — ever recorded in Tucson.

Dry to the east

At a spot called the Grotto last fall, Hubbard said, they found the lower pool reduced to about 1/20th of its normal size and the upper pool completely empty for the first time on record.

Then there was the spring-fed brook in Joaquin Canyon, on the north side of the Rincons. Most years, Hubbard said, it flows along for at least a third of a mile, but in 2023 the output from the spring only made it a “pitiful” 12 yards or so.

“That one really shocked me,” he said. “That’s the stuff you see in June; this was in September.”

The Old Pueblo received slightly below-average rainfall in 2023, thanks largely to a mediocre monsoon that delivered almost an inch less rain than usual to the official weather station at Tucson International Airport.

Little Wildhorse Tank in the Rincon Mountains was little more than a puddle in October 2023.

But conditions were worse on the east side of Saguaro National Park.

“It was a long, hot dry season,” said Don Swann, a long-time biologist at the park. “There was very little rain in the Rincon Mountains.”

The Pima County Regional Flood Control District gauges on Rincon Creek and Tanque Verde Creek, near the park boundary at the east edge of Tucson, recorded less than 2 inches of monsoon rain.

Meanwhile, on top of the mountain, Manning Camp saw less than 6 inches of rain between June and October, “which is really low,” Swann said. Usually, that weather station will get 10 inches in July and August alone.

“I’ve worked here 31 years,” Swann said. “This was the driest I’ve ever seen the springs and streams” with the exception of 2020.

One of the worst spots he saw last year was Wildhorse Pools, a popular destination for hikers who pick up the trail at the end of Speedway.

Little Wildhorse Tank in the Rincon Mountains was little more than a puddle in October 2023.

“We had pretty good flow there last winter, but those pools were just really dry by the end of September,” Swann said.

Slowing the flow

Hubbard said the hot, dry conditions last year even seemed to affect the behavior of animals in the Rincons.

Usually wildlife scatters when his team approaches a spring to collect samples, but at one site high in the mountains, the white-tailed deer lingered not too far away from them as they worked.

“They were clearly trying to come in and use the water,” Hubbard said.

It’s nothing he’s ready to publish in a scientific journal just yet, but Hubbard strongly suspects what he and his team documented last year was the cumulative effects of extended drought and rising temperatures on spring systems that now need more than just one or two wet years to bounce back.

“This summer was not as dry as 2020, but the springs were at least as much affected,” he said. “A couple of super wet years haven’t made a whole lot of difference in the larger trajectory.”

Simply put, many of the springs in the Rincons and the wildlife they support are reeling, and the recent “climate whiplash” — record dry conditions one year (2020) followed by near-record rainfall the next (2021) — isn’t helping matters.

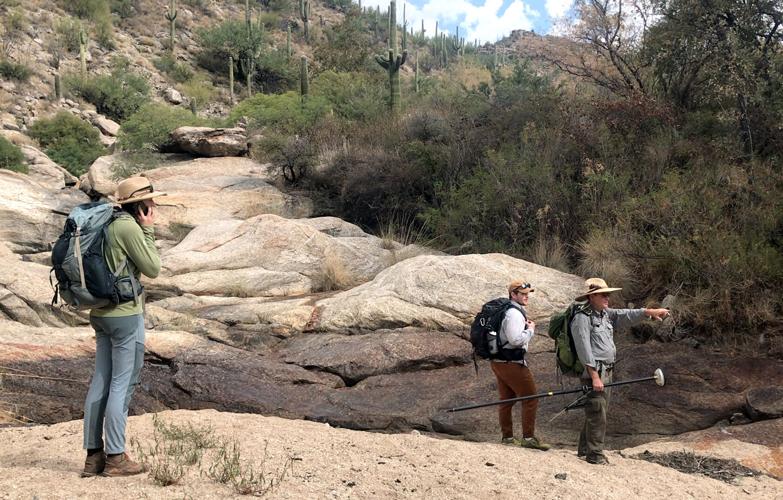

National Park Service ecologist Andy Hubbard, right, points to where the water should be in an unexpectedly dry spring pool in the Rincon Mountains on Oct. 17, 2023. Also pictured are fellow researchers Naomi Oberg, left, and Tommy Atella.

Hubbard declined to even speculate about what specific role global carbon emissions might be playing in what’s happening. He said that’s for other researchers to figure out using something called “attribution science” to tease out any clear signals of climate change there might be.

Whatever the cause, the park’s namesake cactus is showing the strain.

Swann said researchers have charted a decline in the survival of young saguaros throughout the park since the early 1990s that seems to coincide with an ongoing long-term drought in the region.

Such sharp drops in reproduction have been observed during previous extended dry spells, he said, so he isn’t overly concerned by the current trend.

He worries more about some of the rare, moisture-loving plants high in the Rincons. Surprisingly enough, he said, the top of the range is home to several different kinds of ferns and orchids. If conditions continue to get hotter and drier, those plants could be in trouble, because there is no higher place left for them to escape to on their sky island.

The long view

Meanwhile, two of the highest elevation water sources in the Rincons, Deer Head Spring and Spud Rock Spring, have “become less reliable over time,” Swann said, though the exact cause is unclear. He said it could be because the outflows are no longer cleaned out and maintained as they were historically, so plants now clog the manmade basins and suck up more of the water.

“At one time, both flowed pretty well, but they don’t flow so well anymore,” Swann said.

Other springs in the Rincons seem largely unaffected by the recent string of dry spells and record heat.

Hubbard thinks the ones that show little to no change from year to year are at least partially supplied by winter snowmelt stored up over multiple seasons. They might even flow with so-called fossil groundwater, rising up through cracks in the bedrock after centuries down below.

He said future research is planned to determine the approximate age and mixture of that source water by analyzing isotopes in the springs.

The Sonoran Desert Network is also busy screening water samples for traces of DNA that can be used to determine what amphibians and other wildlife are using the wetlands in the park.

Swann said he is grateful for the scientific work Hubbard and company have been doing at Saguaro. After all, the only way to truly know what’s happening to the desert’s precious water sources is by collecting long-term data on them.

“These high-elevation systems, and springs in particular, haven’t been studied a lot,” he said. “It’s very challenging to monitor water levels in these remote locations over time. I wish we’d started this a hundred years ago.”

As for Madrona Pools, Swann offered a first-hand report from his own visit on New Year’s Eve, when he helped dig out invasive buffelgrass in the canyon with a group of volunteers.

He said there was a small but promising amount of water flowing between the lower pools that day, a significant improvement over what Hubbard recorded less than three months earlier.

“It is recovering,” Swann said. “Hopefully we’ll continue to get rain this winter.”