A Tucson man who has spent 42 years behind bars in connection with the downtown Tucson Pioneer Hotel fire that killed 29 people is expected to be freed from prison Tuesday.

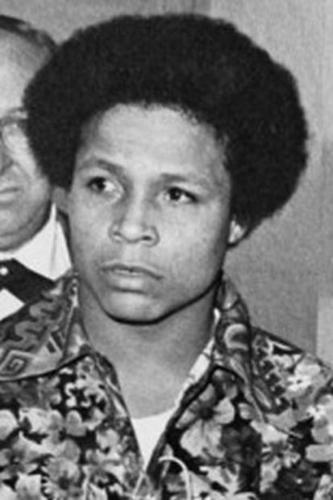

Louis Cuen Taylor, is scheduled to plead no contest as part of an agreement that sets aside his original conviction and gives him credit for time already served.

Taylor, who turns 59 this week, struggled with the decision to plead no contest.

"He initially rejected it," Arizona Justice Project Executive Co-director Katie Puzauskas said.

Taylor always has maintained his innocence. Even the judge in his 1972 trial publicly expressed skepticism about the jury's decision to convict the Tucson teen.

After saying he would not have convicted Taylor, Judge Charles L. Hardy publicly apologized for second-guessing the jury. "The jury had so much conflicting evidence that I just judged some of the evidence differently than they did," he told the Arizona Daily Star in March 1972.

For years after the trial the judge maintained a correspondence with Taylor, sending him law books and Christmas packages. In one letter he sent Taylor in the early 1980s, the judge, who died in December 2010, said he was negotiating with Arizona lawmakers to have the sentence commuted, but the deal was predicated on Taylor admitting guilt, which he refused to do.

The night of Dec. 19, 1970, more than 750 people were at the Pioneer Hotel at Stone Avenue and Pennington Street downtown. A Christmas party for Hughes Aircraft employees was in full swing, and many rooms were occupied by visitors from Sonora, Mexico, who were finishing their holiday shopping.

Just before midnight, a fire broke out on the fourth floor. Flames raced up through the 11-story building, which was billed in promotional pamphlets as "fire proof." The speed of the blaze left many guests trapped in their rooms. The building did not have a sprinkler system, and that, combined with exits locked to prevent theft and firetruck ladders too short to reach the higher floors, caused some - including children - to jump from windows to their deaths to escape the searing heat. Others burned to death in their rooms. Most died of carbon-monoxide poisoning while waiting for rescue. In total, 29 lives were lost to the blaze, including one victim who died months later in a hospital.

Taylor, then 16 and known to local police as a "delinquent," was in the hotel that night watching the festivities and trying to cadge free drinks. After the fire broke out, he and a hotel custodian tried to extinguish the blaze, then Taylor helped some of the trapped and injured guests escape. Hours later, early on the morning Dec. 20, he was taken into custody, interviewed by police without parental consent and charged with starting the fire. He was convicted in 1972 after a seven-week trial in Phoenix, and sentenced to 28 concurrent life terms.

Last October, attorneys with the Arizona Justice Project filed a motion for post-conviction relief, asking for the case to be dismissed or for an evidentiary hearing. The attorneys, including Michael Piccarreta of Tucson and former Arizona State Supreme Court Justice Stanley Feldman, said several defense experts, using modern forensic fire science, would testify they would not have ruled the blaze arson.

The defense team also alleged a prosecutor engaged in misconduct by not giving defense attorneys a laboratory report that said no accelerants were found and by talking to the judge without defense attorneys present.

More recently, an investigator with the Tucson Fire Department reviewed the available evidence in the case and was not able to determine what caused the blaze.

Deputy Pima County Attorney Rick Unklesbay said, however, the original fire investigator for the prosecution still believes the fire was purposely set, and the TFD investigator who recently reviewed the evidence did not have access to a great deal of evidence. Much of the evidence in the case was destroyed in the 1990s or disappeared after civil attorneys took possession of it when they sued the hotel.

And although defense experts said they could not determine the cause of the fire, that does not mean it was not arson, Unklesbay made clear in an interview last month. In addition to the prosecution's original fire investigator standing by his 42-year-old report, other evidence presented at the 1972 trial indicated the fire was arson.

Note: Reporter Kimberly Matas has been researching the Pioneer Hotel story for several years as part of an independent book project. Contact her at kmatas@azstarnet.com or at 573-4191.