After more than a decade of preparation and several years of analyzing massive amounts of data, researchers announced the first results from the Event Horizon Telescope array in what could be an important step in solving the mystery of black holes.

The EHT is not one telescope, but rather a connected network of eight radio telescopes around the world — including two involving the UA — that synchronized together to make one huge virtual telescope.

The collaborative goal resulted in the first photograph of a black hole, researchers said.

Researchers on Wednesday released the first image of a black hole, which came from a galaxy 55-million light years from Earth. A researcher from the UA and a graduate of the university were part of the news conference in Washington, D.C. Other news conferences will be held Wednesday around the globe.

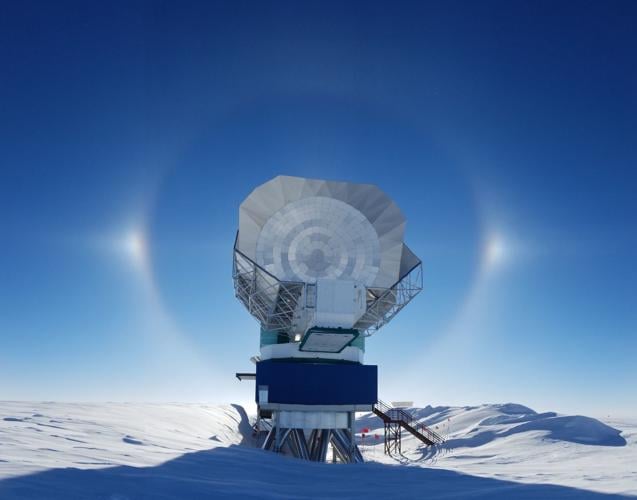

Two of the eight telescopes used in the 2017 data collection effort were integrated into the project by the University of Arizona: the Submillimeter Telescope on Mount Graham and the South Pole Telescope in Antarctica. Kitt Peak National Observatory, southwest of Tucson, will join the EHT project in upcoming experiments, along with a few more international telescopes.

The combining of eight telescopes around the world gave researchers the resolution needed to make the photographs — something that would not have been possible 10 years ago.

Before now, the feat of photographing something over 55-million light years away would be like "taking a picture of a doughnut placed on the surface of the moon," said EHT Project Scientist Dimitrios Psaltis, a professor of astronomy and physics at the University of Arizona.

The EHT will allow the scientists working on it to make a distinctive contribution to the field of astronomy, according to Dan Marrone, a UA associate professor of astronomy.

Marrone is the principal investigator for the EHT project at the South Pole Telescope, which is run by the University of Chicago in a wide collaboration with other institutions including the UA. He also coordinates a modeling and analysis working group, and is on the EHT science council, a group of 10 senior scientists who oversee the telescope project.

“We don’t have other ways to image black holes, so in that sense we are able to contribute something completely different than everybody else,” Marrone said. “There are a lot of mysteries about black holes that we have not been able to resolve without directly looking at them.”

Marrone said the telescope array does not run continuously, but rather does experiments of specific lengths. The first experiment was in 2017, and that large amount of data is what they are now sharing.

"The observations were a coordinated dance in which we simultaneously pointed our telescopes in a carefully planned sequence," Marrone said in a news release.

The groundwork for that first experiment was put in place 12 years before it happened. Marrone said the project started to gain steam in 2010, after several grants allowed the EHT team to make necessary improvements on several telescopes.

UA Astronomy Professor Feryal Ozel is a lead researcher for one of the modeling and analysis working groups that interprets the data from the EHT and is also on the EHT science council.

She said the research could have a big impact on the way people understand black holes.

“It’s a new and novel way of studying black holes that has not been possible before through direct imaging. It allows us to access information on spatial scale that has not been accessible before,” Ozel said.

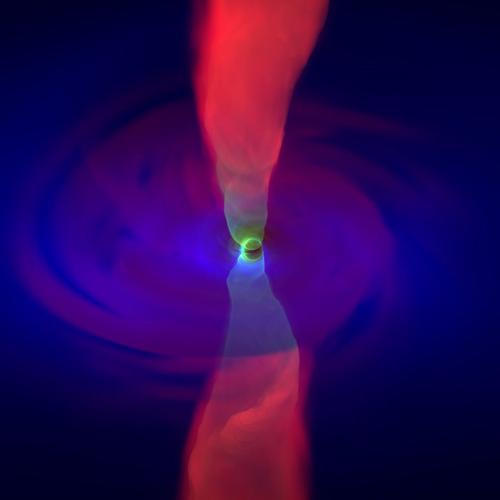

One goal of the EHT is to test Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity, which Ozel said suggests gravity comes from objects bending space and time.

“It’s Einstein’s geometrical description that all objects bend the space and time around them, and that black holes are these extreme objects that warp space time in a way that doesn’t allow matter or even light to escape from the innermost regions,” Ozel said.

An image of a black hole could help test that theory because, according to the theory, there should be a brightness depression at the center of an image of a black hole. This shadow can be measured using the photo, Ozel said, and then they can see if the measurements match up.

“If you know the black-hole mass, I can tell you exactly how big in the sky the shadow should look. So beyond obtaining images of black holes, we are able to ask ourselves ‘is there a shadow? Is that shadow the size that general relativity predicts? Is it the shape that general relativity predicts?’” Ozel said.

Black holes are the perfect environment to test the theory, Ozel said, because they’re so extreme.

“We expect any possible deviation from general relativity, something that may make us think that the theory is incomplete, to potentially manifest in black-hole environments and maybe become visible in black-hole images,” Ozel said.

Ozel and Marrone said they’re pleased to be contributing so much to the field, and as they’re at a research university, they also get to share the experience with students. The UA has 36 people working on the project, including undergraduates, graduates and postdoctoral students.

“We are extremely happy to have played a big role in this, and to be training a whole generation of scientists in this field,” Ozel said.