Think of five years worth of Tucson Water’s annual deliveries to 739,000 people.

That’s how much water, totaling about 500,000 acre-feet, that leaders of the three Colorado River Lower Basin states hope to soon find ways to save each year from the river’s dwindling supply, said Bill Hasencamp, a top Southern California water official.

The states, enmeshed in detailed, private negotiations with the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation since early summer, have set that as a target to keep Lake Mead from quickly falling to critically low levels, he said — levels that could jeopardize its ability to serve Tucson and the Southwest with drinking and irrigation supplies.

They hope to come up with a plan by December to achieve the savings, said Hasencamp, manager of Colorado River Resources for Southern California’s Metropolitan Water District. Along with California, the other states are Arizona and Nevada.

These discussions have taken on more importance since August, when one of the bureau’s most pessimistic forecasts predicted Mead could fall below 1,030 feet by summer 2023. Under a formal drought plan the three states approved in 2019, such negotiations are required when that forecast is made two years in advance.

Water flows into a canal that feeds farms run by Tempe Farming Co., in Casa Grande. Many experts say farms should be most heavily targeted for water cuts because they use about 70% of the Colorado River's water not lost to evaporation or other natural forces.

But meeting this target won’t be nearly enough to wipe out a “structural deficit” in the Lower Basin between use and supply of about 1.2 million acre-feet a year. It also pales compared to a 3.2 million acre-foot annual shortfall the bureau has predicted for the entire, seven-state river basin by 2060.

Gov. Doug Ducey took a step toward water savings last week. He announced Arizona would take $30 million out of unspent, federal COVID-19 relief money in the state’s coffers to compensate “one or more Colorado River users” to forego deliveries or diversions of river water supplies. The money will be used to create water savings in 2022 and 2023, said Shauna Evans, an Arizona Department of Water Resources spokeswoman. Any entity in Arizona receiving Colorado River water is eligible to participate.

But given recent, precipitous drops in reservoir levels — at least 45 feet at Lake Powell and 15 feet at Lake Mead in the past year — virtually everyone involved in the river issue agrees more dramatic actions are needed, soon.

“Getting real” about the river means acknowledging the basin is going through a long-term process of increasing aridity, not a cyclical drought, Arizona State University researcher Kathryn Sorensen recently told an water conference audience at the University of Colorado.

Farm workers harvest and package cauliflower on a farm near Yuma. Agriculture contributes nearly $3.4 billion in annual economic activity to Yuma County, the Yuma Agricultural Water Coalition said.

“On a long-term, sustained basis, the Lower Basin needs to cut by more than 500,000 acre-feet, and I don’t see how, politically, we can cut 3 million. That being said, if we get another year or two of terrible runoff, we may not have a choice,” she said.

But getting real also means “we all need to get off our high horses,” Sorensen added.

“Everyone. Me, you, everyone in the basin. Thinking that your water use is justified, and no one else’s is, is not helpful. Thinking that you know how water should be allocated and everyone else has it wrong, is not helpful. And it’s going to push us into camps at a time when we need to focus on collaboration.”

This advice will get its acid test when basin states must decide how much cutting should be borne by farms versus cities. Many experts say the farms should be most heavily targeted for cuts because they use about 70% of the river’s water not lost to evaporation or other natural forces.

But water researcher Brad Udall said the basin’s entire system of water use needs an overhaul, and no sector should be let off the hook.

“Everyone needs to make a significant contribution to this problem. This is shared sacrifice from the get-go,” said Udall, a Colorado State University water and climate research scientist.

Trying to avert “a disaster”

Fueling these concerns is the dire five-year forecast made by the bureau for the river’s reservoirs.

In late September, the bureau found a 34% chance that by 2023, Lake Powell could fall below 3,490 feet, at which point Glen Canyon Dam could no longer generate electricity.

By the end of 2026, Lake Mead has a 41% chance of falling below 1,025 feet, which many water experts believe would pose a serious risk to its future and would invite federal intervention.

The "bath tub rings" around Lake Mead at the Hoover Dam in Boulder City, Nevada, seen here in August, show how far the water level has dropped. The Bureau of Reclamation declared a shortage on the Colorado River as the nation"s largest reservoir fell to 35% of capacity.

The bureau forecast also shows a very slim but not unthinkable possibility of both lakes falling by the end of 2026 to levels approaching “dead pool,” at which no water could be extracted.

“The United States and the states are not going to allow Lake Mead to go into dead pool,” said Central Arizona Project General Manager Ted Cooke on a recent webcast on the river sponsored by the Arizona Capitol Times newspaper. “That would truly be a disaster of many proportions. So how do you prevent it from doing that?”

Cooke and ADWR Director Tom Buschatzke have said states could require mandatory cuts beyond those in the 2019 drought plan. Or, they could choose less draconian measures, in which the states voluntarily agree to leave supplies in Lake Mead.

“Arizona’s goal is conservation and not greater cuts,” Buschatzke testified at an Oct. 6 U.S. Senate subcommittee hearing on Colorado River issues. He said the reductions should be achieved through “tribal and nontribal partnerships” and extensive collaboration.

Besides providing Lower Basin users financial incentives to save water, “we can see if the Bureau of Reclamation can do something to tighten up operations on the border,” California’s Hasencamp said.

“There’s still a lot of water being lost from the river system across the border,” whose rights are owned by various Lower Basin users but don’t get used in the U.S., he said.

How soon conservation can be carried out depends on the projects that are pursued. A fallowing program approved this summer for the Palo Verde Irrigation District near Blythe, California, for instance, can be done quickly, he said, because it had already received its environmental clearances for fallowing done in past years.

Colorado River water irrigates a farm field in Blythe, California on Sept. 7, 2021.

But for new conservation programs, more time would be required while the parties get environmental compliances and negotiate other agreements, he said.

Target numbers are evolving

This goal for quick savings stems from computer modeling that found that to keep Mead from falling below 1,020 feet, 500,000 to 750,000 acre-feet in reductions are needed, Hasencamp said.

“I can’t stress enough that the plan is evolving quickly and I really don’t know where we will end up,” he said.

Bronson Mack, a Southern Nevada Water Authority spokesman, confirmed “500,000 acre-feet seems to be a reasonable goal, but more is always better.”

Arizona Department of Water Resources spokeswoman Shauna Evans declined comment because “we are currently undergoing a sensitive and ongoing negotiation process.”

Hasencamp cited the conservation program approved over the summer for the Palo Verde District as an example of what officials want done on a larger scale.

Acres of land are left unplanted on a farm in Casa Grande, Ariz., Thursday, July 22, 2021. The Colorado River has been a go-to source of water for cities, tribes and farmers in the U.S. West for decades. But climate change, drought and increased demand are taking a toll. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation is expected to declare the first-ever mandatory cuts from the river for 2022.

Arizona, California and Nevada water agencies and the Bureau of Reclamation agreed to pay the district $38 million to fallow up to 20% of their land over three years.

How much more can be done depends on how much money the states have and how much the federal government will put in, Hasencamp said.

“That’s the easiest way to pay farmers to conserve water, either to fallow land or to pay for increased system water efficiency,” he said.

Buschatzke, the ADWR director, recently told Cronkite News that one option would be to use a drought mitigation fund authorized by the Arizona Legislature as an incentive, paying farms and other entities to voluntarily reduce their water use so more can be left in the lake.

Snowpack water soaked into ground

Buschatzke’s comments to the Senate subcommittee clearly linked the river’s diminishing flows to climate change. Many scientists have said that already based on peer-reviewed research. But it was one of the first times the director has spoken so directly and publicly on climate change impacts on the Colorado.

Acknowledging the overallocation of the river’s water supply and the existing, long-term drought as factors in the river’s woes, he testified in writing, “More importantly, many scientists believe that it is climate change, not drought, that is the root cause of declining flows in the Colorado River system.”

At the hearing, subcommittee chair Sen. Mark Kelly of Arizona asked Buschatzke to explain the past year’s river flows of 33% of normal — when winter snowpack reached 89%.

“We believe it is a prime example of what climate change is doing. It is hotter. It is drier,” Buschatzke replied, calling this phenomenon “something of huge concern to us.”

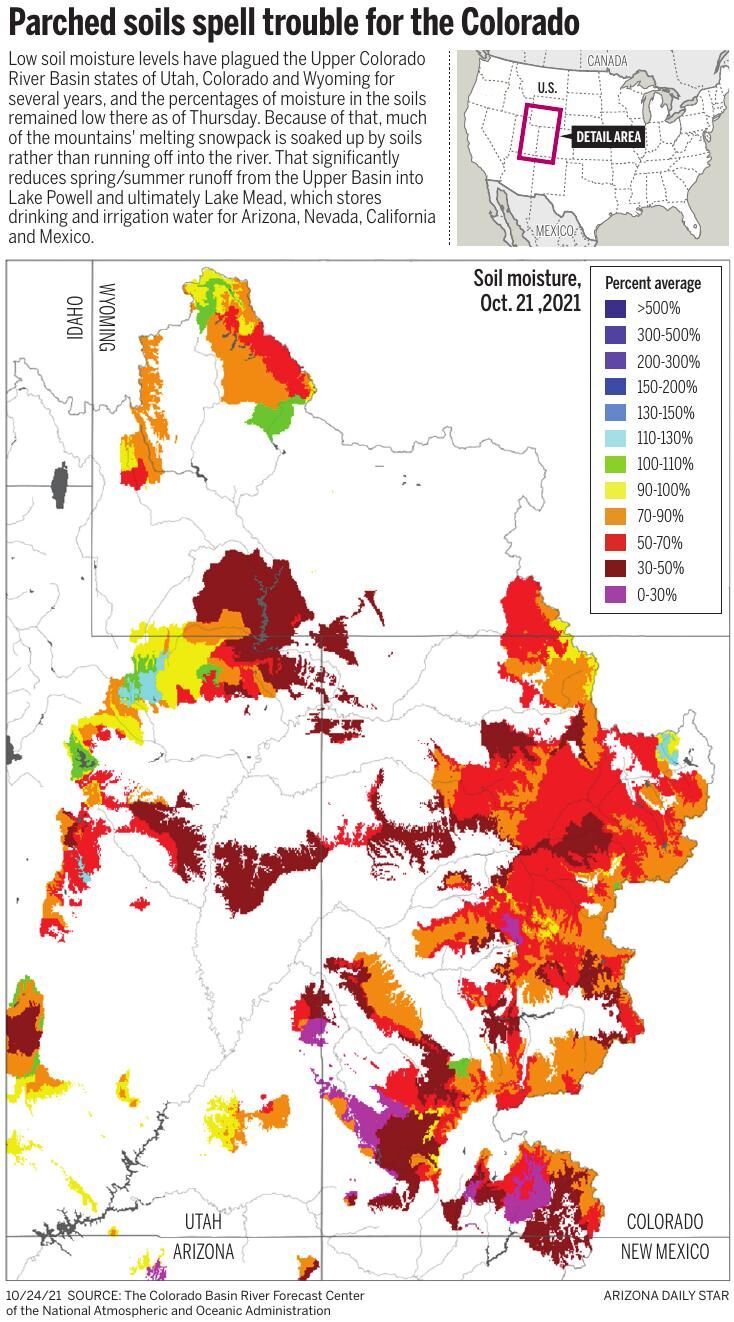

The prior year was a “nonsoon,” he said, referring to 2020’s near-record low summer monsoon rains. “We had very little precipitation. So the watershed was very dry. The soils were very dry … and a lot of the water just soaked into the ground.”

The Colorado River churns through the Palo Verde Diversion Dam near Blythe, California on Sept. 7, 2021. Some river water is channeled from the dam to local farm fields.

Farms versus cities?

Where will the savings start?

For the long term, “I don’t know how you get to 3 million acre-feet without an extremely significant contribution from agriculture, and that’s going to be very controversial,” said Sorensen, research director at ASU’s Kyl Center for Water Policy.

“Everyone has to play a part. It’s not to say the cities should not do more either, or mines, or all of us. But if the farms are 70% of water use, they need to be a significant part of the solution,” said Sorensen. She added that the cuts need to be done with sensitivity to rural communities that will be affected.

But farmers and agricultural interest groups have long felt a “target on our backs.” They see urban interests as wanting their water not to save lakes Mead and Powell, but to insure they can keep sprawling to urban fringes.

Robert Glennon, a University of Arizona law professor and a longtime writer on water issues, strongly advocates that cities and states pay farmers “a bunch of money” to switch to water-saving drip irrigation from center pivots and flood irrigation.

“It’s very expensive, way beyond the means of many farmers. It doesn’t mean you don’t do it. You subsidize it. You’re paying them to grow as much product as before, with slightly less water — a win-win,” he said.

The only immediate fix to the river’s crisis is to reduce farms’ water use at least 20%, said Brian Richter, leader of a national conservation group called Sustainable Waters.

Over the next five years, farmers should get financial incentives to fallow some of their land, to “save a lot of water in a hurry,” he said. Over five to 10 years, “we need to pay farmers” to shift to less water-intensive crops, or to permanently retire the least productive farmland, Richter added.

“There’s great opportunities to go to crops that use less water and still make the same level of revenue. Transitions are difficult for them, but I think they need financial help to get through that transition,” he said. “The other thing that they need is time. That is really difficult with the emergent crisis on the river.”

“Wrong approach,” says farm group

A group calling itself the Yuma Agricultural Water Coalition pushes back on that rhetoric. It wrote to Kelly’s subcommittee this month that recent news coverage is promoting a narrative that the river’s crisis warrants “reflexive reductions to agricultural water use in order to reserve more water for cities and the environment. That is the wrong approach and the wrong solution.

“Instead, the urgent situation we currently face elevates the importance of water users coming together to get through the immediate crisis, and rejecting the kind of zero-sum solutions that will come if we allow agriculture to be pitted against other water users,” the coalition wrote.

Agriculture contributes nearly $3.4 billion in annual economic activity to Yuma County, the group said. Its water use taken directly from the river amounts to more than half the CAP’s annual supply.

Yuma County is the third largest vegetable growing county in the U.S., producing 90% of all leafy vegetables nationally from November to March, the coalition said.

The Central Arizona Project canal, located near the intersection of Sandario Road and Mile Wide Road west of Tucson, Ariz., in Avra Valley. _Photo taken on March 17, 2021.

Across the California border in the Imperial Valley, the Imperial Irrigation District controls 2.6 million acre-feet, the biggest pot of water in the seven-state river basin, and more than one-third of the Lower Basin’s total share.

District officials sold off a half-million acre-feet of water rights to San Diego in 2003. They say they’ll conserve no more until getting assurances that the California and U.S. governments will act to restore the bedraggled Salton Sea.

The sea’s water is irrigation runoff water from Imperial farms, and the drop-off in such flows since 2003 has lowered the sea’s water levels, allowing more dust that’s toxic from agricultural chemicals to spew into the air, district officials say.

In addition, the district is hamstrung, it says, by a state water rights system that requires most water it conserves to be transferred to users with lower priorities, including Southern California urban water interests represented by the Metropolitan Water District. That allows the district to leave only a small amount in Lake Mead.

That provision was inserted into California water priority rules decades ago as a “quid pro quo” for Imperial garnering such a huge water allocation, said retired Metropolitan district general manager Jeffrey Kightlinger.

“Where is the incentive for conservation if we’re going to be penalized for doing a good thing?” said J.B. Hamby, a district board member.

But Wade Noble, a lawyer who represents four districts in the Yuma coalition, said attitudes among growers in that area have changed recently due to the declaration of a CAP shortage for 2022 and the sharp decline in reservoir levels since 2019.

“They are taking more of an attitude that it’s pretty obvious something has to be done,” Noble said.

Until now, “there was always optimism that the drought would ameliorate through precipitation, most hopefully snow. But this year was a real cruncher,” Noble said.

The "bath tub rings" around Lake Mead at the Hoover Dam in Boulder City, Nevada, seen here in August, show how far the water level has dropped. The Bureau of Reclamation declared a shortage on the Colorado River as the nation"s largest reservoir fell to 35% of capacity.

How much more should cities conserve?

As for cities, urban residents won’t have to save nearly as much water as farms, said Richter and Sarah Porter, director of the Kyl Center. That’s because cities have significantly reduced water use already.

In a study that Richter says is nearing publication, he and other researchers found that while the entire basin’s urban populations have grown 30% since 2000, their water use has dropped about 25%. The other basin states are Colorado, Wyoming, Utah and New Mexico.

“The cities are all doing a very, very good job on reducing their water use by conservation and finding other sources of water,” Richter said. “There’s still some room for them to do better. But I don’t see that as the challenge.”

In Tucson, however, a leader of a water conservation and resiliency group says the city — despite years of water savings — can still save plenty more by managing local supplies more efficiently.

Expanded water harvesting and use of “green infrastructure” such as native tree planting, among other tactics, can make Tucson and other cities far less dependent on imported supplies, such as CAP canal water from the Colorado, said Catlow Shipek. He is the policy and technical director of the Watershed Management Group.

In a recent op-ed in the Star, Shipek and two co-authors advocated for retrofitting existing homes and designing new ones to more fully use gray water, rain water and heavily treated wastewater in place of potable water. The article endorsed adding water conservation, water harvesting and reuse requirements for new development.

“We can fully support native plant rain gardens through harvested rainwater, nourish our vegetables from rain tanks and modify our patterns of water use indoors — which on a mass scale, could cut Tucson’s water demand in half,” said the article, co-authored by builder Dante Archangeli and Courtney Crosson, an assistant professor at the University of Arizona’s College of Architecture, Planning and Landscape Architecture.

“It doesn’t have to come down to people versus farms,” Shipek said. “That’s a disparity that people have talked a lot about. I don’t think it needs to be a reality.”