For many of us who call the borderlands our home, there is a reality to our lives and our history. We travel back and forth. We visit family south of the line and family comes here, even if the distance is measured in a few miles. Some families’ histories stretch back to before Spanish colonizers arrived, while others were born yesterday.

But for the vast majority of people who live far and wide outside the 2,000-mile long corridor — including many who do live within this region — their reality is defined by myths or in today’s lingo, alternative facts. For them the borderlands are unsafe, full of dangerous people and places. The border sucks in valuable resources while failing to contribute to the general good. The border region has no past but a nefarious present and a dark future.

Sadly it’s the myths, not the reality, that lead policymakers and governments, at all levels, to remake the border.

Myth makers have long recreated the border into their alternative reality. Oddly enough yesterday’s manipulators didn’t paint the borderlands as a place to stay away from, rather they pictured the borderlands as an inviting, idyllic place to visit for leisure, for improved health and for better opportunities. It was a place with lots of sunshine and lovely señoritas, and an entryway to “old, romantic” Mexico.

At the University of Arizona Special Collections Library, an exhibit called “Visions of the Borderlands: Myths and Realities,” curated by Verónica Reyes-Escudero and Bob Díaz, takes the visitor back to the late 1800s, when the border myths began to be spun for outsiders, and into the first half of the 1900s when the myths, some drawn from bits of distorted reality, became part of the popular culture through the prolific use of picture postcards, Western films and books, and tourism promotion by institutions like the Tucson Chamber of Commerce and the Tucson Sunshine Climate Club, and dude ranches and sanitariums.

These images and messages spread the appeal of a mythical land crowned by mountains, adorned by lush desert and populated with smiling, happy people in quaint towns like Tucson. Movies and books romanticized the land and the tough settlers, waxing over their adventures and accomplishments. And it got better during the Prohibition period when word went out that just across the border, visitors could find liquor and freedom.

Civic and commercial boosterism knew no bounds.

“The free out-of-doors life brings everyone together and within a short time the man from the most distant spot finds himself as much at home as the native, and when you stop to think that the majority of the so-called ‘natives’ were born ‘back east’ it can readily be understood why the tastes of the Tucsonians and the tourists are always on the same plane,” trumpeted a 1920s Tucson Chamber of Commerce publication, “Where to Spend the Winter,” one of the many items in the exhibit.

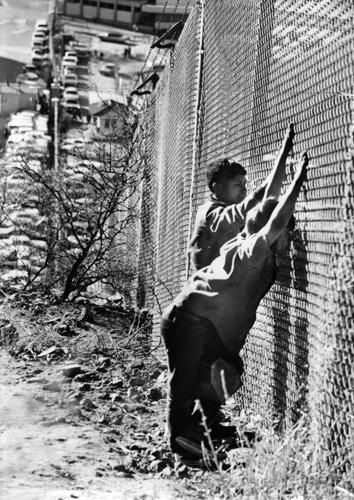

The reality behind those myths was that there were long established communities, on both sides of the border, that built the towns, herded the cattle, mined the ore, harvested the crops. The Mexican-American, Chinese, indigenous and black residents were virtually nonexistent in the mythical narrative.

When they did appear, they took shape as outliers, marauders, thieves, submissive servants. And when needed and necessary, the myth weavers assured nervous visitors that “savages” and “bandidos” in the lawless land would be eliminated by brave soldiers and sheriffs.

That same message is spread by the current myth creators: An expanded wall and border enforcement are needed. Refuse entry to refugees and immigrants, and pursue those already here. Threaten Mexico that U.S. soldiers will be sent to clean out the “bad hombres.” Label those who resist the mythology are labeled "un-American."

This is the vision of our borderlands that today’s peddlers are selling. The hucksters continue to sell Tucson and Southern Arizona as a myth.