Thursday, April 4, 1968

It was a Thursday evening performance, just a few days before “I’m Solomon” was to close in Baltimore and head to Broadway. It had been, as always on a pre-Broadway tour, a long day … rehearsals to make changes based on the previous night’s performance and audience reactions, back to the hotel to rest, then back to the theater for our evening performance.

When the curtain came down on Act I, the cast headed to our dressing rooms to rest … and prepare for Act II. But that evening the entire cast was asked to come to the rehearsal room for a cast meeting, something highly unusual in the middle of a performance.

One of the producers stepped forward and told us quietly that Martin Luther King Jr. had just been murdered in Memphis. Stunned silence for a moment, but the cries that followed were from our guts.

Ours was an unusual cast for the 1960s — very racially diverse. A large portion of our cast were African American, so the pain any cast would feel was amplified by the make-up of our “family.”

After a moment, the producer spoke again to tell us that, after considerable thought, their team had decided we would finish the show. Now, you must remember, this was in 1968, long before cell phones and ubiquitous media access. Audience members would be in the theater’s lounge having a drink, or on the sidewalk smoking a cigarette. They would not hear the news.

We were told to go to our dressing rooms and get ready for Act II.

“The show must go on.” That old Broadway adage became our reality at the Mechanic Theatre that evening. We were in shock, individually and collectively, but we were expected to touch up our make-up and get ready to sing and dance and smile and complete the show, happy ending and all. So, we did.

The strain of that second act was palpable. Knowing glances between dancers. Songs taking on different meanings with the knowledge we held, but still unknown to the audience. “With Your Hand in My Hand,” an upbeat song of hope and love conquering all. A final reprise. Happy ending. Curtain. Applause.

But instead of the curtain rising again to take our bows, the producer walked out from the wings to tell the audience what had happened. Gasps and cries from our audience — people who had just been given a message of hope and love and togetherness. He gave them the few details that were known, thanked them for coming and asked them to drive home safely.

That evening, I think Baltimore was in shock as much as we all were. Haunting quiet as we walked back to our hotel from the theater. I spent that night glued to the news.

Friday, April 5th, 1968

There was some comfort in returning to our routine: rehearsals during the day to make adjustments based on last night’s show. During breaks, painful conversations about what Martin had meant to each of us. His words and leadership so reassuring and visionary, giving hope that one day we would all reach that mountain top.

For me, recollections of civil rights marches I’d attended as a child, brought there by my parents. Confederate flags flying and other students jeering along the routes of civil rights marches in Bloomington, Indiana, when I was in college. My dear friend Altovise, who was Black, telling me that perhaps I should look for an apartment alone, since somehow every apartment we looked at in New York when we decided to become roommates was taken by the time we got there at 8 a.m. on a Sunday … because of her race, an awareness that surprised me, but was part of her daily life.

The show went on … again.

Saturday, April 6, 1968

Matinee: Unrest was beginning to stir in Baltimore. Police officers were everywhere. The waitress at the lunch counter we went to before the show somehow never coming to serve this mixed group of performers ready to order — until we made a fuss.

As I walked back to the hotel between shows with a couple of other dancers, I was frightened when two police officers, one with a K-9, started following us. Their conversation, clearly taking place for our benefit, was threatening. They didn’t much like mixed groups. Fortunately, we were just a block from the hotel, so we were able to quickly duck into the lobby.

Evening performance: Things were still relatively quiet in Baltimore when we arrived at the theater for the final performance of “I’m Solomon.” We were all exhausted, both physically and emotionally. At intermission, we were once again summoned to the rehearsal room for a cast meeting.

This time the show would not go on. Rioting was breaking out all over Baltimore, including neighborhoods not far from the theater. We were told to pack up our dressing rooms and get back to the hotel quickly, walking in groups. While we did that, the producer stepped out in front of the curtain as soon as the audience was seated for Act II and told them what he’d told us. Riots were getting too close. Your ticket costs will be refunded. Please get to your cars quickly and drive home safely.

Back at the hotel, I joined a friend for drinks at a bar there with a panoramic view of the city. We watched in horror as fires popped up spontaneously all over the city.

Sunday, April 7, 1968

We boarded buses early Sunday morning for the ride back to New York City. The shockwaves and pain caused by Dr. King’s assassination were unavoidable as we drove through neighborhoods that looked like war zones. The homes and communities of the people Martin most wanted to lift up had been razed.

The day Martin was killed remains etched in my heart.

“I’m Solomon” opened on Broadway a couple of weeks later but lasted only a few days. The memories remain part of my life.

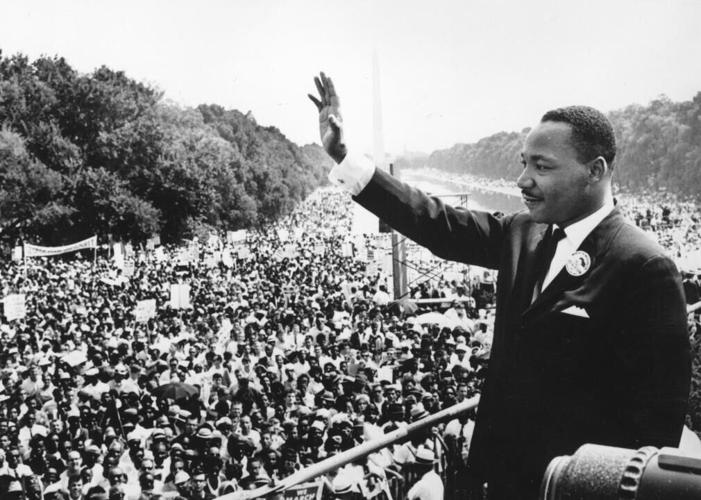

April 4, 1968. King was shot and killed as he stood on the second-floor balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, TN. The “apostle of nonviolence” had gone to Memphis in support of a sanitation workers' strike.