Arizona Daily Star border reporter Danyelle Khmara speaks to people who hold a stake in the borderlands — who work, live, travel and migrate in the Arizona-Mexico border region or whose lives are affected by immigration and border policies.

In this occasional series, Khmara brings readers the voices and stories of those people to illuminate what life is really like on the border.

Give people a chance

“Trust is a heavier burden than discipline,” says Aaron Flores, at the small migrant shelter and help center in Sonoyta, Sonora, just across the international border from Lukeville, south of Ajo and Organ Pipe National Monument.

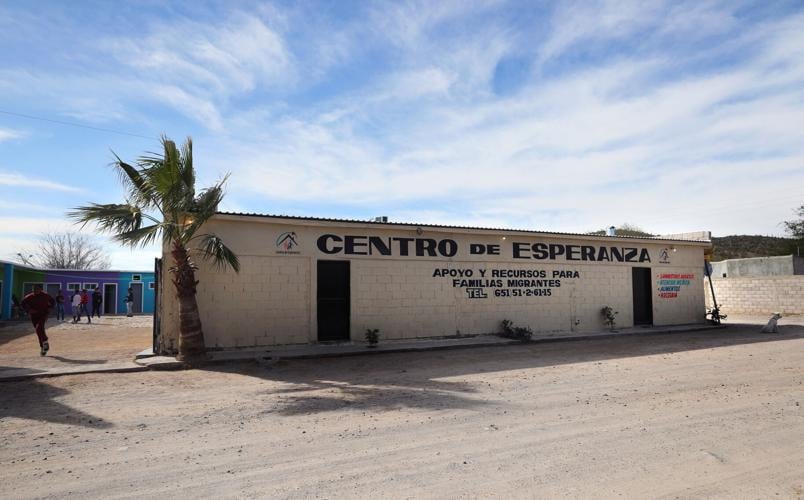

In his work at Centro de Esperanza, Flores and his co-manager Karla Betancourt work to restore autonomy to people often in a position where they have little control over their lives.

The center has rules. There is no smoking, drinking or cursing. People are expected to treat others with respect. But they give people as many choices as they can, Flores says.

“If you give people the chance to do whatever they want, usually they do the right thing,” he says.

‘A little bit of dignity’

Centro de Esperanza helps migrant families who are waiting on the Mexican side of the international border, hoping to apply for asylum in the United States.

They currently have space for 25 people to stay, and while stays vary, people typically stay one to eight months.

In addition, they help find affordable rentals for 150 to 200 migrants at any given time and offer them daily basic services, including access to WiFi and computers, food, showers, clothes, first aid and pro-bono legal help from Justice for Our Neighbors, an Arizona-based nonprofit.

Running a shelter with so many moving parts and an ever changing collection of faces, there needs to be some rules. But creating a community where people depend on each other can subvert the need for as many rules.

Take morning coffee, for example. It’s the most important time of day at the center, Flores says. One of the women staying at the shelter has volunteered for the job of making the coffee.

“That’s what we want to promote,” Flores says. “You don’t have to do stuff because we say so. You do it because it’s for the best.”

Not only does prioritizing trust and communal responsibility work to keep things running smoothly, but it partners with another of the center’s objectives: working to restore people’s autonomy and dignity.

They looked at how other shelters and centers provided basic services, such as food, clothing and hygiene products, and they wanted to add something meaningful, Flores says — variety.

When someone goes to the store to pick out shampoo, they might have considerations, Flores says, like whether their hair is frizzy or if they have dandruff. So when the shelter gets supplies like shampoo, they shoot for variety to give people choices.

They also let people choose their clothes. Two rooms full of donated clothes at the center are like free stores. People can look around and pick, which gives them some control over how they look.

“Basically, as an immigrant, you’ve got very little choices,” Flores says. “So what we try to give them, it’s the best we can for them to feel normal, like everyday normal people.”

In the Border Patrol’s Tucson Sector, which covers 262 border miles and stretches from New Mexico to Yuma County, agents apprehended more than 22,000 migrants in December, of which nearly 4,500 were in family units and more than 1,400 were unaccompanied minors.

The magnitude of these numbers makes it easy to forget they represent individual human beings, Flores says.

“Individual human beings, having different necessities, different sufferings,” he says. “What we try to do here is give back a little bit of that dignity and that sense of freedom.”

Aaron Flores, co-director, talks about the clothing donated at Centro de Esperanza, a migrant shelter in Sonoyta, Mexico. Migrants can pick out clothing for themselves for free.

Home

Flores was once a migrant himself, in the U.S., though the immigration landscape was very different.

He came to the states undocumented with his family in the late ’90s. Back then, Flores says, you could just walk across. He was a young father and wanted his son to have more opportunities.

At that time, unemployment was low and the U.S. was experiencing record immigration levels.

“There was so much work in Phoenix and in the United States in general that companies were fighting for workers,” Flores says.

After 11 years working and living in the U.S., he returned to Sonora. His son, now fully grown, still lives in the states and works as a chemist for a big company.

“He made it, and I accomplished what I wanted to accomplish,” Flores says. “Don’t get me wrong. I love the American way, and I miss it sometimes. But this is my home.”

Back in Mexico, Flores worked as a paramedic for the Red Cross for many years. He started working for Sonoyta Mayor Jose Ramos, then a political candidate, as an on-hand medic at political events.

After Ramos was elected, Flores, who was well connected to the community, began working for the town as director of arts and culture.

When he met Betancourt, who runs the center with him now, she was a city council member. They started planning community events together, events the town hadn’t seen before, like jazz shows and art and photography contests.

“We did a lot of things together. And it turned out we were a great team, because we’re so different,” he says. “We fight every day, but that makes us do things right because we see the flaws in each other’s plan and we can work it out, and the results come out pretty good.”

Centro de Esperanza, a migrant shelter in Sonoyta, Mexico.

‘Our biggest supporters’

More migrants had been showing up in Sonoyta, a city of about 20,000 people, and there weren’t any services for them. It made the community nervous, Flores says.

“The community in general had a really bad perception about immigrants,” he says.

Both he and Betancourt had limited experience working with migrants. She had done some volunteer work to help migrants in the area, bringing coffee, blankets and other basic stuff to immigrants who were scattered around town. And in his work as an EMT, Flores visited some shelters in Sonora, and Betancourt began coming along.

Flores first met people from Shelters For Hope, the Arizona-based nonprofit that runs the center, when they had a meeting with the mayor to talk about what they had planned for the shelter. Ramos asked Flores, being the only one around who was completely bilingual, if he would meet with them.

John Orlowski, cofounder of Centro de Esperanza along with Arlene Rivera Cortez, says the purpose of that meeting was to start bridging a gap between the migrants and the town, to help the community understand why so many new people were showing up.

If they had to pinpoint one accomplishment since the shelter opened, Flores says, it would be the way they’ve changed the town’s point of view about immigrants.

“When we started here, the neighborhood was really concerned about: What kind of people are you going to bring here?” he says. “But now, our biggest supporters are our neighbors.”

Asking for asylum

With a recent purchase of a one-and-a-half-acre adjacent property, Centro de Esperanza will expand from 25 to 150 beds.

While many shelters separate families, with men in one area and women and children in another, the center will allow families to stay together. They are currently fundraising for the expansion and hope to open it by the end of the year.

In the meantime, they continue to work with Justice for Our Neighbors to walk people through the process of building an asylum claim.

Not long ago, people would present themselves at a port of entry to ask for asylum. Both international and domestic laws say people fleeing certain types of persecution have this right. But U.S. policies like Remain in Mexico and Title 42 have largely obstructed that ability by expelling some migrants to Mexico regardless of whether they are asking for asylum.

Now migrants either cross between ports of entry, an often deadly journey, or they apply for asylum through one of the few Title 42 exemptions, which they can apply for through the Customs and Border Protection One app.

New migration policies, the first meaningful ones of President Joe Biden’s term, have allowed a few more migrants at Centro de Esperanza to have a chance to ask for asylum.

The center and their partners have helped 455 people through the asylum process, with support of the migrants’ sponsors in the U.S., usually friends or family member.

Despite all these challenges, in Flores’ estimation getting across the border is the easy part. What’s hard is making their case for asylum strong enough that they can stay, he says.

For every person they’ve helped get permission to enter the U.S. who has a good chance to win their asylum claim, another 20 will fail, he estimates.

“We have families here who come with a story, a really awful story,” Flores says. “Because we’re just a first step, we don’t ask them for proof. That’s what the lawyer’s job is. We need to believe everybody. We need to trust everybody, by being careful but being trusting.”

Migrants play around with a volleyball in the courtyard at Centro de Esperanza, a migrant shelter in Sonoyta, Mexico.

‘A part of this community’

Across the street from the center is a soccer field. There’s a citywide league and the center has a team. Anyone who’s there can play, and since the nature of the shelter is that people come and go, the team members are always changing. Nonetheless, they won their first three games.

But they’re not there to win, Flores says.

“That one hour that they play, you can see on their faces that the only thing that’s on their minds is playing the game,” he says. “They’re not thinking about the app or Title 42 or the harshness of being this far away from home.”

“You can see their families, that they’re cheering. They don’t care about anything else but the game. It’s just one hour, but it’s a disconnect, totally. They go back to their problems once it’s done. So we tried to create as many activities that help them keep their minds off the problems that they’re going through.”

The center also invites migrants to cultural and community events in town. They want them to feel like they are a part of the community, Flores says.

“They play, they interact with the people of the community. So they’re now seen not as outsiders but as a part of this community. They might not be here for a long time, but as long as they’re here, they are getting integrated.”

Haitians seeking to escape from poverty and uncertainty are flocking to the main migration office in the capital Port-au-Prince hoping to get a passport and perhaps their ticket to life in America under a new US immigration program. Under the policy announced by President Joe Biden, the United States will accept 30,000 people per month from Haiti and a handful of other countries mired in crisis, on the condition that they stay away from the overcrowded US border with Mexico and arrive by plane.