Arizona’s Medicaid program is working with three insurers to create a long-term-care workforce to address the expected shortage of in-home caregivers needed as the state’s elderly population rapidly increases in coming years.

The insurers the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System, or AHCCCS, contracted with are Mercy Care, Banner-University Family Care and United Healthcare Community Plan. These insurers are contracted to build a long-term-care workforce within its AHCCCS network by 2024. Also working on the initiative is the Department of Economic Security’s Division of Developmental Disabilities.

The goal is “to ensure that Arizona is prepared to meet the projected need for licensed and unlicensed” caregivers in the coming decades, said Heidi Capriotti, an AHCCCS spokeswoman. This includes initiatives such as supporting innovative high school-based technical education programs that prepare graduating seniors to enter the long-term-care workforce, she said.

The insurers will provide services to more than 26,000 AHCCCS members who are 65 and older, blind, or disabled and at risk of institutionalization, according to state officials.

Capriotti said officials are also supporting legislation that deals with the training and testing of direct-care workers and assisted-living caregivers to help increase career mobility and decrease training and hiring costs.

One of those insurance plans in Pima County is Mercy Care, which has committed $2 million statewide to recruit, train, hire and retain between 6,000 to 10,000 new direct-care workers by 2022. These workers would be employed to deliver services to Arizona Long Term Care System clients under AHCCCS, said Sarah Hauck, Mercy Care workforce development administrator.

“We’re aware that there are about 1½ million adults ages 60 and older living in Arizona, and that many of these individuals, and persons living with disabilities, are supported by informal caregivers,” said Hauck.

“We know that Arizona’s population aged 60 and older is projected to grow more rapidly than any other in the state. And, in Arizona, experts expect a nearly 43% increase by 2025 of individuals 65 and older living with Alzheimer’s,” Hauck said. “It’s important to us that all of these individuals can live with dignity and as independently as possible. Our investment in developing the home-health workforce is part of that commitment.”

In Pima County, Mercy Care has contracted with United Way of Tucson and Southern Arizona, which will partner with Elder Alliance, a network of organizations supporting quality of life for seniors. United Way will work with PimaCare at Home to provide certified training to in-home and direct-care workers.

Other agencies in the Tucson-area awarded contracts by Mercy Care are All Valley Home Health Care, ResCare HomeCare, Southern Arizona Family Services and United Cerebral Palsy of Southern Arizona. These agencies also will work to recruit, train and improve their retention among direct-care workers they employ, said Hauck.

These caregivers — including personal-care aides and home-health aides — assist the elderly and physically disabled in their homes. Aides help with bathing, dressing, cooking, cleaning, laundry and running errands so that clients can remain safely in their homes rather than move to assisted living or nursing facilities.

The jobs can be difficult as many elderly patients suffer from illnesses or cognitive impairments, and the pay often tends to be around minimum wage, with no employee benefits. Employee turnover is generally high.

In Arizona, nearly 41,000 new jobs for direct-care workers are expected to open by 2026, and about 1.4 million nationwide because of the rising demand as the U.S. population grows older, said Stephen Campbell, a policy analyst for the Paraprofessional Healthcare Institute, a nonprofit based in New York City. The institute works to improve long-term services for the elderly and those with disabilities.

Arizona’s workforce development plan to recruit and retain direct-care workers “holds a lot of promise and added investment,” said Campbell, adding that Wisconsin is partnering with a nursing-home association to recruit and train certified nursing assistants, including offering a $500 retention fee after six months on the job.

In many families, adult children usually take care of their aging parents. But there are families who cannot because of their jobs or they live out of state or they need help because of their parents’ declining health. Then there are seniors who never had children or married.

That’s where the home-care worker comes to fill those needs. Their work is vital to senior citizens who want to remain in their homes as long as possible.

As the home-care industry, communities and government officials grapple with these realities, they also have to face the fact that the turnover rate of employees in the industry is high and must be remedied as Americans live longer, with 10,000 baby boomers turning 65 each day until 2030.

Among the main reasons home-care workers leave their jobs are low pay, part-time hours, shifting schedules and lack of benefits, industry experts say.

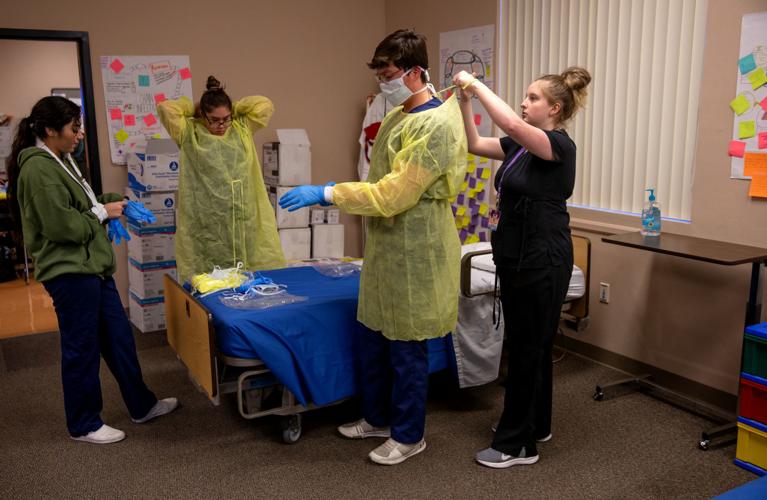

Oscar Beltran, 17, gets help putting on personal protective equipment from instructor Brittany Marcello at a Pima County Joint Technical Education District lab.

Many see work as a calling

Many of those who stay in the industry see the work as a calling and are passionate about it.

One of those is Brittany Marcello, 23, who is now an instructor for a high school career and technical education district known as Pima JTED, or Joint Technical Education District.

She explains that her grandmother was a nurse for five decades, mostly at St. Joseph’s Hospital, and her mother worked in admitting as a clerk, and now works at St. Mary’s Hospital in the imaging center. Her aunt also worked as a pharmacy technician at St. Joe’s and now works for a hospital in San Tan Valley.

“I was inspired by strong, attentive women who have been a driving force in my life,” Marcello said. “My grandparents helped raise me. I was 14 when my grandfather was diagnosed with esophageal cancer. I would stay with him overnight at the hospital. I liked being there for him and watching the nurses care for him,” she recalled.

“My nana was his primary caregiver at home. He was in hospice at home, and I helped with his care. This solidified for me how much I wanted to help people,” said Marcello. “Something happens inside of you. I decided health care would be a part of me.”

As a sophomore at Sahuaro High School, she enrolled in Pima JTED classes to become a certified nursing assistant and a certified caregiver who could work private duty or at assisted living and nursing homes. She did training at Tucson Medical Center and at The Forum, a senior community that offers assisted living, memory care for those with dementia, respite care and rehabilitation.

Once she was done with her studies and certifications, she began working full-time at TMC as a patient care technician on the neurology floor aiding patients who suffered strokes, traumatic brain injuries or underwent brain surgeries.

Four years ago, Marcello worked as a laboratory assistant at Pima JTED, enjoying “teaching students and instilling a love for health care.” Last August she became an instructor teaching health-care foundations, a mandatory class for juniors that introduces a range of health careers.

“As students, you have to want to be in the health-care industry, but as instructors you can pass on your love for the field and show students the possibility of growth.

“You have to be passionate about caring for people and dedicated and compassionate,” said Marcello. “One day you will need care, and you want someone who cares.”

PimaCare at Home provides caregiver training at the Katie Dusenberry Healthy Aging Center, 600 S. Country Club Road. Above are Mariana Millett (in blue) and Athena Bellmann.

Low wages are common complaint

There is no doubt that certified in-home and direct-care workers struggle with earning low pay, said Beth Francis, health-care professions manager for Pima JTED. She said the statewide initiative must look at wages and seriously consider sources to supplement pay for certified home-care workers who look after seniors and those with disabilities.

She said 93% of students who go through the program are college bound with goals to become nurses. Now it is common for colleges and universities to require students to have certified nursing assistant experience before they apply into its nursing programs.

Pima JTED students do well in nursing schools because they have the background and experience through its CNA program. For some students, financial hardships keep them from pursuing nursing careers and they remain working as caregivers for elderly, and some do quite well earning multiple training certifications.

“They want a little bit of everything to be challenged and to be excited about their work life. While they do their clinicals and internships, they blossom and their growth and maturity is just amazing,” said Francis, making reference to Marcello and other former students who are now teaching for Pima JTED.

More than 550 students have enrolled in health-care fields in the high school program, and 120 are expected to graduate in May. The district has campuses on Tucson’s east side and north side, and in July is scheduled to open a third campus near Interstate 10 and South Park Avenue.

Pima JTED works with Pima Community College, which serves as a pathway for students in nursing and other health-care professions.

Joseph Gaw, dean of critical care and nursing administrator for PCC, said nursing assistant courses have increased their capacity from 2016 to the present by 228%.

Administrators are finalizing a caregiver training course for possibly the summer as well as a certified medication assistant course for the fall semester. “These two training options allow for rapid entry opportunities for students to quickly train, become licensed or certified, and receive employment in a short timeframe,” said Gaw.

He said students eventually continue on to the licensed practical nurse program and other advanced studies for jobs in the health-care industry.

“We are finding that Arizona definitely recognizes the health-care industry as a key workforce concern and has worked to develop various task forces and think groups to address this issue. Health-care organizations are looking at different ways to recruit and retain employees in their organization as the turnover is often high in some areas of the health-care sector.

Cheyanne Yamez, 16, and Byanca Peralta, 16, check the temperature of fellow classmate Chloe Thompson, 16, at Pima County JTED’s personal assistant/caregiver lab.

Worker certification

In 1981 Judy Clinco, a registered nurse, founded Catalina In-Home Services — a home-care agency — when her mother needed support to remain in her home.

As an advocate for clients and caregivers, she also founded CareGiver Training Institute in 2001 for caregivers working in home care, assisted living facilities and nursing homes.

Almost 3,000 certified nursing assistants are graduates of the 198-hour dual certification program and have gone on to work in hospitals, nursing homes, assisted living communities, hospice, rehabilitation centers and in-home care.

Once a student completes the program, they take an exam through the Arizona State Board of Nursing, as required by certified programs, and if they pass they are qualified to be caregivers in the state. The state board requires 120 hours of state-approved training, but Clinco said the institute requires more.

“We feel the more knowledge they have, the more skills they are able to develop. This builds confidence and the more competency they have will lead to more success on the job,” explained Clinco.

Last year, the institute graduated nearly 190 students. “There is a tremendous demand and the institute recruits potential applicants who are screened before they go into training. In order to get state-certified, a background and fingerprint check is required,” said Clinco, adding the institute offers mentoring and support during the program.

Also among agencies that offer state-certified training for professional caregivers, and training for family members who care for loved ones at home, is PimaCare at Home.

The agency is locally owned as part of Pima Council on Aging, and state-certified direct-care-worker training will be offered within the Katie Dusenberry Healthy Aging Center.

Yadira Mosqueira, PimaCare at Home program director, said the training center has been designed for entry-level direct care workers, and for family caregivers who need to learn nonmedical in-home care skills.

More than 350 caregivers are expected to receive training over three years. These students will receive their direct-care-worker certification upon completion.

The center will offer additional skills training on top of the 20 hours required by the state for entry-level direct-care workers, said Mosqueira.

Applicants will be recruited from rural areas in Pima County and within the Tucson area, said Mosqueira, adding that agencies are partnering in marketing and recruiting efforts under the state’s workforce development plan that Mercy Care is funding in Pima County.