In 1964, a group of Tucson boys gathered in the basement of the old All Saints Catholic Church on South Sixth Avenue to be part of a new youth group. Most were in high school but a couple of them were younger. They signed up, with their parents’ enthusiastic endorsement, to form a mariachi ensemble.

The group of seven boys was christened Los Changuitos Feos, the Ugly Little Monkeys. Nearly all the boys had heard the rhythms that their elders listened to on the radio, but they hadn’t performed mariachi music.

Los Changos was the first of its kind. However, it was unique for another reason: an Irish priest from upstate New York led and taught the boys. Before he put on the white clerical collar, Father Charles Rourke was a jazz pianist. Assigned to All Saints, the charismatic priest wanted to minister to the boys through music and their Mexican culture. By all accounts he was masterful in turning the boys into precise musicians.

That was the beginning of Los Changuitos Feos, which burst out as a local sensation. The group attracted new members and within a few short years, it was performing sones, huapangos and rancheras to its growing numbers of admirers in Tucson and in major U.S. and Mexican cities: Washington, D.C., Chicago, Los Angeles, Mexico City and in Guadalajara, the birthplace of mariachi music. The boys performed before U.S. and Mexican presidents, on national television, and auditioned for the Ed Sullivan Show and for Herb Alpert of Tijuana Brass fame.

The huge success of Los Changuitos, which continues today, set the stage for the explosion of mariachi music in Tucson and across the country.

“We were the beginning of an entire movement, in education and musical genre,” said Dr. David Ruiz, who played the trumpet and joined the original seven Changos in 1964 when he was 13. His violin-playing younger brother, Mack Ruiz, joined soon after.

Yet behind the glowing facade of the group’s popularity lay a dark and ugly secret: Rourke was an alcoholic who stole money from the Changos’ performances, often left the boys alone while touring, and sexually preyed on the boys.

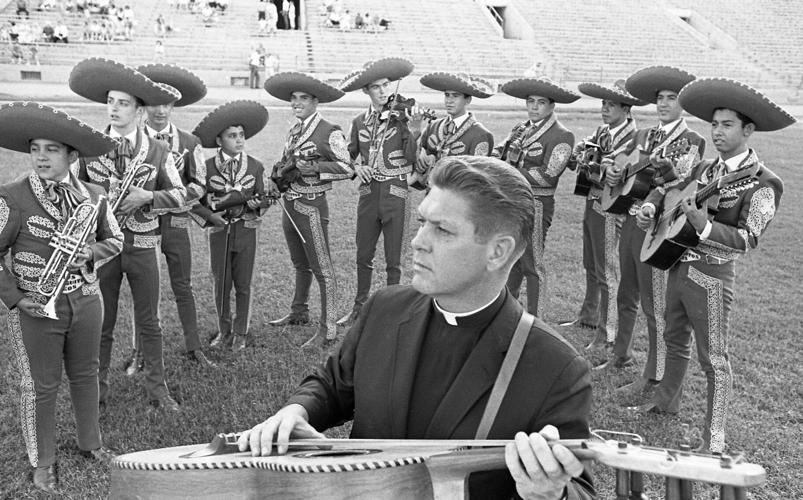

Father Charles Rourke and members of Los Changuitos Feos at University of Arizona stadium on July 4, 1966. Rourke was later dismissed from the group.

Despite the trauma and pain inflicted by Rourke during his five-year tenure, the boys persevered, focused on their music and performances, and coalesced, creating the foundation for mariachi youth groups for years to come.

“But if it weren’t for these kids who stuck together in spite of what took place, we wouldn’t be witnessing what we are today. Nobody seems to give them credit,” said David Valdez, a Tucson filmmaker who has focused his director’s lens on Los Changos and their valiant survival.

Valdez is completing a documentary, “Ugly Little Monkeys,” which he expects to release early next year. The film zeroes in on the group’s accomplishments and its unquestionable impact on the growth of mariachi music. Valdez wants to tell their heroic story of resiliency and dedication to one another.

“I wanted to hear their stories about the brotherhood they created, their experiences during that period of time when there were no chaperones, where they had to fend for themselves. If they were willing to talk about any experiences that they had personally with Father, it was up to them to share it,” said Valdez.

Speaking out

Several of the early Changos did open up in front of Valdez’s camera.

“All of us were victims, whether we were molested or not,” said Wilfred Arvizu, who joined Los Changuitos as a trumpet player in 1964 when he was 11 years old. He followed his older brother, Leonard Arvizu, into the group.

It was because of Wilfred Arvizu that Valdez decided to make his film.

In 2014, the year that Los Changos celebrated its 50th anniversary, Arvizu self published his account of Rourke’s depravity. “Bless Me Father For You Have Sinned” was the first public account of Rourke’s sexual attacks on some of the boys, who are unnamed in the book. Arvizu unveiled what had been whispered about Rourke, who was removed from the group in 1969. Rourke was transferred several times to parishes in and out of Tucson. In New Mexico he was under investigation for molesting a minor. In 1993, Rourke committed suicide.

“I read the book. That’s when I said there’s a documentary here to be told,” Valdez said. “He had the guts to write it from his experience.”

Filmmaker David Valdez is creating a documentary about Los Changuitos Feos de Tucson, also known as the Ugly Little Monkeys, a group of Mexican American kids he says became the first youth mariachi group in 1964.

Some of the boys confided in their parents about Rourke’s advances, his drunken stupors. But in a culture that looked up to Catholic priests and the Catholic church as infallible, some parents were in disbelief. Other parents, conflicted, became vigilant and began chaperoning the boys on some trips. And members of the board, which was formed to oversee the group’s finances, were unaware of Rourke’s pedophilia but knew of drinking problems. Valdez’s father was a board member along with this author’s father.

The boys themselves told new members about Rourke, cautioning them to never be alone with him. Their mantra became “dodge the priest.”

“We had our radar up,” said Randy Carrillo. He was 12 in 1966 when he joined. “Looking back, even to this day, there were definite terrible costs.”

Despite the warnings, some boys could not escape Rourke.

David Ruiz, who practices and teaches medicine in Washington state, said that Rourke’s “negative impact was felt by everyone in one way or another, some more than others.”

Arvizu, who remained in the group until 1971 when he graduated from Pueblo High School, wrote that Rourke “hit on” him and may have even done more one evening when Rourke drove him to his Pueblo Gardens’ home. Arvizu remembers escaping from the priest but that’s all. His memory has left him with “black outs.” The experience created problems for him later in life, excessive drinking and estrangement from his parents.

“I wanted to get the story out,” Arvizu said. “I felt a story like this shouldn’t be taken to the grave.”

A greater impact

While Valdez is not ignoring this aspect of the Los Changos’ story, the bigger story lies in the boys’ strength and determination in elevating mariachi music across the country. Before Los Changos, mariachi music was heard sporadically in Mexican communities in the U.S. southwest. After Los Changos, the musical and cultural landscapes changed.

Steve Carrillo

“I can’t over emphasize, now in retrospect, the impact of Los Changuitos Feos in mariachi history, not without cost,” said Carrillo, who along with his brother, Steve Carrillo, went on to successful professional careers with Mariachi Cobre.

From the Changos came Mariachi Cobre, formed in 1971 and still performing at the Epcot Center in Disney World, followed by the Tucson International Mariachi Conference in 1983, which remains alive, followed by Linda Ronstadt’s seminal “Canciones de Mi Padre” album in 1987, which remains the biggest selling non-English recording in the U.S. Moreover, countless numbers of school- and college-based and community mariachi groups grew from the seeds planted by Los Changuitos. For the documentary, Valdez scored interviews with Ronstadt and Louie Perez of Los Lobos.

Daniel Buckley, a Tucson historian of mariachi groups, called Los Changos “the Johnny Appleseed of the mariachi movement.”

Board member Alex Garcia, Jr., center, keeps rhythm while Esteban Dagnino, 16, left, and Julian Romero, 16, right, practice with members of Los Changuitos Feos mariachi group in 2014 in Tucson.

“The changes are so important on so many levels,” said Buckley, who is finishing his own documentary and book, “The Mariachi Miracle,” which takes a wider view of the development of mariachi music and folkloric dance in the U.S.

A turning point for the Changos came before Rourke was dismissed for stealing money. A board of directors was created to manage the group’s finances. Valdez’s father, Joel Valdez, who later served as the Tucson city manager and senior vice president of business affairs for the University of Arizona, led the effort to create a college scholarship fund for Los Changos. The college fund paved the way for numerous Changuitos to move into professional fields. The fund became a model for other groups to follow.

It was David Valdez’s relationship with the early Changos that gave him the entry to make the documentary. They knew him. They trusted him.

“I am very close to this. However, as a true filmmaker, sometimes those instances are uncomfortable and have to be told. On the other hand this doc is not about sexual abuse,” Valdez said.

He graduated from Cholla High School and studied cinema at the UA. Later he earned a master’s in fine arts (cinematography) from the American Film Institute. He has worked for more than 30 years in the motion picture and television industry.

Violinist Victoria Arias, right, performs with the mariachi group Los Changuitos Feos in Sabino Creek during the Special Olympics El Tour de Tucson bicycle race on Nov. 22, 2014. Decades after a tumultuous time, the group continues to forge a musical path.

This will be Valdez’s most personal project. It’s likely to be received with some resistance from people who would prefer not to delve into the Changos’ past. Some people may even fear the public revelations of Rourke will harm today’s current and future Changos. But Valdez, as do the Changos whom he interviewed, believe otherwise.

“The true story of this documentary is the triumphant story of what these original kids started and where the mariachi movement is today,” Valdez said. “That is the story.”

Photos: Los Changuitos Feos, Tucson's first youth mariachi group

Los Changuitos Feos

Updated

Father Rourke and members of Los Changuitos Feos at University of Arizona stadium on July 4, 1966.

Los Changuitos Feos

Updated

Trumpeter Jeff Nevin performs with Los Changuitos Feos during a Christmas concert for residents of the Marshall Home for Men on Dec. 21, 1985.

Los Changuitos Feos

Updated

Fernie Sanchez, far left, and members of Los Changuitos Feos on May 8, 1974, prior to a 10th anniversary concert at TCC.

Los Changuitos Feos

Updated

Father R. John Martin, with cross, listens to Father Rourke and members of Los Changuitos Feos at St. John's Catholic Church in Tucson on May 19, 1969.

Los Changuitos Feos

Updated

Los Changuitos Feos performs from the back of a stake bed truck at Southgate Shopping Center, Sixth Avenue and Interstate-10, on Dec. 9, 1977.

Los Changuitos Feos

Updated

Belinda Garcia of Los Changuitos Feos solos during practice on Jan. 20, 1997.

Los Changuitos Feos

Updated

Board member Alex Garcia keeps rhythm with Julian Romero, 16, left, while guitarron player Christian Salgado, 15, practices with members of Los Changuitos Feos. Garcia is the point person for bookings.

Los Changuitos Feos

Updated

Andrea Guzman, 15, plays a song on her violin while members of Los Changuitos Feos mariachi group practice.

Los Changuitos Feos

Updated

Ali Pizarro, 17, lets loose his vocals during a song while members of Los Changuitos Feos mariachi group practice on Wednesday, Aug. 13, 2014.

Los Changuitos Feos

Updated

Abigail Arias, 15, plays with other violinists while members of Los Changuitos Feos mariachi group practice on Wednesday, Aug. 13, 2014

Los Changuitos Feos

Updated

Abigail Arias, 15, practices her violin while members of Los Changuitos Feos mariachi group practice on Wednesday, Aug. 13, 2014

Los Changuitos Feos

Updated

Musical director Salvador Gallegos, right, works with guitarron player Christian Salgado, 15, on a song while members of Los Changuitos Feos mariachi group practice on Wednesday, Aug. 13, 2014

Los Changuitos Feos

Updated

Trumpet players Isaiah Garcia, 16, left, and Ricardo Vejar, 17, practice with the other members of Los Changuitos Feos mariachi group practice on Wednesday, Aug. 13, 2014

Los Changuitos Feos

Updated

Violinist Yvette Lanz, 16, practices with the other violinists of Los Changuitos Feos mariachi group practice on Wednesday, Aug. 13, 2014

Los Changuitos Feos

Updated

Dominic Bourland and the rest of Los Changuitos Feos serenade the audience as they cross the lobby to their seats before the Homenaje: La Vida de Lalo Guerrero, a tribute to Eduardo “Lalo” Guerrero at the Fox Theatre in 2006.

Los Changuitos Feos

Updated

Lesly Moran leans into her violin as she and Los Changuitos Feos mariachi group plays for the crowd for the Cinco de Mayo Weekend Fiesta at Pinnacle Peak and Trail Dust Town in May, 2014.

Los Changuitos Feos

Updated

Los Changuitos Feos de Tucsón

Así lucen Los Changuitos Feos de ahora.